Gov. Gavin Newsom announced an ambitious new plan Thursday to get people off the streets if they are suffering from mental health and substance abuse issues. The CARE Court, whose title includes an acronym for Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment, would require counties to provide comprehensive treatment to these populations and hold individuals accountable for completing their treatment.

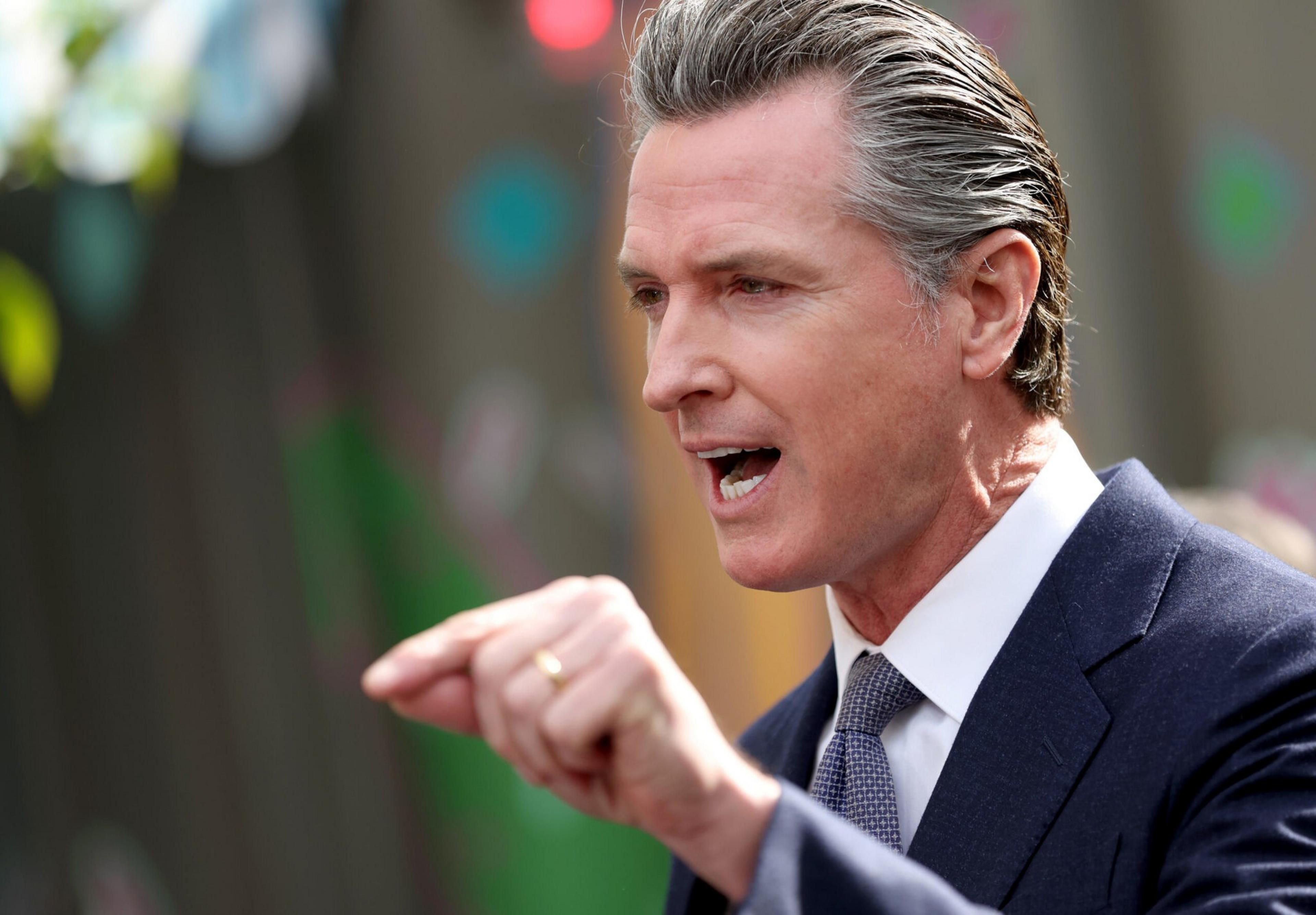

The governor announced details (opens in new tab) of the plan in a press conference at a mental health facility in San Jose that included a number of big city mayors across the state and Dr. Mark Ghaly, the state’s top health official.

“There’s no compassion stepping over people in the streets and sidewalks, there’s no compassion reading about someone losing their life (opens in new tab) under (Highway) 280 in an encampment,” Newsom said. “We can hold hands, have a candlelight vigil and talk about the way the world should be, or we can take some damn responsibility to implement those ideals.”

So how does it work?

Essentially, the CARE Court program would create an alternative system within the civil courts to help residents dealing with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, as well as those struggling with substance abuse—basically, anyone who lacks the ability to make medical decisions for themselves. Superior Court judges in each county would then be able to connect individuals with a personalized court-ordered care plan, as well as a court-appointed peer supporter to help the person abide by the plan.

Will this lead to people being taken into custody off of the street?

Individuals would be brought to the CARE Court system via a number of paths. They can be referred by a clinician, put into the system when their involuntary psychiatric hold ends or be diverted into the program from criminal prosecution. Family members, first responders and community-led health care teams can also help refer individuals into the program. The person would have a public defender to represent them in the CARE Court system and ensure their civil liberties.

How long will someone be in the system?

The plans could last as long as 24 months and can include a number of treatment options, including short-term stabilization medications, recovery support and connections to social services like housing with wraparound services. These services would be provided via an outpatient model centered in the communities where the individuals live.

Is this just another name for conservatorship?

Not according to the state officials who are calling it a “new tool” to address homelessness and mental health issues. If an individual fails to complete their court-ordered plan, they can then be referred to a conservatorship or back into the criminal court system. Officials say this abides by current law, which holds conservatorship as an option of last resort when no suitable alternatives can be found.

Where will the program apply?

Each of California’s 58 counties would be required to participate in the CARE Court program. If local officials fail to roll out the program, their county may be subject to sanctions and—in extreme cases—a state agent may be appointed to ensure compliance.

Why is this happening now?

Newsom, the former mayor of San Francisco, pointed to his hometown’s crises around homelessness and mental health, and how the state overall has reached a breaking point. He added that California’s current laws governing mental health issues are outdated and the state often uses conservatorship or incarceration as a primary option to deal with the issue, as opposed to a more compassionate approach based on treatment. CARE Court would be part of Newsom’s larger strategy against homelessness, which includes investing $14 billion toward 55,000 new housing units and treatment beds. “We need to treat brain health early before we punish it later,” Newsom said.

What comes next?

Currently, the CARE Court program is just a policy framework and it needs approval from California lawmakers to move forward. Newsom’s administration is weighing whether to try to pass it through the budget process or through a separate piece of legislation. The governor said he hopes to get it passed by the end of the year.