Outfitted with 20 beds as well as showers and bathrooms, a new sobering center will open its doors in SoMa on Monday to people who are coming down from the effects of drugs such as methamphetamine and fentanyl.

But SoMa Rise is opening in the heart of one of the city’s most notorious open-air drug markets, prompting concerns from neighbors who allege that the site will attract more drug dealers to the area and worry that the city will not provide adequate resources to address other related issues likely to pop up.

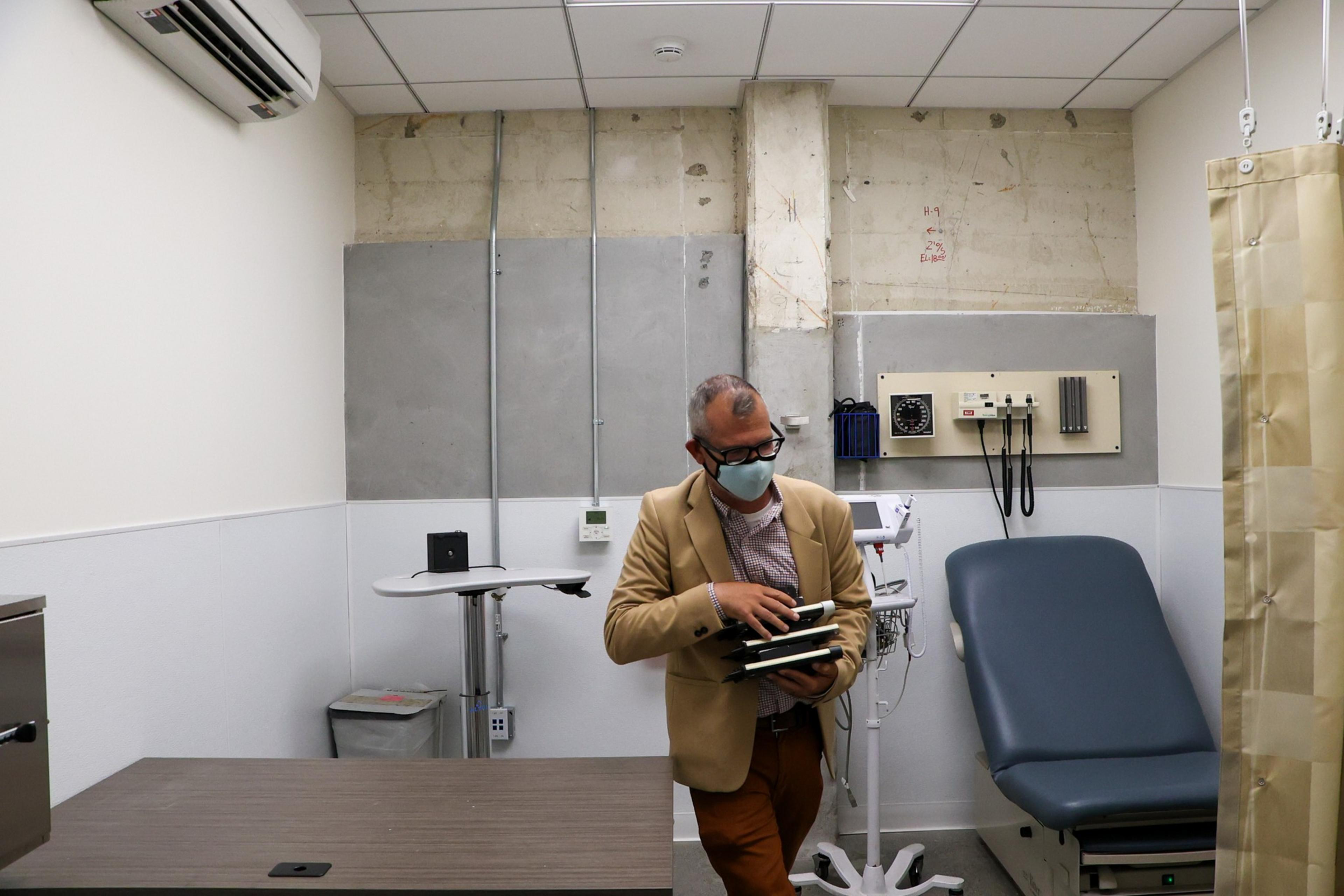

The city is tapping the drug health nonprofit HealthRight 360 to run the center at 1076 Howard St., which has been in the works since 2019 and has a first-year operating budget of $3.5 million, according to the Department of Public Health. The idea for SoMa Rise originated as a recommendation from the city’s Methamphetamine Task Force as a place for people suffering from drug related crises to access services and find treatment options.

SoMa Rise may help alleviate a void left by the Tenderloin Center, a facility that has offered hygiene, medications to reverse drug overdoses and housing support services to thousands of people since January. The Tenderloin Center is set to shutter by the end of the year amid criticism that it failed to link drug users to treatment services.

Like the Tenderloin facility, SoMa Rise is struggling to win the support of the neighborhood as some residents voice concerns about where program clients will go when their anticipated four- to 12-hour stay at the center is over.

“It’s one of those things that nobody wants in their backyard,” said Christian Martin, the executive director of the SoMa West Community Benefit District. “If you’re going to put it in this neighborhood, at least give us more resources to deal with the inevitable blight that comes with it.”

The facility will not allow people to use drugs on the site and HealthRight 360 is employing peer ambassadors who will roam the surrounding area and gently guide people into the center.

This is unlike the controversial model employed at the Tenderloin Center, which has a designated area enclosed by fences in front of the building for supervised drug use. That facility is also run in part by HealthRight 360 and located just two blocks away from the SoMa Rise building.

SoMa residents have decried the neighborhood’s deteriorating conditions following Mayor London Breed’s December state of emergency declaration, which allocated additional police and ambassador personnel into the Tenderloin neighborhood, pushing drug-associated crimes into neighboring districts.

Chief of Police Bill Scott said at a Police Commission meeting earlier this month that the San Francisco Police Department is upping narcotics enforcement in the SoMa area to respond to an increase of drug dealers and violent crimes connected to the Tenderloin.

And in May, Breed appointed former SFPD spokesperson Matt Dorsey as the interim District 6 supervisor, which oversees SoMa, pointing to his personal experience and his stated focus on dealing with the neighborhood’s drug crisis.

Having recovered from drug addiction himself, Dorsey has said he intends to address open-air drug use and dealing by striking a balance between enforcement and treatment.

Dorsey told The Standard that he sees the SoMa Rise Center fitting into his newly proposed “Right to Recovery” legislation, which would ramp up law enforcement of narcotic related crimes on blocks that have drug treatment and drug-health facilities.

“We have to make a commitment to the neighborhood and to community leaders that these kinds of facilities, which we need more of, are not going to become a magnet for public nuisances,” Dorsey said. “We need a policy that is going to both protect the people who are seeking services and assure the neighbors that it’s not going to be a problem.”