Back in 2019, San Francisco established an office to regulate “emerging technology.” But that office, fashioned at the height of the city’s tech boom and located in close proximity to the industry’s epicenter, never quite emerged.

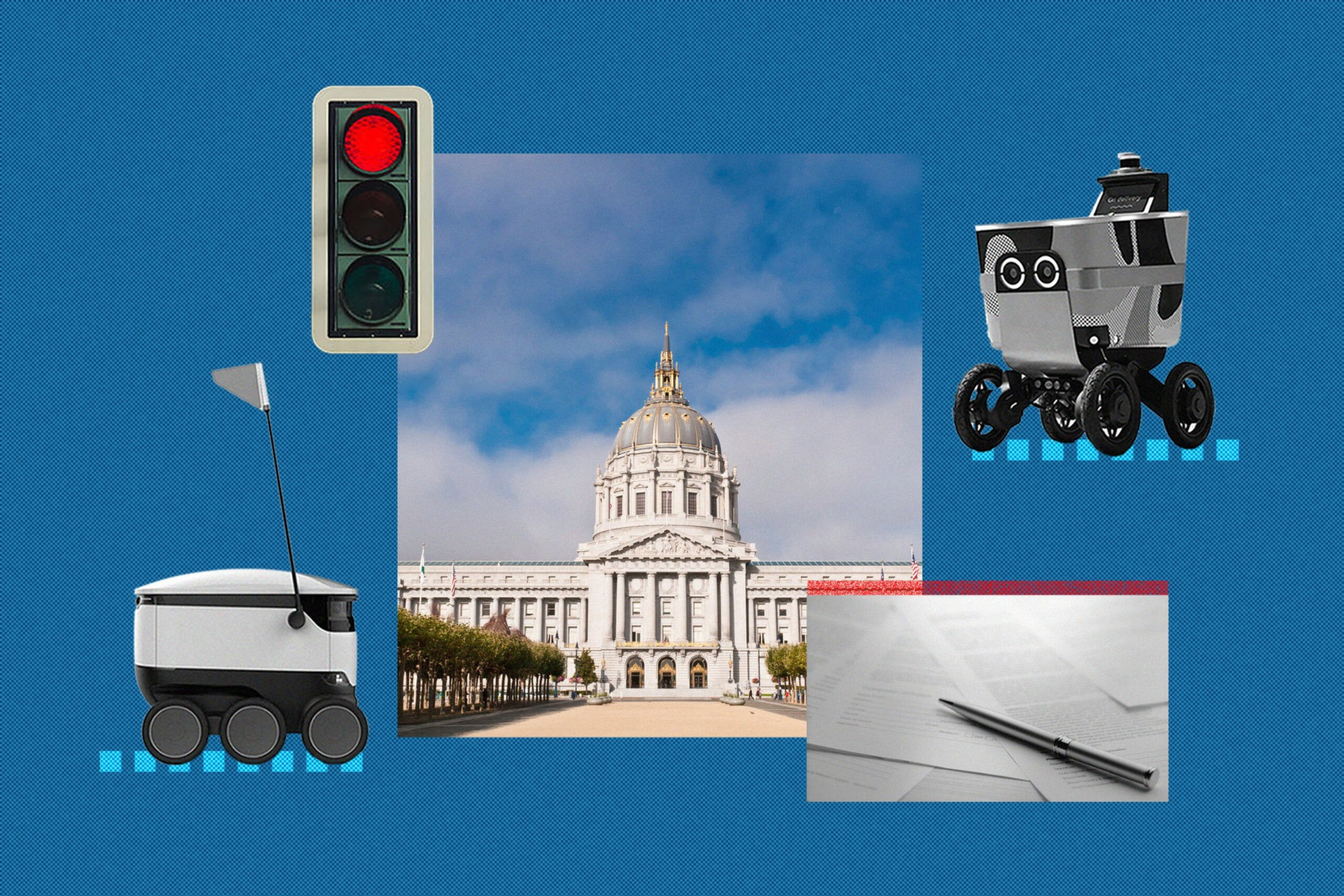

Conceived by lawmakers at a time when sidewalk robots, powered scooters and dockless bike shares were increasingly roaming the streets unsupervised, the years-in-the-making Office of Emerging Technology was meant to make it easier for companies to get permission to pilot cutting-edge products in the city while also serving as a bridge to the tech industry and its regulators.

But nearly three years later, the office hasn’t issued a single permit—there have been zero completed applications. It has never filed an annual report or followed up on requirements to convene stakeholders, forecast trends and collaborate with industry groups. Despite being well-funded, it never even hired a full-time director, The Standard found through interviews and public records.

The office fell victim to rampant dysfunction within the Department of Public Works resulting from the indictment of its longtime head Mohammed Nuru on corruption charges, as well as the chaos caused by the pandemic.

And while the Office of Emerging Technology languished, many of the tech companies that office was supposed to attract simply moved on: Robotics companies are testing and operating devices in other cities across the country, but none are piloting their services on San Francisco’s sidewalks.

“It would be helpful to have greater clarity for what boxes need to be checked to become operational, consistency in terms of who receives permits and who does not,” said Vignesh Ganapathy, who served on a city emerging technology working group while working at Postmates.

The city said it plans to “reset” the office after The Standard’s inquiry.

Whack-a-Mole

In February 2017, Dispatch, a South San Francisco-based tech firm, began testing (opens in new tab) its delivery robot in the Mission District. Other companies followed, plunking down prototypes on city streets in the hopes of launching in the heart of the tech economy.

A backlash soon followed: Critics decried the delivery robots and their ilk as sidewalk-clogging, job-killing menaces that ought to be eliminated or subject to tight controls. City lawmakers, led by then-Supervisor Norman Yee, passed heavy restrictions (opens in new tab) on robotics companies by year’s end.

As March 2018 rolled around, more tech-fueled devices were entering the fray. A gaggle of powered scooter and dockless bike network companies deployed their products (opens in new tab) across San Francisco. The city impounded dozens of them for blocking sidewalks and went to the drawing board again to write new regulations.

But this time, the Board of Supervisors also directed the City Administrator’s Office to convene a committee composed of representatives from tech companies, labor groups, nonprofit organizations and city staff to find a long-term solution.

In a report (opens in new tab) a few months later, the Emerging Technology Working Group issued a set of recommendations, chief among them was to create an office for emerging technology.

Yee introduced legislation to create the office, amending city codes to place it inside the Department of Public Works with an annual budget of $250,000 and the power to issue permits and level administrative, civil and criminal penalties against scofflaws.

“It’s not just about regulation; it’s about safety, it’s about access, it’s about developing a system that works,” Breed said at a press conference heralding the new office.

Yee said the office would handle hoverboards, delivery drones, data-gathering devices on public spaces—possibly even a pogo stick network (opens in new tab).

The idea received broad support from Breed, the Board of Supervisors, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce and a cavalcade of other organizations.

But it also drew scorn from some prominent tech leaders who rolled their eyes at the idea of city regulation of innovative new products.

“Why would you found a new tech company in San Francisco?” tweeted Balaji Srinivasan, a prominent investor and tech founder, in response (opens in new tab). The Silicon Valley Leadership Group, founded by David Packard of Hewlett-Packard, decried the new permit system (opens in new tab), saying it would stifle innovation and burden businesses.

Failure To Launch

The Office of Emerging Technology has never received a permit application and only a handful of inquiries have come in over the years, Rachel Gordon, the director of policy and communication for Public Works, said.

The office and the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency coordinated on inquiries from networked storage provider Coffr, car membership company Upshift and robotics company Orca Mobility, according to the departments. But none resulted in a permit application.

Upshift’s Ezra Goldman said the office told him that his company’s service was not under their purview.

When Gap, the city’s homegrown conglomerate clothing retailer, consulted the office for permission to operate a robot security guard at its headquarters on the Embarcadero last year, the office directed the company to file a permit, records show. Other officials in Public Works then denied the permit for being improper.

As it stands today, the office is a far cry from the vision laid out in 2019.

The legislation creating the office calls for staff who are “qualified technology professionals” or possess knowledge of the city’s community values and regulations. Instead of hiring for the roles, Public Works added the office’s responsibilities to a bureau manager’s workload.

Detailed questions about the office’s compliance with the legislation were not answered by Public Works. Aside from regulation, the office is supposed to monitor emerging technologies; host events with the tech sector; research the effects of emerging technologies use on city residents and resources; and assist lawmakers in policy development, among other services

In a statement, Gordon of Public Works blamed staffing constraints and competing demands during the pandemic for the office’s failure to launch. The office “has not taken proactive steps related to the recruitment of a permanent director, hosting forums and the like,” she said.

Gordon added that now is an opportune time to “hit reset and see what steps are needed to move the legislated initiative forward.”

Ganapathy, who now works in public policy at Serve Robotics, said that the office was an idea, but that the city should collaborate more closely with the private sector to ensure such initiatives succeed. Today, Serve operates delivery robots in several jurisdictions—but not in San Francisco.