One day this spring, I left my house in the Mission District at 5:20 a.m. and biked 140 miles to Sacramento. It took nearly 15 hours, though I didn’t spend all that time in the saddle.

About halfway to the state capital, in the heart of the Sacramento River Delta—a 1,000-square-mile region that’s been made and remade to balance agriculture against flood control, I came across the town of Locke, which may well be the only extant rural Chinatown in America.

Founded as “Lockeport” in 1915, it’s 75 miles northeast of San Francisco, 30 miles south of Sacramento and not far from a drawbridge that recently got stuck in the open position (opens in new tab) overnight. It abuts the Sacramento River at the junction of two since-disappeared railroad lines, which once shipped crops like asparagus to the burgeoning cities of San Francisco and Stockton.

Over a century since its founding Locke’s utility as a river-and-rail distribution hub has dwindled almost to nothing, even as the Central Valley’s importance for feeding America has ballooned. Its several dozen residences sit on thoroughfares that are often streets in name only, non-navigable to cars (and hazardous to road bikes). Main Street’s pavement is in lawsuit-baiting disrepair, its structures in various states of photogenic collapse. The town appears destined to die spectacularly in one of three ways: flood, fire or Disney-fication.

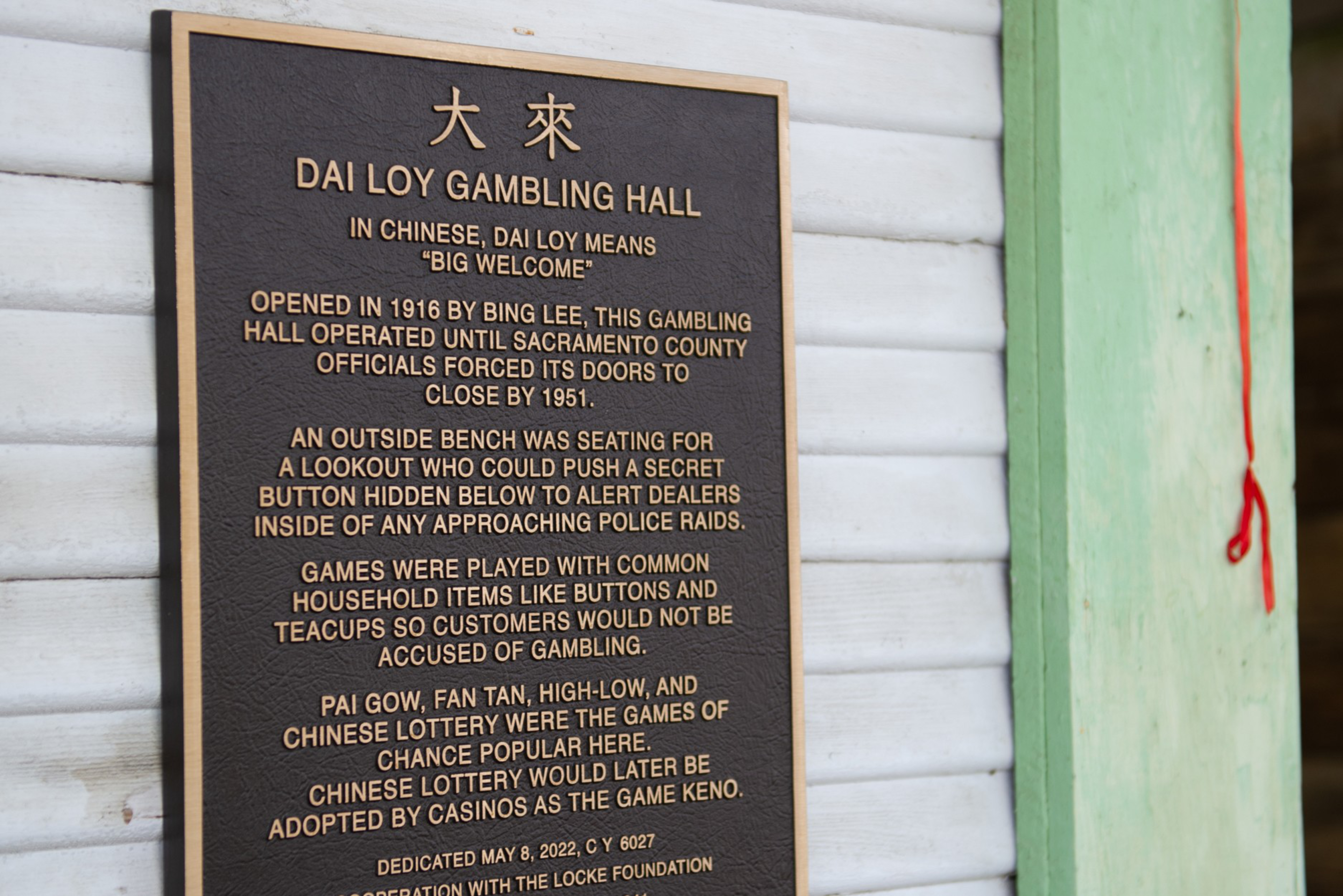

It may be hot, marshy and gradually ceasing to be a place. But Locke is also a rarity: a living monument to Chinese American culture in turn-of-the-last-century California. Unlike ephemeral boomtowns populated by Chinese laborers, or the Chinatown in nearby Walnut Grove—lost to fire in the 1930s—Locke is still here, with the musty Dai Loy (opens in new tab) and Chinese School Museums and a number of plaques preserving its heritage. Today, though, there are more Latinos than Asian Americans, and the liveliest business is a hundred-year-old bar with hundreds of dollar bills tacked to the ceiling and the impossibly un-PC name “Al the Wop’s (opens in new tab).” (Google Maps tactfully lists it as “Al’s Place.”)

As with the larger Isleton, another Delta town whose Chinese architecture remains well-preserved, you enter Locke by descending from River Road, which sits atop the berm that keeps the waters of the Sacramento out. That’s what I did—on a whim, knowing nothing about it, approximately 115 miles into what would be my all-time longest ride.

“Free water for cyclists!” a voice called out from inside Lockeport Grill & Fountain (opens in new tab), one of only a handful of businesses in town. That was how I came to meet the headstrong proprietor, the visual artist and self-proclaimed “Air Adventurer” Martha Esch, a force of nature who was going to make me a grilled cheese whether I wanted one or not.

A Walnut Grove resident, Esch runs the delightfully kitschy soda fountain as well as the six-room bed-and-breakfast above it. She docks a boat that sleeps 12 in a covered marina on the Delta community Bethel Island, not far from a raucous maritime dive called the Rusty Porthole, and with easy access to Ephemerisle (opens in new tab), the annual summertime gathering that’s been called Burning Man on boats.

A quiet historical district like Locke would seem to be an improbable landing place for such a daredevil, one who “air-hitchhiked” across the Lower 48 in 1988—almost like banishment to a penal asteroid. But from her base of operations, the Ohio native’s passion for researching Locke’s history has made her a cultural asset in her own right.

Esch has compiled records from numerous now-defunct print publications, piecing together some of the history of the building and of the town itself—which seem to go back a bit further than the 1915 founding date suggests. She believes her building dates to the 1800s, and claims to have found an 1893 deed at the Recorder’s office that mentions “Lockeport, California,” which was shortened to Locke around 1920. Town namesake George W. Locke was a businessman and land owner whose generation subdued the sprawling Delta with an enormous public-works project of berms and levees.

This seems to contradict the museums’ accounts of the town’s history, which seem to downplay George W. Locke in favor of the resilience of the early-20th-century Chinese Americans who constructed the levees (opens in new tab). Esch’s proof can be found on the restaurant’s walls, along with a clipping from the now-shuttered River News Herald that might be charming if not for the stakes involved (“Barking Dog Helps Save Locke from Fire”). Elsewhere, I found apothecary jars filled with candy and a player piano reserved for the house poltergeist, Ghosty. To one side is a cramped psychic’s room partitioned off with a beaded curtain. To another, a little gambling parlor where Esch lost a dollar to me in roulette.

As a kind of opium den crossed with Tombstone, Arizona, Locke’s vibe has proven itself irresistible to film crews, from Clint Eastwood’s 1988 Bird to 2020’s pulp-horror Psycho Pomp. In July, a production company shot a teaser for a project (opens in new tab) based on Ruth Galm’s novel Into the Valley, about a young woman in 1960s San Francisco who falls in with the wrong guy. Esch let the team dress her soda fountain as an Old West-style bar for free for two days—as long as they rented out the entire B&B both nights.

Apart from the classic rock blaring from Al’s and the curious onlookers struggling to photograph Main Street’s sagging buildings from the right angle, that’s about as much action as Locke sees. Plans to redevelop the town have consistently come to naught, with the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors nixing a fanciful 1990s-era plan to buy most residents out and maintain it as a historical park. It seems to exist in a kind of uncomfortable stasis, and it feels bizarre that within two hours I’ll be riding through Downtown Sacramento, on the other end of the Delta and famished again.

So why stay in a place that Esch winkingly dismisses as “deadsville”? Well, she owns her building outright, and the bizarre, compact streetscape offers constant opportunities to paint.

“You can’t make them all the same,” she says, referring to the town’s buildings as well as her depictions of them. “Each porch is a little bit higher or lower than the next one, and it sways this way or leans down, and they’re all crooked.”

If you go…

To visit the Sacramento Delta from San Francisco, take the Bay Bridge to Interstate 80 north and then onto California State Highway 4. In Antioch, turn onto Highway 160, which carries you over the Antioch Bridge and into the Delta. (The writer does not recommend biking the full 100-plus miles.) The riverside communities of Walnut Grove and Isleton have accommodations (opens in new tab), restaurants (opens in new tab) and bars—the beer selection at Isleton’s Mei War Beer Room (opens in new tab) is thoroughly excellent—while the enclosed Delta Farmers Market at the crossroads of Highway 160 and Highway 12 is a veritable agricultural complex, complete with restrooms. In Locke, the Lockeport Grill & Fountain may keep irregular hours, while Al’s Place remains open later into the evening. Allow at least two hours each way, more if you are seduced by the Delta’s magic.