Two-and-a-half years after the start of the Covid pandemic, San Francisco’s downtown is still a shell of what it once was, and the economic outlook, for the short term at least, is ominous.

But just a few miles south, business is back. In South San Francisco, a self-styled “industrial city” that shares little of the glamor of its northern neighbor, restaurants and coffee shops along main thoroughfare Grand Avenue are abuzz with customers. Construction cranes dot the landscape, and east of Highway 101, the city’s corporate campuses and industrial hubs hum with activity. A few storefronts downtown are shuttered, and small business owners say they’ve been through the wringer, but the city’s economy has proven far more resilient than that of SF.

A big part of the secret sauce for South City is its standing as the “birthplace of biotech.” Unlike the software business, which today accounts for about 30% of San Francisco’s office market, biotech relies heavily on in-person work, making it a far more durable local industry in the Covid era. Genentech, South City’s largest employer by far, was considered an “essential business” with 3,000 to 4,000 people still in-office during the pandemic, and today it averages around 9,000 people on-site each week.

But there are other factors, too. Companies cite the relative ease of navigating the city’s bureaucracy and a welcoming approach to new development which, together with assets like proximity to major transit hubs, has helped the city build on its strength as a center for biotech and manufacturing. Tech firms such as payment leader Stripe, which decamped from San Francisco in 2019, now also find it a welcoming home.

At a ribbon-cutting ceremony last week celebrating a new lab built by Amgen, the global pharma giant, South San Francisco Mayor Mark Nagales touted some 9 million square feet of new research and development space that’s in the pipeline. South San Francisco has issued over 2,000 commercial building permits and around 3,000 residential permits since the start of 2019, totaling $3 billion worth of construction, according to the city.

“You are right where you belong,” Nagales told a boisterous crowd of Amgen employees on Thursday, including CEO Bob Bradway, who flew in for the event from Switzerland.

Comparing San Francisco and its southern neighbor is not entirely fair: With a budget of just $122 million, it’s a veritable small town next to San Francisco, whose annual spending nears $14 billion. Even compared with other cities on the Peninsula, its downtown is quaint, with a historic City Hall and library and ample dining but only a modest retail scene.

Still, its pandemic-era resilience and can-do approach may hold some lessons for its bigger and more famous neighbors.

“South San Francisco—they didn’t close their doors,” said Rosanne Foust, president and CEO of the San Mateo County Economic Development Association. “They stepped up.”

Leave it to Biotech

South San Francisco, like many other cities on the Peninsula, got its modern start as a transportation and manufacturing hub. The industrial parks on the eastern side of the city were occupied first by meat-packing and steel companies in the 1920s, followed by shipbuilding in the ’30s. In the 1950s, freight and distribution of various types began to thrive as its marshlands were converted into even more industrial land to support the San Francisco International Airport.

The game-changer came in 1976 when Genentech chose South City as its home because of its proximity to both SF’s industry and the Peninsula’s academia. The company proved to be a seminal force in the creation of the biotechnology industry, pioneering both scientific and business advancements in the field, and it stuck to its original home even after being acquired by Swiss pharma giant Roche in 2009.

Today, there are more than 200 biotech companies located in South San Francisco, accounting for about 30% of the city’s jobs, according to data from the city’s general plan. Genentech (opens in new tab) and fellow biotech giants Abbvie (opens in new tab) and InterVenn Biosciences (opens in new tab) have all expanded in South City or renewed their leases recently. Earlier this year, 23andMe (opens in new tab) and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (opens in new tab) both announced plans to move their headquarters to South SF from Sunnyvale and Oakland, respectively. The latest rumor (opens in new tab) is that Eli Lilly and Co. is hunting for 300,000 square feet of additional space in the city.

South San Francisco had the “strongest submarket” among Peninsula cities for research and development space in the most recent quarter, according to data from real estate broker CBRE (opens in new tab).

And it’s not just biotech. True to its famous hillside signage, “The Industrial City” has around 28% of its jobs in production, distribution and repair. Despite regional stagnation, South City’s industrial market logged four of the top five notable sales and leases in the area for the most recent quarter.

One major new development on the horizon is Southline (opens in new tab), a 28.5-acre campus whose plans were unanimously approved by the South San Francisco City Council earlier this year. Marcus Gilmour, principal at Lane Partners, the developer on the project, said demolition and site work began this year and the group is in the process of getting foundation permits for the 2.8 million square feet of planned office and research and development space.

Gilmour said the process to get Southline through the city’s pipeline was “robust” but efficient.

“One of the things that stood out to me […] was their team was very responsive,” Gilmour said. “The priority is protecting the city and understanding the impact but also wanting to see the project go forward if it was really the right fit, so it was really more of a partnership than what I’ve typically seen in the Bay Area.”

For the most part, South San Francisco has been accelerating its housing building on par with the rest of San Mateo County, especially for higher-density development, according to data (opens in new tab) from Jon Haveman, principal at Marin Economic Consulting.

Nell Selander, director of South San Francisco’s Economic and Community Development Department, said the city’s development pipeline didn’t slow down as much as other places during the pandemic because the city made a concerted effort to keep its planning and building offices up and running.

South San Francisco’s average of 342 days (opens in new tab) from submitting plans to getting the key approval known as entitlement is well below the 450 days it takes San Francisco, according to data from the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development.

“If you need or want to expand in South San Francisco, you’re going to get a pretty clear and straightforward process,” Selander said.

Like many other cities, South San Francisco does charge a number of impact fees for new development, totaling $134 million since the start of 2019. During the 2020-21 fiscal year alone, the city collected $21.5 million in impact fees across eight programs for things like childcare, arts, parks and libraries.

Included in that is a fee requiring commercial developers of office, research, development and medical space to pay $15 per square foot toward an affordable housing fund. The city expects to collect $85 million over the next four to five years just for housing in South City, according to reporting from The San Francisco Business Times (opens in new tab), which includes $30 million over the next 15 years from Genentech as the company updates its campus.

While those same impact fees often scare away developers in San Francisco’s costly building market, Foust said they haven’t had the same effect in South City. While San Francisco does not charge an affordable housing fee for commercial development, it does have many other types of impact fees. SF’s affordability requirements for housing developments are modestly more stringent than in South City.

Saptarsi Haldar, Amgen’s vice president of cardiometabolic research and the site head for the new South City location, said Amgen and other biotech companies continue to choose South San Francisco for a few reasons: It’s already a hub full of talent with world-class education institutions nearby; it’s surrounded by freeways, transit stops and an international airport; and unlike traditional tech, biotech and life sciences doesn’t up and leave so easily because of the complex and long-range nature of the work.

The global biopharmaceutical company has been in South San Francisco since 2004 and signed a lease for a new facility in Oyster Point in 2019.

“Because companies have invested so heavily in the city, it makes sense for them to double down rather than to start over somewhere else,” said Jeff Bellisario, executive director of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

Help From Above

The relative stability of the big biotech companies doesn’t mean the pandemic was easy for small businesses in South City.

Montserrat Mata, who co-owns Antigua Coffee Shop with her husband, said the downtown really only started coming back to life a couple of months ago. That coincided with companies like Genentech starting to bring back nonessential workers for more regular in-office work and the revival of its “Genentech Goes to Town” program, which gives every employee $25 to spend at local shops.

Like many other owners, Mata had to transform her business overnight, pivoting to delivery and outdoor dining as demand plummeted. Mata says her coffee’s reputation among locals is what kept Antigua alive, alongside relief funding and money for outdoor seating, like a grant from the city’s Chamber of Commerce that was funded by Genentech.

“We were struggling a lot,” Mata said.

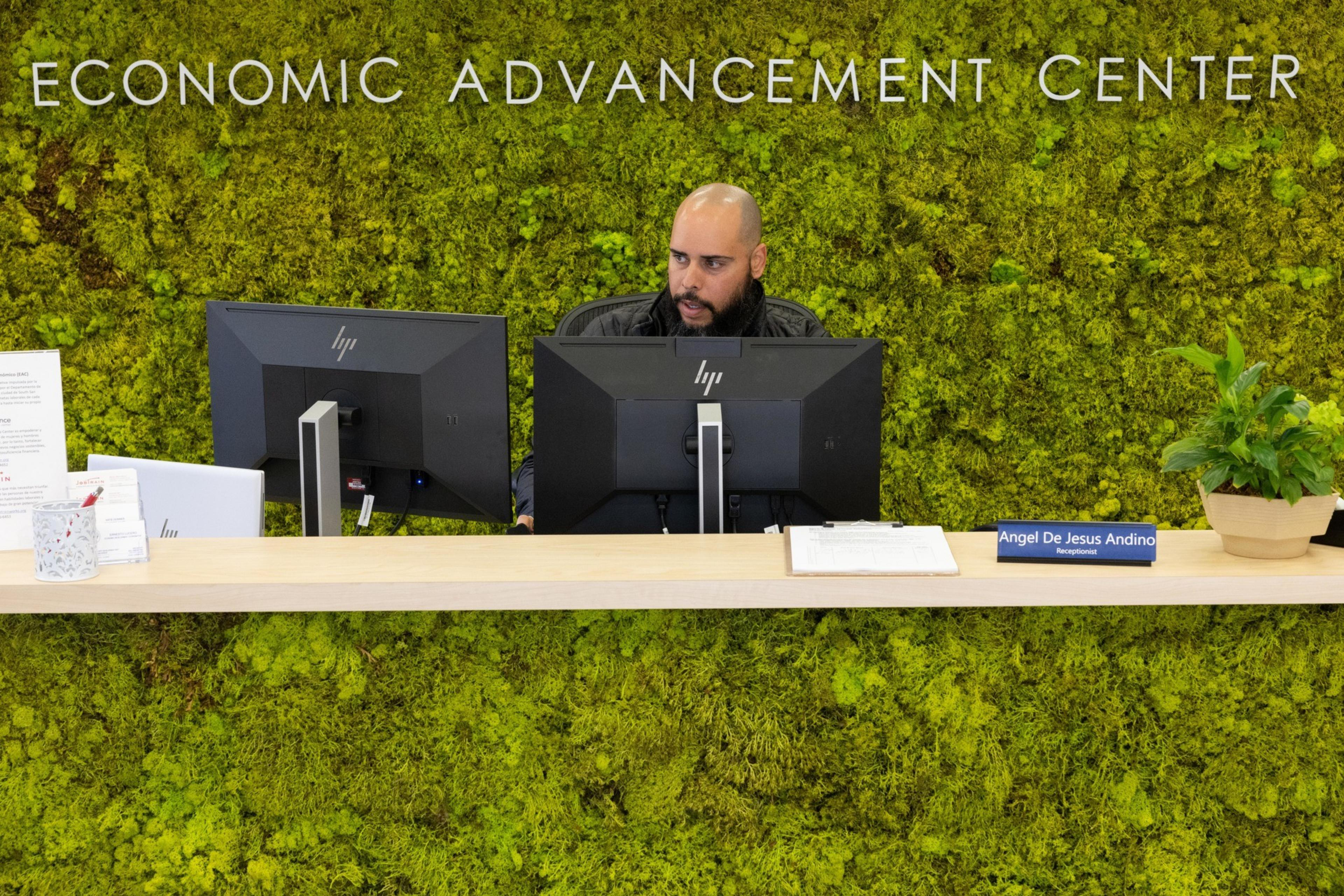

Alongside the chamber, nonprofit Renaissance Entrepreneurship Center stepped out of its normal role helping to launch small businesses and got to work on relief, said Amanda Anthony, program manager for its north San Mateo County branch. And in 2021, the City Council dedicated $2 million of its federal relief funding to open an Economic Advancement Center (opens in new tab), a physical space downtown for small business services and job training. The center also got support from the county, the San Mateo County Economic Development Association and money from Genentech and Lane Partners (opens in new tab) with programs run by Renaissance, the local YMCA and the nonprofit JobTrain.

One county program in particular, Great Plates Delivered, connected struggling restaurants with homebound seniors who needed fresh food delivered. Participation in that program allowed food truck owner Feda Oweis, who often catered to biotech offices and events, to stay afloat during the early days of Covid.

Now, Oweis has moved his truck, called Beyond the Border, into a storefront on South Linden Avenue and is looking to buy a second truck to keep up with demand. As office work returned, so did his catering business.

Oweis crafted his menu at the new location to fit the customer base, offering quick lunch bites for workers in the surrounding factories and warehouses. He’s looking forward to when Southline, which is just down the road, gets built. He’s even partnering with the city to pass out fliers and appetizers to customers next week, saying, “It’s always busy year-round.”

As for the city’s culture, Mata said it might take a bit more time and effort to really bring back the feeling of the pre-pandemic days when Grand Avenue stayed open and bustling well into the night. But if it’s up to her, it won’t be long.

“We have a lot of plans,” Mata said. “In the end, this is a place open for the community.”