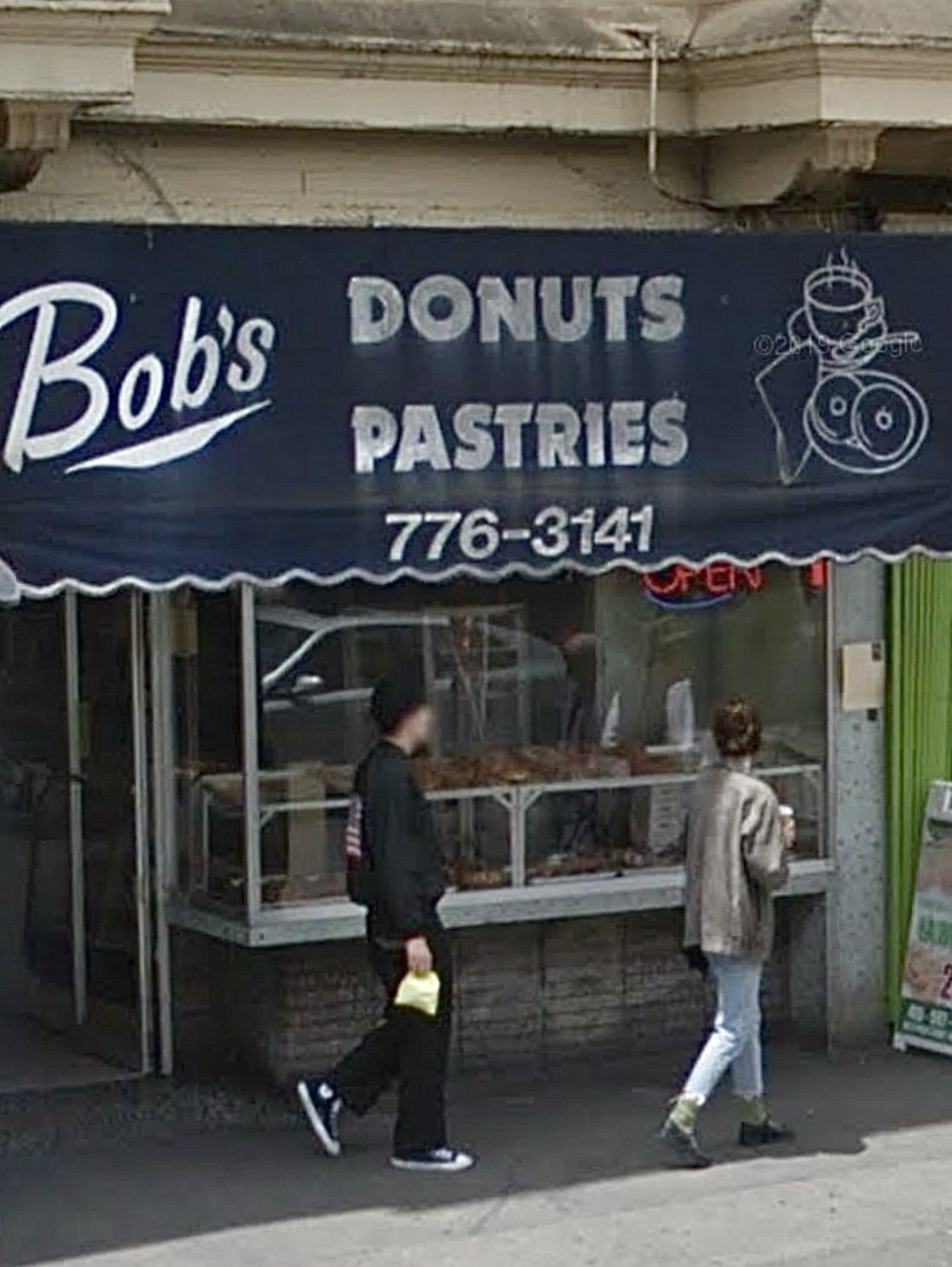

If you want to know how Aaron Peskin would run San Francisco if elected mayor this November, ask him about Bob’s Donuts.

I did just that on a stunning Saturday morning in late June, when the two of us sat down at an outdoor table at Caffe Trieste in North Beach. Peskin was in his element here, greeting passersby and their dogs, making chit chat with the regulars. Because we only had a short time together, I got him down to business quickly.

Why had Peskin, the Board of Supervisors president, mayoral candidate and leader of the city’s progressive wing, recently written and passed a bill (opens in new tab) that benefited a single business in his district: Bob’s Donuts?

Some background: The donut shop, owned by the Ahn family since 1977, wanted to expand this spring to a new location across Polk St. But they were prevented from relocating because of a law Peskin himself had written seven years ago. After hearing their pleas for assistance, Peskin decided to wave his legislative wand and introduced a new bill—with ultra-specific language that applied only to Bob’s Donuts—that would allow the shop to change addresses.

Peskin is known for not mincing words, so I decided not to either: This is a rotten way to govern, I suggested. Making one-off changes to the planning code to benefit a single donut shop is a recipe for dysfunction, the kind of bureaucratic sludge that has made it a mess to get anything done in this city. Surprisingly, even disarmingly, Peskin initially seemed to agree.

“It’s a rarity,” he allowed. “Legislation—whether it is land use or public health legislation or the public works code, you name it—on balance does what it is designed to do. But sometimes, it catches a couple of fish in its net that it wasn’t designed to catch. And then you’ve got to go in there by hand and get that porpoise out of the tuna net.”

But there are some funny things about Peskin’s fishing methods. When he passed the 2017 law that necessitated the new ordinance for Bob’s Donuts, Peskin was taking aim at other entities that he wanted to keep out of his backyard—namely national chains and other “formula retail.” However, the legislation was written so broadly it would inevitably affect other local businesses. Peskin claims innocence here, but savvy operator that he is, he had to know that there would be innocent bycatch.

Another thigh-slapper is Peskin’s assertion that maneuvers like these are an exception to the rule. In fact, he deploys them regularly, whether to benefit a single business (see his previous law-tweaking on behalf of Bi-Rite Market and El Farolito (opens in new tab)taqueria) or to opt his district out of citywide ordinances—as he did late last year when he insisted on an exemption for the historic areas of the Northern Waterfront from new, citywide building rules.

Because he is far better than any of his current colleagues at manipulating the levers of city government—hell, he might be the best ever, the GOAT—Peskin has set up a shadow planning process that puts one man in charge of deciding which businesses get to operate and which don’t in his corner of San Francisco. This, to me, is a troubling feature of Peskin’s style of leadership—and a warning to voters who would elect him mayor.

‘I don’t make unilateral decisions’

The specifics of how Peskin handles situations like the Bob’s Donuts Affair are worth studying.

The goal of his original 2017 legislation was to preserve the character of the Polk Street Neighborhood Commercial District by prohibiting storefront “mergers” and requiring special permits for businesses to exceed a certain size. The “net” was cast to keep out one of Peskin’s longtime bugaboos: chain stores. Peskin famously wants quaint neighborhoods in his district to stay the way they are. So he wrote bespoke regulation at odds with the city planning code to make it so.

The 2024 legislation, which doesn’t mention Bob’s by name, amends the planning code Peskin wrote seven years ago, “to create an exception to allow storefront mergers and large uses for certain Limited Restaurant Uses designated as Legacy Businesses.”

Though Bob’s has been around since the 1950s, it wasn’t officially designated a legacy business (opens in new tab) until June, when Peskin fast-tracked its application. Once Bob’s was deemed historic, it was allowed to pack up and move down the street. Simple, really.

Peskin sees his machinations not as evidence of his being a fickle neighborhood potentate, ruling from on high about every picayune planning permit, but as the epitome of “constituent service.” Indeed, the store’s general manager, Rebeka Ahn, whose parents own Bob’s, appeared at Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors committee hearings to thank Peskin profusely by name.

“I have long believed in neighbors and businesses having a modicum of say over the future of the neighborhoods where they live and work,” Peskin said to me over coffee. “I don’t make unilateral decisions on their behalf. I do it in consultation with them.”

However, Peskin’s detractors find such an explanation far-fetched, believing that he has worked these long years to position himself as the ultimate decider of planning matters both large and donut-hole small. I asked him what he makes of these critics and their objections.

For a moment, the voluble pol was speechless. He scrunched up his shoulders and contorted his face into a strained smile, which I read as a version of “Screw them!” I invited him to put words to his gesticulations, and what emerged was a finely distilled example of the Peskin Doctrine.

“Chatterers will chatter,” he began, but “listening to and working with and negotiating with your constituents is an effective form of democracy. Because I’ve been reelected by them five times. There’s my answer.”

Unsurprisingly, the city’s planning apparatchiks see things a bit differently.

In a dry but nevertheless scathing report (opens in new tab) on the proposed Bob’s Donuts legislation, the staff of the Planning Department reviewed the other instances Peskin has written special legislation to benefit one business in his district, including Bi-Rite’s move onto Polk Street and a similar provision for The Jug Shop, a liquor store.

Planning staffers recommended approving the Bob’s Donuts move, avowing that it prefers what San Francisco calls “fine-grained” retail over “formula” stores. But it also recommended removing the restrictions that forced Bob’s Donuts to seek out Peskin’s help in the first place.

“We need to make it simple for local businesses to open and thrive in our neighborhoods,” said Rich Hillis, the city’s director of planning, “which is why our recommendations would have allowed a small retailer or restaurant, such as Bob’s, to obtain permits over-the-counter.”

Sue Diamond, the chairwoman of the Planning Commission, is also for the Bob’s Donuts expansion–but against how it went down. As planners, she told me, it’s important to “make this about the uses we are approving, not the users. What I am not supportive of is that it only applies to Bob’s Donuts.”

Peskin’s response to Planning’s suggestions? He ignored them. The Board of Supervisors passed his legislation as written. When I asked what he thought of the recommendations by the city’s appointed planners, he had only a wan response. “We live in a complex city with different needs and different geographies and different communities. I don’t think that we live in a one-size-fits all world,” he said.

That is a perfectly sensible thing to say. However, it belies the fact that the city actually has two planning regimes: one for the people who live or run businesses in Peskin’s district, and one for the rest of us.

‘Anything you want, short of a bordello’

Last December, Mayor London Breed passed legislation that included more than 100 changes to the planning code, primarily to streamline permitting processes. It was barely reported at the time, and you have to dig deep into the legislation (opens in new tab)to find it, but one neighborhood received a blanket exemption from the changes: Peskin’s North Beach.

Peskin is unapologetic about this carveout, arguing that permitting in North Beach works just fine, thank you. “When the neighborhood is healthy and vibrant, you want to make sure what makes it healthy and vibrant is maintained. You don’t kill the goose that’s laying the golden egg.”

Or, to paraphrase a famous quip (opens in new tab) by another powerful politician, Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago, as far as Aaron Peskin is concerned, North Beach ain’t ready for reform.

Of course, Peskin believes that broad-brush planning tools are great for areas of the city that aren’t as spiffy as North Beach and his section of Polk Street. “When the mayor and I teamed up and passed a slew of land-use changes for downtown and Union Square, I said, ‘You can do pretty much anything you want, short of a bordello,’” he told me.

So what does all of this say about the prospects of Peskin replacing Breed as Mayor, which recent polls indicate is a distinct possibility? Certainly, it would mean having an able operator at the helm of a volatile city. You could envision a Peskin administration cutting through enormous amounts of red tape to approve housing and development in all parts of the city. Or you could see him applying his same style of capricious oversight to the entire 7×7, with every building and business permit in San Francisco requiring his own imprimatur or sleight of hand.

I ask him why he thought his colleagues didn’t avail themselves of the same parliamentary gamesmanship he does. “One is because they don’t spend all day Sunday reading every fucking word on the coming week’s agenda,” he said. “And the other is because they may not have had the amount of neighborhood contact that I’ve been able to develop over 25 years.”

But would a Mayor Peskin be capable of governing on behalf of the whole city rather than his charming section of it? After all, this kind of stubborn parochialism, if extended citywide, would see the city bending to the will of one man–whether or not it liked his views of what their neighborhoods should look like.

Peskin responds that he spends a mere 30% of his time on constituent matters. The rest of the time he’s collaborating with the mayor and other officials on matters that do affect the whole city. “I mostly am wrestling with, you name it, sea-level rise, deferred pension liability, rainy day reserves, the citywide budget, children, youth and their families.

“I consider myself to be a citywide supervisor,” he went on. “But if you have a constituent issue that comes from the 94108, 109, 111 or 133 ZIP codes, you’re my problem.”

In this regard, he likens himself to another San Francisco politician whose prowess at working the system may be one of the few to rival his: “I mean, Nancy Pelosi, her job is to [both] bring home the bacon and make national policy.”

Here’s one instance where I am inclined to agree with Peskin. Like Pelosi, Peskin has shown the ability to convince disparate lawmakers representing narrow-bore interests to work together to enact policies that are good for the whole. At his best, Peskin is capable of living up to these pluralist ideals.

That said, I can’t help but imagine the unsavory and undemocratic attributes of a Peskin Administration, where kissing the ring of a powerful man means more than due process and good governance.

Back at Bob’s Donuts, there was a line out the door on Polk Street on a recent morning. The shop plans to relocate across the street next year. Its owners are undoubtedly grateful to enjoy the patronage of Aaron Peskin, an insider able to help them navigate the complexities of City Hall. But you wonder if they realize that he’s the one who made life so complicated for them in the first place.