In the early evening of April 22, 2006, Willie Allen was stabbed to death while leaving a corner store near the intersection of Hayes and Fillmore.

The San Francisco Police Department’s homicide detail opened a case, but it went cold. Two years later, the city offered a reward for $250,000 (opens in new tab) to help solve the killing. But it took years before someone came forward with a tip that cracked the case.

In 2013, the Board of Supervisors paid an unnamed person $250,000 for information that led to the conviction of Allen’s killer.

It’s the last such reward given, according to records from City Hall and SFPD, though the department continues to announce new cash bounties.

The dearth of payouts raises questions about the effectiveness of cash as a crime-solving tool. Meanwhile, the families of homicide victims don’t understand why some have rewards attached to their cases and others don’t, while the department doesn’t seem to know how much money it’s paid out or has in the bank.

Allen’s case was one of many unsolved slayings in San Francisco with rewards offered for their closure and one of 14 in which money helped solve a homicide.

In August, the department issued a press release announcing a $50,000 reward to solve the killing of two men at an Ingleside (opens in new tab) playground earlier this year. Then, in September, the department offered a $25,000 pot for information leading to the arrest and prosecution of those responsible for a 2021 killing (opens in new tab) at 25th Street and South Van Ness Avenue.

The SPFD’s website currently lists $1.7 million in rewards (opens in new tab) in 17 cases—but even older cases, going back at least two decades, offer cash bounties.

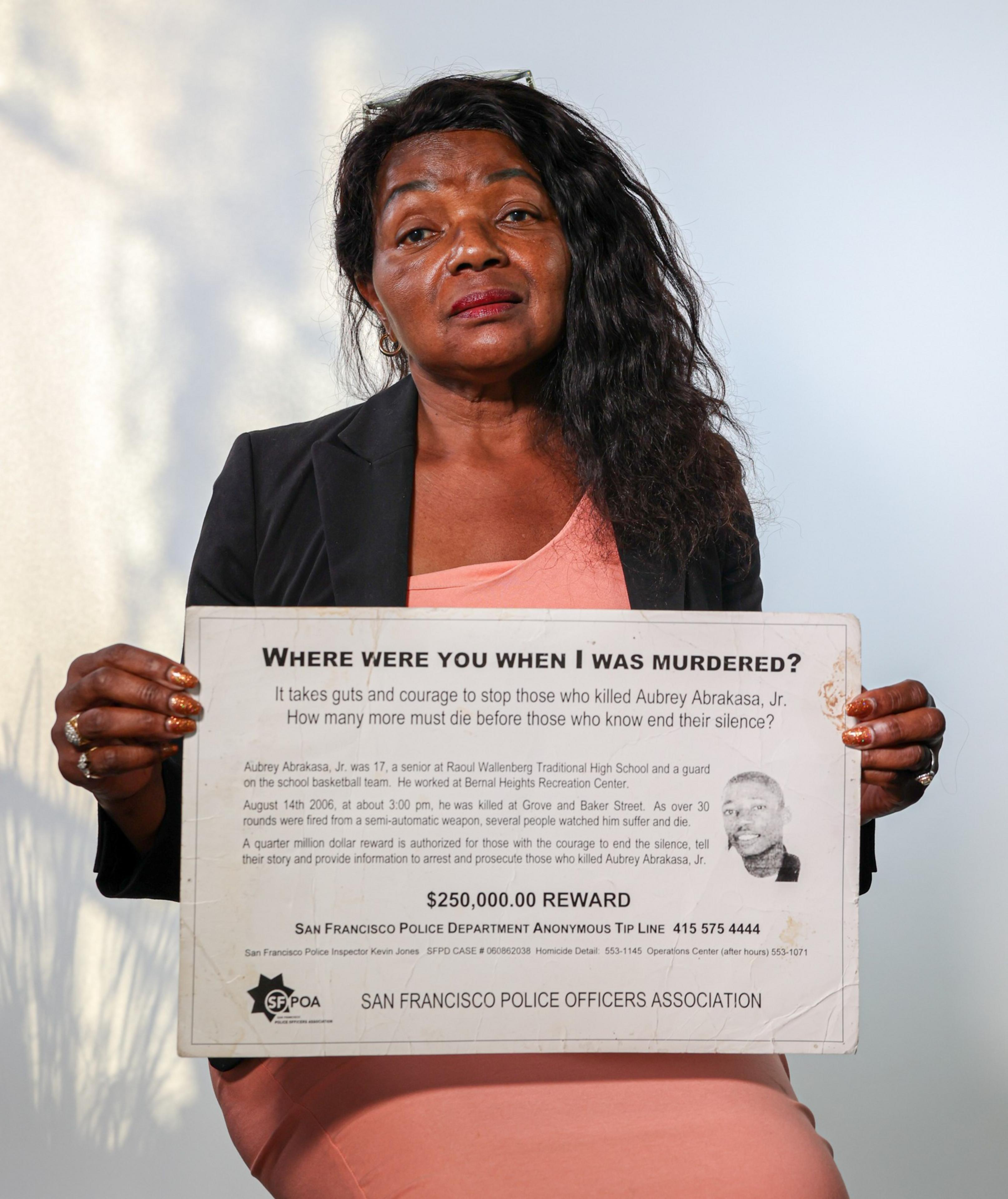

Paulette Brown, whose 17-year-old son Aubrey Abrakasa Jr. was killed in 2006, said the $250,000 reward hasn’t seemed to aid her son’s case.

“I am concerned,” Brown said. “It’s been 16 years, and this reward has not brought any justice to my son at all.”

No Reporting on Payouts

Despite the paucity of tipsters and information on rewards in the past decade, the city says it has a policy on the subject and streamlined process for paying unsolved homicide rewards—even if SFPD has failed to abide by them.

Six years ago, Mayor London Breed spearheaded the San Francisco Homicide Reward Fund (opens in new tab), which gives the police chief discretion over which cases get rewards, how much is paid and who gets to cash in. It requires the chief to get approval from the Board of Supervisors if the reward is over $100,000 and to report annually on how much was allocated from public agencies, how much came from private donations and how much of it was actually doled out for bounties.

But the department has failed to ever report to city leaders on those funds as required by law. It also doesn’t know why no tipsters have been paid since 2013.

SFPD spokesperson Robert Rueca said the department has no records of ever paying a reward, even if there is documentation showing payments were made nine years ago. The department also said it has no records of how much money it has in the bank for rewards and how that money has been managed.

“We do not have records that show that a reward has been given,” Rueca wrote in response to The Standard’s public records request.

When asked to explain the status of current funds, why the program seems to have garnered few tips and why the department has failed to report on its status to the city, Rueca did not respond.

But the department is not alone in its ignorance.

Most members of the SF Police Commission, which oversees the department, said they knew little about the reward funds or how they’re managed.

Commissioner Kevin Benedicto said he was surprised to learn how little has been paid out.

“I’d be interested to learn about that,” he told The Standard. “I’d hope there is some value in the existence of the reward.”

Former Police Commissioner Angela Chan, who served on the body from 2010 to 2014, had little knowledge of the rewards funds either, saying she doesn’t recall anyone getting a payout.

How It’s Supposed to Work

Before 2016, the city ran an ad hoc system that paid nearly $400,000 in 14 cases from 1999 to 2013. As of 2013, according to the then-mayor’s Budget Director Kate Howard, reward payments came out of the department’s budget for claims and judgments.

The patchwork system included numerous reward funds set up by the city, as well as others privately created but managed by the city. The setup gave the impression that homicides involving rich, white victims were privileged with higher rewards, said Paul Henderson, the head of the Department of Police Accountability.

What’s more, before a policy was written, the District Attorney’s Office and SFPD didn’t want to take responsibility because they were afraid they’d have to pay rewards out of their budget, Henderson said. Under former Mayor Ed Lee, Henderson, as deputy chief of staff, was tasked with fixing the issue.

“This was a big, messed-up program about the rewards,” Henderson said, “and everyone pointed their fingers.”

What emerged was a policy that said that anyone who wanted a reward is required to write a letter to the mayor’s office 60 days after a conviction. The case’s investigator then has to pen a memorandum to the mayor’s office recommending the claimant for reward. Rewards can only be given after SFPD and the District Attorney’s Office have confirmed the reward.

Neither city officials nor their families are allowed to receive rewards, neither are those who help a case as part of a plea bargain or settlement. People wanted by the law, or who turn over information so their criminal rivals go to jail, are also barred from collecting the payouts.

In 2016, the process was further clarified with the passage of the Homicide Reward Fund, which allowed SFPD to pay $250,000 to anyone who aids in the arrest and prosecution of a cold case. Any amount over $100,000 needs approval of the Board of Supervisors.

Despite the city’s efforts to create a clear process, the system’s lack of transparency can seem arbitrary. Some cases offer higher rewards, while others offer none at all.

Anna Oliver said she had to pressure the city and mayor to get a reward amount raised for her brother, Pierre Oliver.

“I think they’re better than nothing, but I feel like they don’t offer it [to everyone],” Oliver said.

SFPD homicide’s Lt. Kelvin Sanders said rewards are offered to all homicide cases after they have gone cold (opens in new tab), though each is assigned a different amount based on the details of the killing. If a case is gang-related, there is often more fear of retaliation for tips, so the rewards can be higher, Sanders explained.

The 2016 law said that choice of reward would be based on the “nature of the crime, the length and difficulty of the investigation and prosecution, and the usefulness of the information furnished by the person claiming the reward.”

But Kenya Tay, whose two brothers’ killings have not been solved, said her experience has been contradictory and confusing.

Tay said there had been a reward for the slaying of Tony McDougal, who was killed in 2007, but not her other brother, Eduardo Tay, killed in 2017.

Tay said that an inspector working on her young brother’s case told her that he didn’t want to put a reward out because it might scare away suspects. But after she voiced her concerns at a police commission meeting in June, that brother got a reward, too.

“I kinda feel like they’re doing it to shut the families up,” Tay said.

For David Calderon, whose mother Carmelita Hollbrooke was killed in 1992, there has never been a reward.

“They thought no one would care,” Calderon said.

Do Rewards Work?

When Breed’s legislation governing the current reward system for unsolved homicides was passed in 2016, she and the police department said that money can help solve crimes.

“My hope today is that we can solve murders, and in doing so, maybe we can prevent them,” Breed said in announcing the initiative, adding that in unsolved killings a reward can “make all the difference.”

The department echoed her positions then and now.

Then SFPD Commander Greg McEachern said money is one tool that can be used to help the department solve the hardest cases.

“While you would hope that an individual who has information on a homicide would come forward with that information just out of the sheer responsibility of a community member,” McEachern began, “I think we would be fooling ourselves if we thought that they aren’t in fear, and there are other aspects that would help with that information.”

Why the department has not paid any rewards since 2013 is unclear, said Sanders of the department’s homicide detail. He believes fear is a major factor governing the lack of tips, especially since it’s much harder to disappear in the digital age if the tipster wants to start a new life far away for fear of retribution if they do cooperate with police.

“People are scared, and they don’t want to come forward,” Sanders said.

Even so, he said he believes rewards are useful (opens in new tab).

The family members of the victims of unsolved homicides are less convinced of the efficacy of rewards—even if they may be better than nothing.

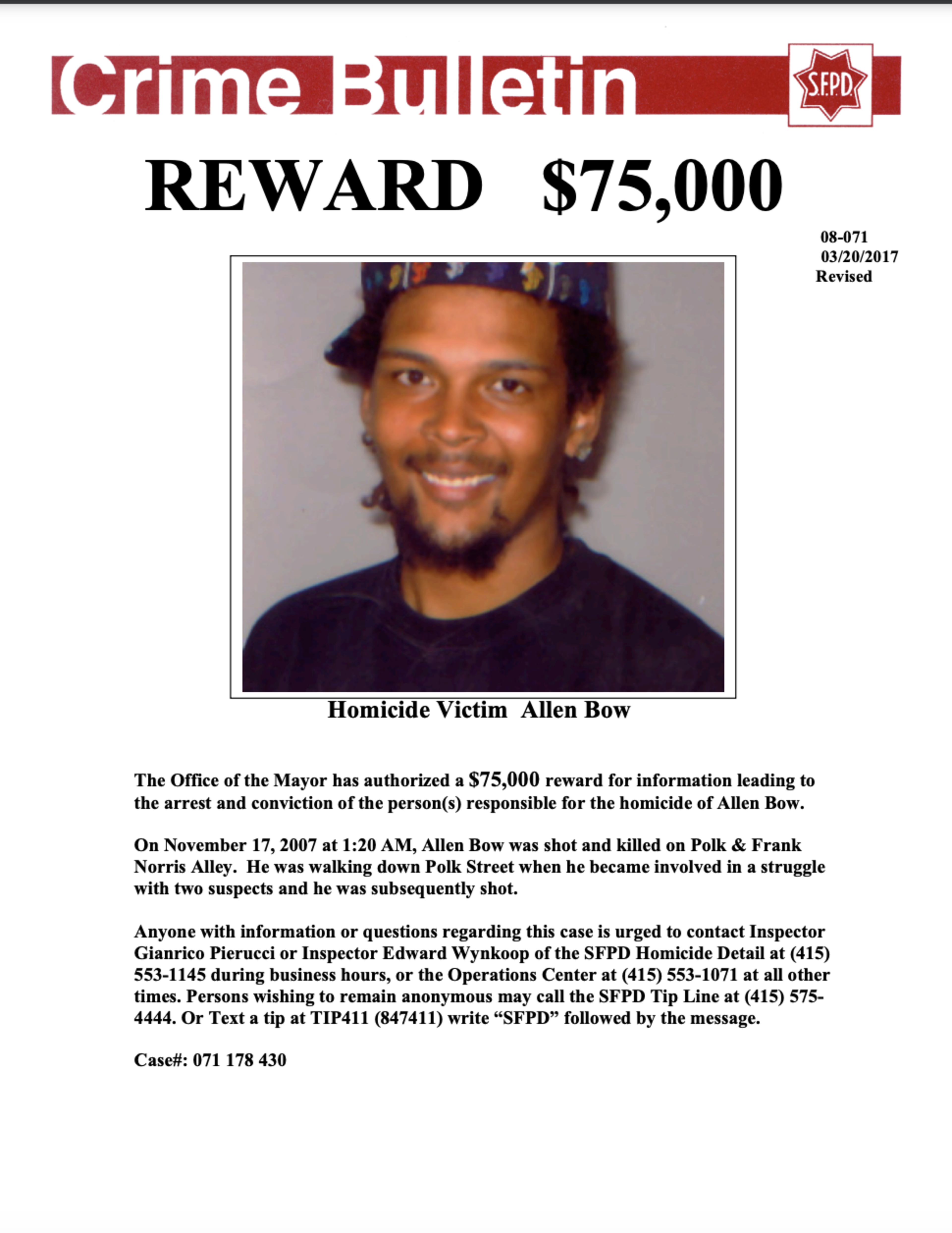

Retired Muni bus driver Mary Bow, whose son Allen Bow was killed nearly 15 years ago, said she doesn’t think the reward will make a difference.

“If you’re desperate, $10,000 is a lot of money,” she said, “but if you’re from the streets, it’s not worth it: $10,000 is not worth your life.”