The head of the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park sent a letter in September that “cordially invited” parks chief Phil Ginsburg to a meeting relating to the museum’s new mission to “regenerate the natural world” in San Francisco.

The invitation got a less-than-cordial response. Ginsburg sent a Sept. 16 email that all but called the museum’s director, Scott Sampson, a hypocrite for promoting Cal Academy as an environmentalist institution while simultaneously failing to support the city’s efforts to remove cars from John F. Kennedy Drive.

“Given the Academy’s continued and regrettable lack of leadership on protecting the City’s climate adaptation efforts,” Ginsburg wrote in response to the invitation, “I am having a hard time assessing the substance of this new initiative and what a collaboration might yield.”

Tuesday’s ballot has three measures intended to finally resolve a half-century old fight over a mile-and-a-half stretch of asphalt that the park’s museums would like to remain a parking lot and vehicle thoroughfare, while those advocating to keep a “JFK Promenade” wish to see it reserved for recreational activities such as strolling, bike riding and playing.

This struggle—over whether people should be able to drive to and park at popular city attractions, or whether car access should be limited to enhance those attractions’ recreational value—has gone on at JFK Drive back to the 1970s. And Cal Academy, which showcases environmentalism-themed learning, has, from the beginning, been an annoyance to those who want to clear cars from that stretch of road.

In 1973 prominent columnist Herb Caen weighed in on a then-new move to keep cars off John F. Kennedy Drive on Sundays: “The rarest treasure, Golden Gate Park on a car-free Sunday morning,” he wrote, “the air wet and clean, the meadows green with the promise of spring. Not a single automobile: The silence is deafening, you can actually hear the branches dripping moisture.”

Four years later, Cal Academy director George Lindsay fired off an impassioned letter (opens in new tab)asking the Recreation and Parks Commission to reject a proposal to extend the policy to holidays. “Any action on such a proposal should be deferred until full consideration of all the problems and hardships caused by the park closing can be presented,” he wrote.

In response to a request for an interview on the matter, a spokesperson for Ginsburg said he preferred to let the letter speak for itself. A spokesperson for Sampson said a Cal Academy official could only speak to The Standard several days after deadline.

Today, Cal Academy has not taken an overt position opposing a car-free JFK Drive. During earlier such battles, Cal Academy joined in the chorus of voices protesting that reduced street parking near the museum would reduce admissions revenue. And indeed, it experienced an admissions revenue drop from from 2020 to 2021 of approximately $8 million, according to financial statements that list its assets at $832 million. Even the revenue loss due to Covid closures was dwarfed by Cal Academy’s net investment revenue during that period of $57 million, suggesting admission fees represent a small portion of the museum’s budget.

Notwithstanding, there is evidence pointing to the possible origins of Ginsburg’s ire.

The city is spending a combined $200,000 on changes to the road to encourage a future that would be car-free.

Last year, Sampson tweeted that “the Academy is not against #carfreeJFK. We simply seek an open and transparent process that includes a traffic study, community engagement, & an opportunity to discuss alternatives.”

Sonja Trauss, director of YIMBY Law, an advocacy group that injects itself into land-use disputes, has become expert in interpreting the language used in such controversies.

“This is coded language. This is the way that San Franciscans politely say, ‘I hate your idea, and I don’t want to do it,’” she said when asked about Sampson’s tweet. “If you don’t agree with what’s being done, you find a way to put off the next step, and that’s what they’re doing.”

Cal Academy has meanwhile been marketing its new focus on biodiversity in San Francisco and across California. In January as the JFK Drive controversy heated up, Cal Academy also proposed to the parks department replacing some statues in Golden Gate Park with giant copper-colored depictions of insects (opens in new tab), which turned out to be a nonstarter.

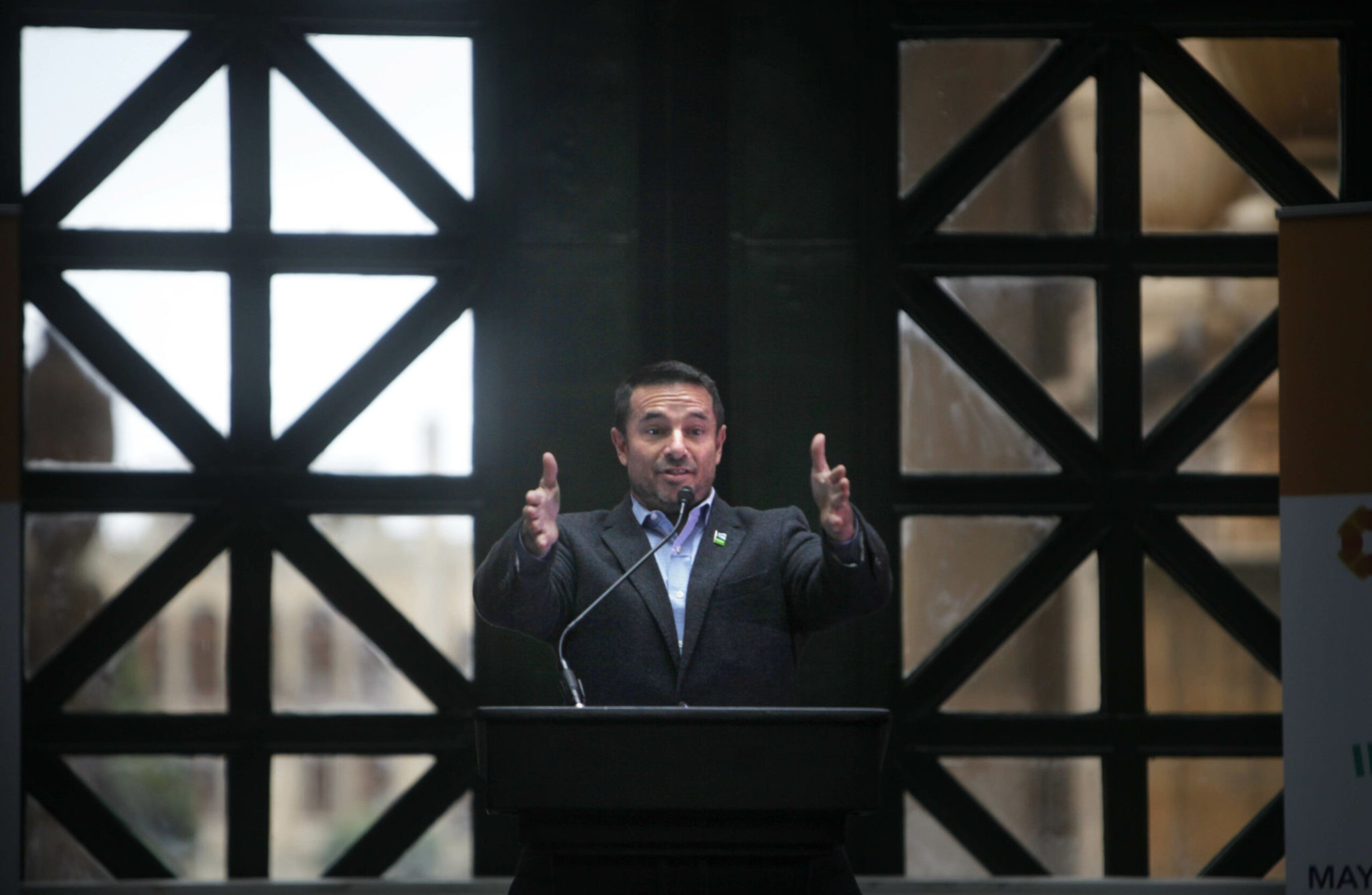

On Sept. 16, Sampson sent his letter to Ginsburg proposing a “partnership to create positive change for people and nonhuman nature.

“What if we could collectively catalyze an effort to dramatically boost the health of integrated communities of humans and nonhuman nature, all the while reimagining a world class city and inspiring others to do the same?” Sampson wrote.

For Ginsburg—who characterized San Francisco’s efforts to reduce the impact of automobiles “an example of regenerating the natural world”—the stark juxtaposition of Cal Academy’s posture on these measures made its environmental rhetoric unconvincing.

“Regenerating San Francisco’s natural world is a big, bold effort that requires vision, collaboration and sacrifice,” he said, lamenting Cal Academy’s “regrettable lack of leadership towards permanently reducing car traffic, emissions and danger to pedestrians and bicyclists from JFK, which are all contributing impediments to regenerating the natural world.”