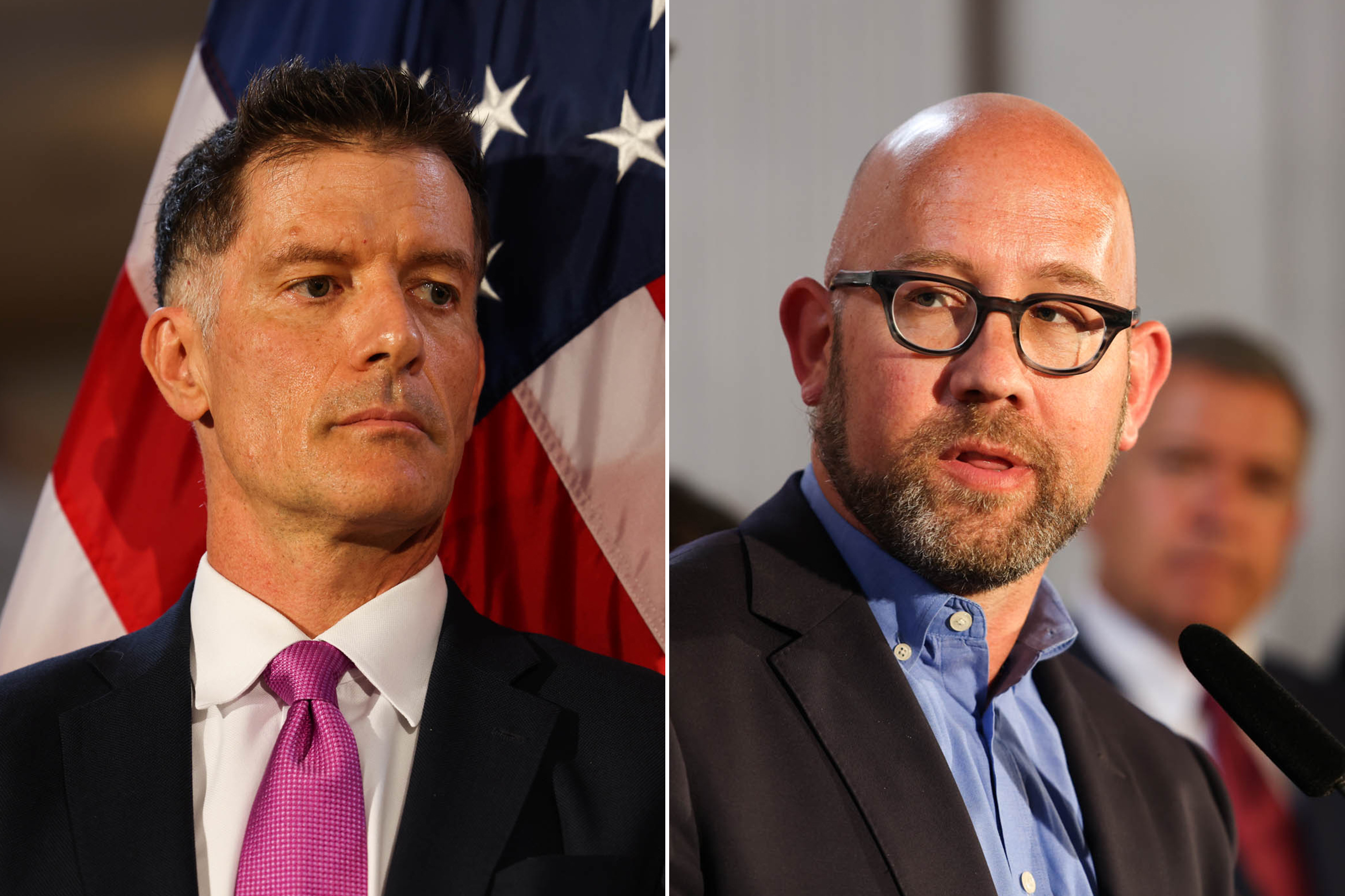

Supervisor Rafael Mandelman is calling for a hearing on Tuesday to ask the Department of Public Health to own up to its inability to provide sufficient drug addiction treatment.

The hearing will focus on the annual treatment on demand report, last released in January 2022, which is intended to measure gaps in the city’s substance abuse treatment network. But Mandelman said that the report doesn’t adequately capture the demand for treatment because it surveys people who are already enrolled in rehab, leaving policymakers in the dark when attempting to allocate resources for the uninitiated.

“The tendency in every bureaucracy is to put on as happy a face as you can and insist that you have things under control,” Mandelman said. “It gets better with daylight, when these things don’t just go into a drawer and we actually have a hearing and talk about them.”

Mandelman said he hopes that the hearing will lead the Department of Public Health (DPH) to provide a more detailed analysis on what is needed to reach the city’s treatment on demand goal, which was introduced by the Board of Supervisors in 1995 and further cemented by voters in 2008.

Despite this longstanding policy goal, the city appears to be falling well short of making treatment of demand a reality amid a soaring rate of fatal overdoses.

Of 11,570 people diagnosed with substance abuse disorders in 2020, less than half received treatment for their addiction, according to the report. A city dashboard displays 49 available substance use treatment beds at the time of publication.

The most recent treatment on demand report describes an average 1.1 day wait time to enter substance abuse treatment for people exiting a withdrawal management facility, a hospital or jail. And people not exiting those institutions wait an average five to seven days for treatment, according to the report.

“There are people who will not wait five to seven days,” Mandelman said. “Are we gathering information about the people who don’t even make it into the system?”

The number of people entering drug treatment in San Francisco has decreased alongside rising overdoses, according to a seperate city dashboard. The Department of Public Health said in a statement that it attributes this decline to the pandemic, as well as nationally changing admission standards and new programs that altered how individuals accessing programs were counted.

Mandelman said that DPH has been hesitant to report facts that would reflect poorly on their department and that this creates problems for policymakers who need to quantify the crisis in order to properly allocate resources.

Workers at the city’s methadone clinics told The Standard in July that they are often forced to turn patients away due to a lack of staffing. DPH disputed those reports, issuing a statement that said, “our contracted methadone providers report no delays in initiation of care.”

Marlene Martin, founder of Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital’s Addiction Care Team, said that the most difficult part of connecting people to substance use treatment is navigating an intricate web of paperwork and “authorizations.”

Martin said that language barriers and complicated psychiatric diagnoses can result in a patient waiting weeks before entering treatment, sometimes having their referrals expire before they’re authorized for treatment. Others may enter right away.

“Not everyone needs residential treatment, but when people do want it and that’s an option, navigating that system can be tough,” Martin said.

The city spent $71 million on services for substance abuse in 2021, but a persistent shortage of health workers has stymied some of those programs. The problem is widespread: The U.S. is about 1.9 million behavioral health workers short of addressing its drug addiction crisis, according to a survey by the federal Substance Abuse and National Mental Health Services Administration.

“Treatment on demand, in and of itself, would not solve the city’s open air drug scene but I think it’s pretty important to the package of things that could solve it,” Mandelman said.