The Golden Era of San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 1930s-60s conjures images of old Hollywood and boozy bars, when the neighborhood had the largest concentration of Chinese-owned nightclubs (opens in new tab) in the country and one of the biggest Chinese populations outside of Asia.

With names like the Forbidden City, the Chinese Sky Room and Club Mandalay, the clubs served tourists and San Francisco natives alike with a taste of China tempered with American culture: Think steak-and-potato dinners prepared alongside pagodas, with performers marketed as the “Chinese Frank Sinatra” or the “Chinese Ginger Rogers.”

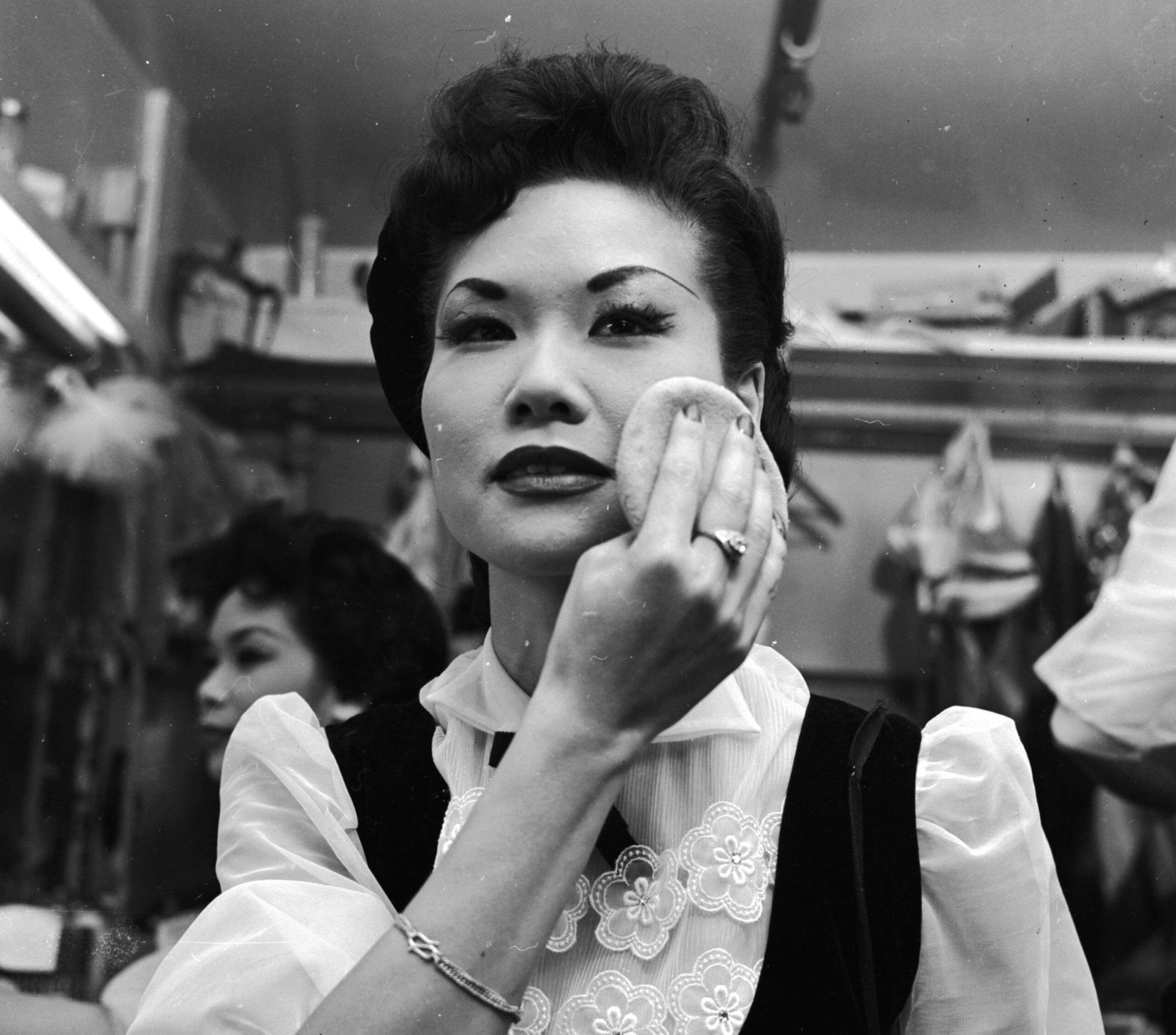

Chinatown produced its own stars (with their own names) like Jadin Wong and Jade Ling, and stars visited Chinatown, Hollywood celebrities like Rita Hayworth and Humphrey Bogart. “ABCs”—or American Born Chinese—defied the propriety of their Chinese-born parents (“CBAs”) to perform onstage in revealing, glamorous gowns made from sequins and feathers.

“It was shocking for the Chinese community and confusing to the Caucasian people,” said Frances Chun, who performed as a singer at San Francisco’s storied Forbidden City.

With World War II looming, GIs stationed in San Francisco had spare money to spend on live entertainment, and Chinatown clubs—in particular the Forbidden City—surged. Yet numerous factors, including cultural shifts and changing entertainment laws, led to the eventual decline of the once-thriving nightlife scene.

Fast forward to today, and the news coming out of Chinatown often appears bleak. The impact of the pandemic, the scourge of anti-Asian hate and concerns about mental health have shaken the Asian American community both nationally and locally.

But there’s another story to tell.

San Francisco’s Chinatown is on the brink of a cultural renaissance, one that leverages its storied past to tell a fuller story—with more authenticity and less romanticization—of what the neighborhood is all about.

Chinatown is looking ahead to the redevelopment of Portsmouth Square (opens in new tab), lovingly referred to as “Chinatown’s living room.” It’s celebrating the opening of the Rose Pak subway station, a transit connection decades in the making. New gallery spaces are thriving. And multiple nightclubs have recently opened for business, despite lingering pandemic uncertainties.

For Malcolm Yeung, executive director of the Chinatown Community Development Center (opens in new tab), a key part of this rejuvenation is reimagining Chinatown as a place of experiences, instead of a tourist destination for picking up $2 fans or plastic keychains. These experiences—which range from dining to drinking, art-gazing to live entertainment—lean on Chinatown’s colorful history to usher in a new Golden Era.

There couldn’t be a more appropriate time for it. The year of the Water Rabbit is about fluidity and being able to adjust quickly, according to Yeung—and there won’t be another one for 48 years.

“This year is about finding our way,” he said.

Reimagining the Golden Era

When Steven Lee moved to San Francisco from Vacaville in 1976, he never imagined he’d become an integral piece of Chinatown’s resuscitation. As a student at San Francisco State University, he just wanted to get his bachelor’s degree in broadcasting and party with his friends.

But soon he found himself hosting events, which turned into a career in the nightclub industry and ultimately led him to a stint serving on the San Francisco Entertainment Commission.

Yet it’s Lee’s role in preserving Chinatown’s heritage that will likely be his most lasting contribution. The former entertainment commissioner both opened the Lion’s Den nightclub (opens in new tab) on Wentworth Place and saved Sam Wo Restaurant (opens in new tab) from extinction.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of Sam Wo in the community—a place for locals and tourists alike, where some customers learned how to use chopsticks and everyone endured “the world’s rudest waiter,” Edsel Ford Fong, who made Seinfeld’s Soup Nazi look like a guardian angel.

In the ’70s and ’80s, according to Lee, all the restaurants were open until 4 a.m., and many people came to the neighborhood specifically to eat.

“Chinatown was booming,” he said.

But changes to parking ordinances, which made street cleaning at 2 a.m., hurt Sam Wo and many other area eateries that thrived on late-night crowds coming out from clubs.

“You’d come for $5 chow mein, but leave with a $60 parking ticket,” Lee said.

But it wasn’t the parking that ultimately did Sam Wo in—it was the health department, which closed down the famed eatery in 2012 due to numerous health violations. Lee became the hero, finding a new space for the eatery on Clay Street and trademarking the name.

While Sam Wo has historic photos of its more than 100-year run on its upper floor, the Lion’s Den enshrines Chinatown’s storied history even more.

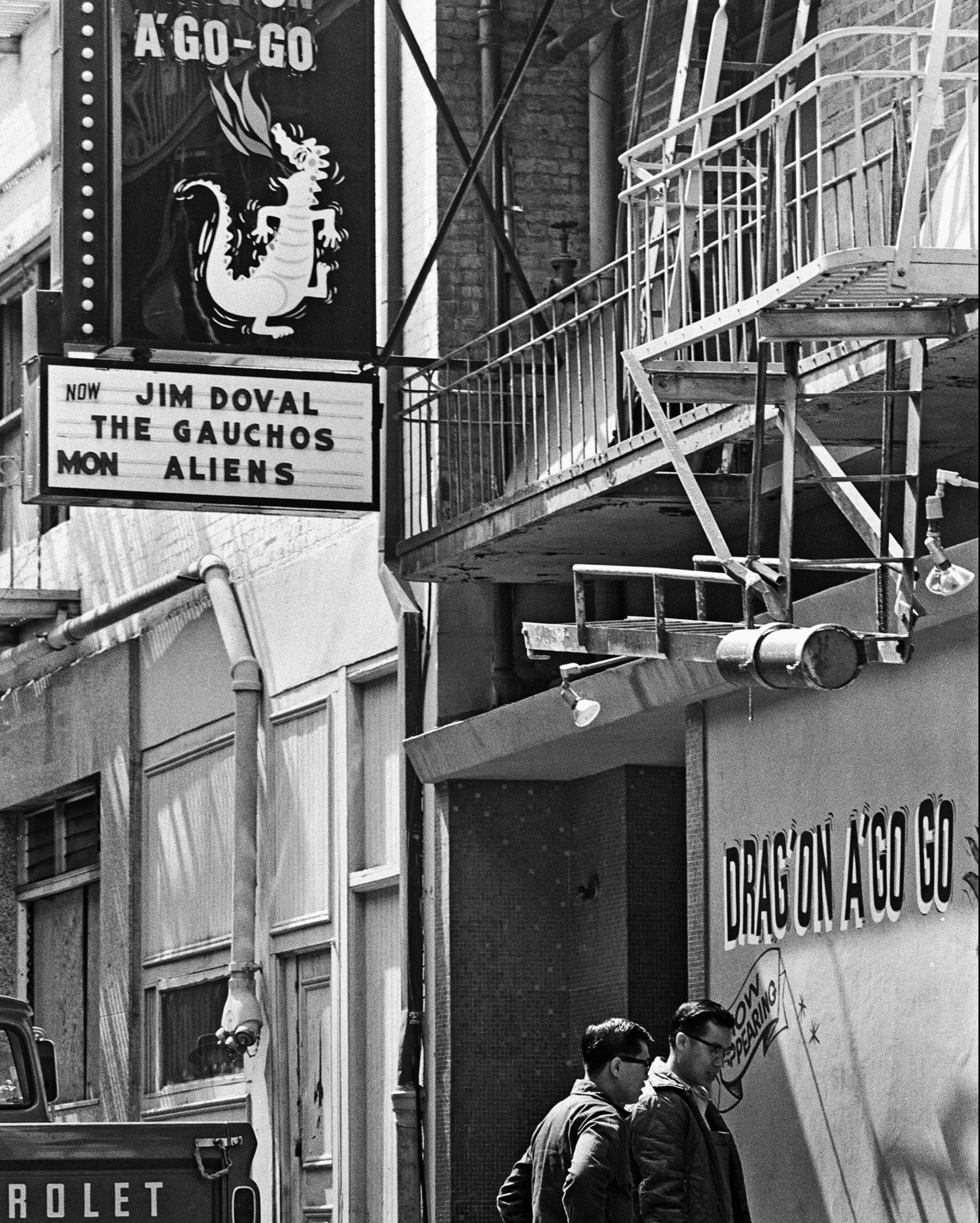

When Lee opened the club in 2021, he decorated the walls with black-and-white photos: Forbidden City owner Charlie Low with a young Ronald Reagan; Chinese Sky Room owner Andy Wong; a chorus of Chinese girls with Frank Sinatra, who is earnestly gripping an outstretched shin. The space itself is a nod to history—a club called Lion’s Den operated in the same spot in the 1950s before it became Drag’on A’Go Go in the 1960s.

Lee also proudly displays memorabilia from Flower Drum Song, one of his favorite movies. Its plot highlights the friction of generational conflict—and a nightclub owner—with San Francisco’s Forbidden City as its inspiration. The 1957 novel by C. Y. Lee was made into a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical in 1958 and a movie in 1961.

“It’s a modern club with a touch of culture,” Lee said of the Lion’s Den. The club has an entry room with seating for casual conversation as well as a performance space set up like a supper club from a classic movie—a stage with dining tables and banquettes surrounding. There’s also a members-only room for privacy and personal bottles.

Lee’s is the first new club to open in Chinatown in decades. Entertainment restrictions passed in 1986 forbade live music after 10 p.m., a regulation passed out of fear that the neighborhood would become a red-light district. The move ultimately stymied the development of the nightlife scene until it was lifted during the pandemic.

The club has no cover but often has live music—on the night I visited, a Frank Sinatra impersonator was crooning to a large and diverse crowd.

“Sixty percent of my clientele is white,” Lee said. “I can’t rely on one nationality to fund me.”

In the meantime, the resurgence of a nightlife scene has been bubbling, one that relies heavily on speakeasy vibes.

Around the corner from Lion’s Den, the otherworldly and celestial-themed Moongate Lounge (opens in new tab) opened in 2019 above Mr. Jiu’s restaurant, full of red velvet booths and soft lighting. Derrick Li opened the Blind Pig (opens in new tab) filled with comfortable circular booths and an inventive cocktail menu, with Li hoping to bring in live music and dancing.

There’s also the old standbys, the Buddha Lounge and the Li Po Lounge, which Lee calls “yuppie bars” but most people term dives. Both are legacy bars in their own right (opens in new tab), and the Li Po lounge looks exactly as it did in the Golden Era.

The only thing missing now in Chinatown, according to a couple hanging out at the Blind Pig’s horseshoe-shaped bar on a Thursday night? Those late-night eats.

Empress Yee

Some of the dancers from the Golden Era of Chinatown who grace the walls of the Lion’s Den are still around today—and they’re still dancing.

Cynthia Yee, a former beauty queen who danced at the Chinese Sky Room, founded her own dance troupe, the Grant Avenue Follies, to continue the legacy of those days.

Billed as “San Francisco Chinatown’s Nostalgic Nightclub Cabaret,” the group originally had four members from the Golden Era, though two have since passed away. The Follies regularly perform at venues across the Bay Area.

The group borrows from history, but it isn’t stuck in the past. They’ve risen and responded to the times. When anti-Asian hate surged in 2020 during the outbreak of the pandemic, the Follies sought to mount its own response.

“Clara Hsu, executive director of the Clarion Performing Arts Center (opens in new tab), and I were having dinner together,” Yee remembered. “I said, ‘What could we do as the elders? We are entertainers. What can we come up with?’”

It was Hsu who reminded Yee of the gai mou sou, or feather duster.

“Grandma would dust the furniture, but she’d also turn the duster around, and that’s how she would always warn the children, ‘You better mind, otherwise you’re gonna get a little pink bottom,’” Yee said.

The group’s “Gai Mou Sou Rap”—in which the members of the Grant Avenue Follies wear black shirts that say “Unity” and warn against bullying with feather dusters in their hands—went viral (opens in new tab). The clip is nearing 100,000 views on YouTube.

But not all its projects have a serious message. At a December rehearsal for a holiday show, Yee and her fellow performers danced with bells on their wrists to a song about Christmas in Hawaii, “from the land where the palm trees sway.”

Glamor also plays an important role. The Follies’ original costume designer was Chuck Gee, a designer from the days of the Chinese Sky Room and Forbidden City.

“We love bling,” Yee said with a laugh, a fact made apparent by the Showgirl Magic Museum (opens in new tab) that highlights the dancers’ storied past as stage legends—when the Clarion Performing Arts Center had to shut down because of the pandemic, Yee turned lemons into lemonade by opening the archive of feathers and sequins.

Trina Robbins, a local author and comics artist, dedicated herself to collecting the stories of the many performers and nightclub operators for her book Forbidden City: The Golden Era of Chinese Nightclubs after meeting Yee at a tap dance class at the Harvey Milk Center.

“These women were very brave,” Robbins said. “In most cases their parents didn’t approve, but they wanted to do it and they did it.

“Plus, they were all absolute babes,” she added.

Artists as First Responders

When Chinatown hosted its first-ever contemporary arts festival, “Neon Was Never Brighter (opens in new tab),” at the Edge on the Square gallery last April, no one was sure how it would turn out. The neighborhood hadn’t framed itself as a destination for modern art, and the pandemic still cast its shadow.

It was a smash hit.

“Thousands and thousands of people came,” said Candace Huey, head curator of Edge on the Square.

“People waited for two hours to eat at restaurants,” Huey said.

“Asian Americans haven’t necessarily been seen in contemporary art spaces,” said Cynthia Huie, who co-founded the organization Art Walk SF (opens in new tab) to bring art to neighborhoods across San Francisco. “People think of Ming vases.”

“Being an artist is also often not looked upon as a viable career path in Asian families, where people are instead encouraged to be doctors and lawyers,” Huie said.

But all of that is changing, according to Huie, thanks to energizing and exciting art spaces like 41 Ross (opens in new tab) and Edge on the Square (opens in new tab), which are allowing Asian Americans to see themselves at the center of the art world, of newness, rather than on the fringes.

Yet Edge on the Square intentionally plays with liminality to speak to the Asian experience.

“Communities of color are often relegated to the edges,” Huey said. “And for art, it’s more interesting to look at what’s at the edge, in the margins.”

But that doesn’t mean that art is to play a fringe role in Chinatown’s revival—Edge on the Square, run by the Chinatown Media & Arts Collaborative (opens in new tab), occupies a space in the heart of the neighborhood, on the corner of Grant Avenue and Clay Street. The current, multi-sensory exhibition—that includes everything from photographs to installations to a bartering table—speaks to both the neighborhood’s history and its future.

There’s even a “Golden Age” mailbox—in gold, of course—where you can write letters to Chinatown that won’t be opened for 10 years.

“The regeneration of one neighborhood can have an impact on the whole city,” Huey said. “It’s about widening the aperture of human experience.”

Art, music, dance, drink—they all play an important role in the revitalization of a new Chinatown, one that honors the many complex layers of its history.

It’s all about the experience of Chinatown. But this time, the narrative will be wider, more inclusive, more Asian.

“It’s about telling the story of our community that highlights 170 years of literal creation and construction of the American West,” Yeung said.