Budget cutting can be vexing to even the strongest of school district leaders. It’s much easier to decide how to spend new money in schools than it is to decide what to cut.

But that’s the challenge now in front of the San Francisco Unified School District and many other California district leaders and school boards.

For the first time in over a decade of strong revenue growth, districts are facing deficits. Back in 2013, per the National Education Association, the average school-year expenditure in the Golden State was $9,051 per student (opens in new tab). Since then, the Legislature has steadily pumped more funding into schools. Then came federal Covid relief funds. Fast-forward to this year, and California schools are spending an average of over $18,000 per student (opens in new tab) per school year. That’s a 56% jump even after factoring in inflation.

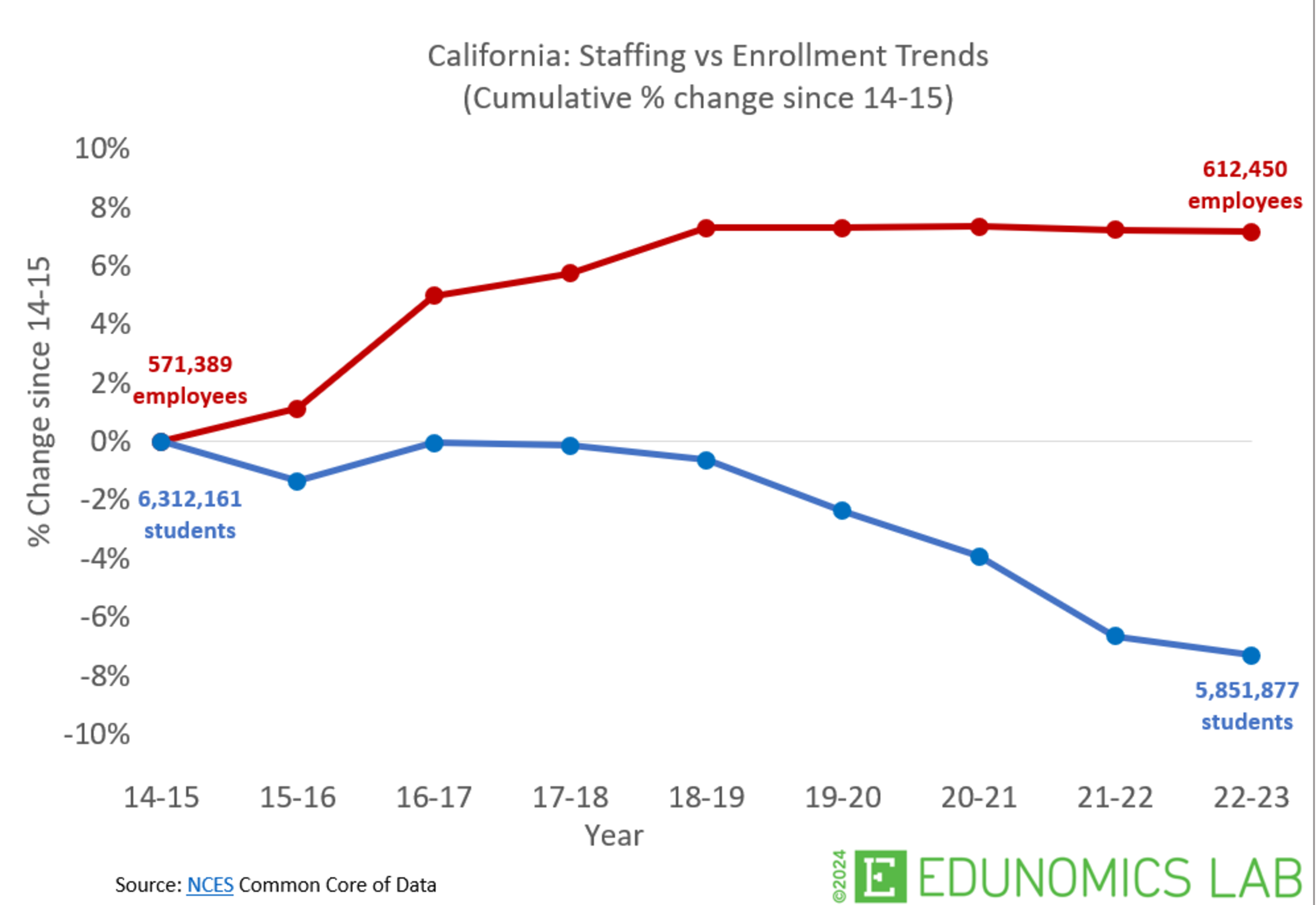

The boom times meant districts could add or maintain staff, even as they served fewer students. And they could award pay raises, which they did. California’s average annual teacher pay now sits at $95,160 (opens in new tab)—the highest in the nation.

But the boom era is stalling. Pandemic recovery funds are drying up, and state funds are tightening. Fewer students mean fewer dollars, leaving many districts with no choice but to reevaluate investments, downsize and likely reduce staffing.

Today’s leaders face the unenviable task of deciding which employees get pink slips, which programs to cut and which schools to close.

It’s the part of the job most leaders would rather avoid. Many do, kicking the can down the road for their successors to deal with. But avoidance only makes it worse.

Take SFUSD, where dire financial problems have been years in the making, according to a recent audit from the California Department of Education. The audit points to a laundry list of financial missteps: inadequate budget development and monitoring, one-time funds used for recurring labor commitments, unreliable financial data and a lack of financial awareness and capacity. The district faces a $421 million budget shortfall by 2025.

These warning signs went unaddressed for too long, necessitating deep destabilizing cuts all at once–or the very real risk of running out of cash next year.

Business as usual won’t suffice. SFUSD leaders, including the board members, should commit to weekly meetings to tackle these fiscal issues head-on. They’ll need time to identify schools for closure, reopen labor contracts, prioritize programs and services for elimination, and consider proposals for redesigned, financially viable schools that will maximize value for students.

SFUSD’s fiscal cliff is coming months ahead of many other California districts. Most peer districts still have some remaining state emergency block grant funds at play, so their financial pressures are just now starting to surface.

In that sense, the San Francisco audit should serve as a wake-up call to other districts, particularly those where leaders aren’t already engaged in the hard work of rightsizing their budgets.

For many, this will be their first budget-cutting rodeo. Done well, this work takes time and requires months of engagement with the community. (See for example how San Rafael’s superintendent kicked off a budget-cutting process with a helpful video (opens in new tab) back in January.)

The temptation will be to put off delivering bad news, but communities feel blindsided when deadlines force hurried decisions. (Final layoff notices are due May 15 in California, and each budget must be signed by June.) Take Fresno Unified, where a scramble to cut $30 million (opens in new tab) has leaders trying to hastily explain why they need to protect reserves and what the implications of the cuts will be for ethnic studies.

Inaccurate or missing financials aren’t unique to SFUSD. For several years, Berkeley’s expenditure (opens in new tab) reports indicated it spent some $60,000 per student. (Obviously, it didn’t. Those figures are way off.) Santa Cruz’s report (opens in new tab) shows it spent only about $5,000 per high schooler. (Also wrong.) Granted, these are numbers reported to the state (not used internally), but seeing the errors year after year should be a flag to district leaders that their financial reporting needs some work.

It’s also an indicator that in too many districts, those leaders aren’t properly prepared for the financial aspects of their roles.

Rarely do district administrators get training (opens in new tab) on the connections between budgets and student outcomes or what options exist when financial conditions change. And we’ve found that about half of school board members remain silent during budget deliberations (opens in new tab), save for perfunctory responses. (After years of fielding training requests and not finding a go-to source for such training, the Edunomics Lab has incorporated these elements into a certificate program (opens in new tab) now delivered all over the country.)

Strong financial leadership matters more now than ever. Budgets are tightening, and students still have a way to go to recover from pandemic-era learning losses. Our public education students need their leaders to get up to speed on the financial responsibilities associated with running a school district. As Michael Fine, CEO of California’s Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, lectured SFUSD leaders at a recent board meeting, “Ladies and Gentlemen, that’s your job.”

Marguerite Roza is director of Edunomics Lab at the McCourt School of Public Policy and a research professor at Georgetown University, where she leads the Certificate in Education Finance.

Maggie Cicco is a research fellow with Edunomics Lab.