It was around midnight on a spring day in 1989 when two carloads of men sprayed bullets into a crowd of young people hanging out in front of the Bayview Opera House, wounding nine and killing two.

The shootings in San Francisco’s historically African American neighborhood shocked the city and nation, with one emblematic newspaper photo showing SF school board member Joanne Miller consoling a sobbing neighbor whose 20-year-old daughter Roshawn Johnson was among the murdered.

“Me and her brother were the same age. We used to play in the streets together—kickball and everything else. And he was one of my first boyfriends,” said Miller’s daughter, Lena, when asked about the incident three decades later. “That was the beginning. That was the beginning of hell.”

Inspired by the violence and despair accompanying America’s crack cocaine explosion, Lena Miller would go on to found a series of charities based on her ideas about the role of trauma in African American communities.

“I was determined to go out into the world to find the ‘medicine’ to heal my community,” she once explained in an autobiographical essay.

What unfolded was a complex, often successful and sometimes confounding career in which Miller, a white woman, formed an identity firmly rooted in the African American community. Her career along the way was nurtured by a public official who was recently imprisoned on corruption charges unrelated to Miller’s work.

Miller’s efforts are premised on ideas about the psychology of violent criminals, and have generated controversy amid accusations of harassment and assault by her workers (opens in new tab), which she and her staff say is part of a bogus narrative meant to falsely villainize them. Miller includes in this category The Standard’s story about how the shooting of an Urban Alchemy employee raised questions about the company’s role providing unlicensed private security services.

She’s won fans as a tireless social entrepreneur, entrusted with helping to keep the peace in San Francisco’s Downtown neighborhoods while offering jobs to people for whom full-time employment might have seemed out of reach.

Today, Miller is executive director of Urban Alchemy, a fast-growing nonprofit organization at the nexus of public safety and homelessness. With the slogan “transforming the energy in traumatized urban spaces,” Urban Alchemy employs former long-term offenders Miller has described (opens in new tab) as people convicted of “murder and attempted murder.”

Mayor London Breed recently made Urban Alchemy a bedrock of her strategy to address Downtown homelessness and fallout from the pandemic jobs collapse. After starting with a $36,000 budget in 2018, Miller now oversees $62 million in contracts in San Francisco alone. She also runs operations in a half-dozen cities including Austin, which allocated $4 million for Urban Alchemy to run its downtown homeless shelter.

More recently, Urban Alchemy was selected for a $2.5 million contract to replace police in responding to 911 calls relating to homelessness, the Department of Emergency Management told The Standard in a Jan. 31 statement. The idea is to eliminate possible scenarios for police abuse, free up officers for crimes more serious than loitering and do a better job channeling homeless people to city services such as shelters.

Miller’s philosophy on working with homeless people is tailored for these types of tasks. She believes that extended time in prison enhances emotional intelligence because inmates’ survival depends upon becoming acutely sensitive to social cues. She says this makes Urban Alchemy’s ex-convict workers better at interacting with people suffering the types of emotional wounds accompanying poverty, violence or addiction.

This is only the beginning for Miller, who wants to expand her reach nationwide and help other cities set up Urban Alchemy-like organizations of their own.

A Persistent Identity Question

The topic of her race has long been a sore point for Miller, she said in an interview. She sometimes speaks in African American Vernacular English. And she often references her “community” in conversations about poverty and violence in the historically African American Hunters Point.

“She’s a white female,” said Kevin Williams, who mentored Miller more than two decades ago at a youth nonprofit called the San Francisco Senators. “But she has identified with being Black.”

Miller has served on panels such as KQED’s “Bay Area African-Americans Examine ‘State of the Race,’” the San Francisco Police Department’s African American Advisory Forum, and the East Bay Community Foundation’s “Moving Black-Led Organizations From Crisis to Change.”

But Miller takes umbrage at the idea that any of this is noteworthy. “That’s the first place everybody fucking goes with me when they try to diminish me to dehumanize me and make me small,” she said. “This is the community I was raised in. This is the school I was raised in, and this is what my peers did. I didn’t know anything else. I didn’t have a choice. I’m not trying to black-fish. I’m not trying to pass. I am not the next Rachel Dolezal (opens in new tab),” the former Washington state NAACP leader who pretended to be Black.

Linguist Taylor Jones, (opens in new tab) who listened to Miller’s comments on the KQED panel, said her manner of speaking is that of somebody who grew up in an African American community, and does not sound like an artifice.

Miller’s ex-husband Harold Dale, who is African American, recalls that indeed being her authentic self.

“It was surprising to me when I first met her, when I thought she was faking being Black,” said Dale, who now works at a wastewater plant in Shreveport, Louisiana. “It turned out she really and truly has got the heart of a Black person. And I think that came up when she grew up in the Bayview.”

What Dale remembers most, however, is how driven she was. “I saw how ambitious she was in trying to help people,” he said. “She was not just trying to help a few people. She wanted to help a lot of people.”

The Backstory

Miller was born in Alameda County in 1972. When she was 2, her parents moved to San Francisco and lived in a row house (opens in new tab) the family bought in San Francisco’s Silver Terrace, a hillside neighborhood between Potrero Hill and Hunters Point.

The Millers quickly gained prominence in their new hometown.

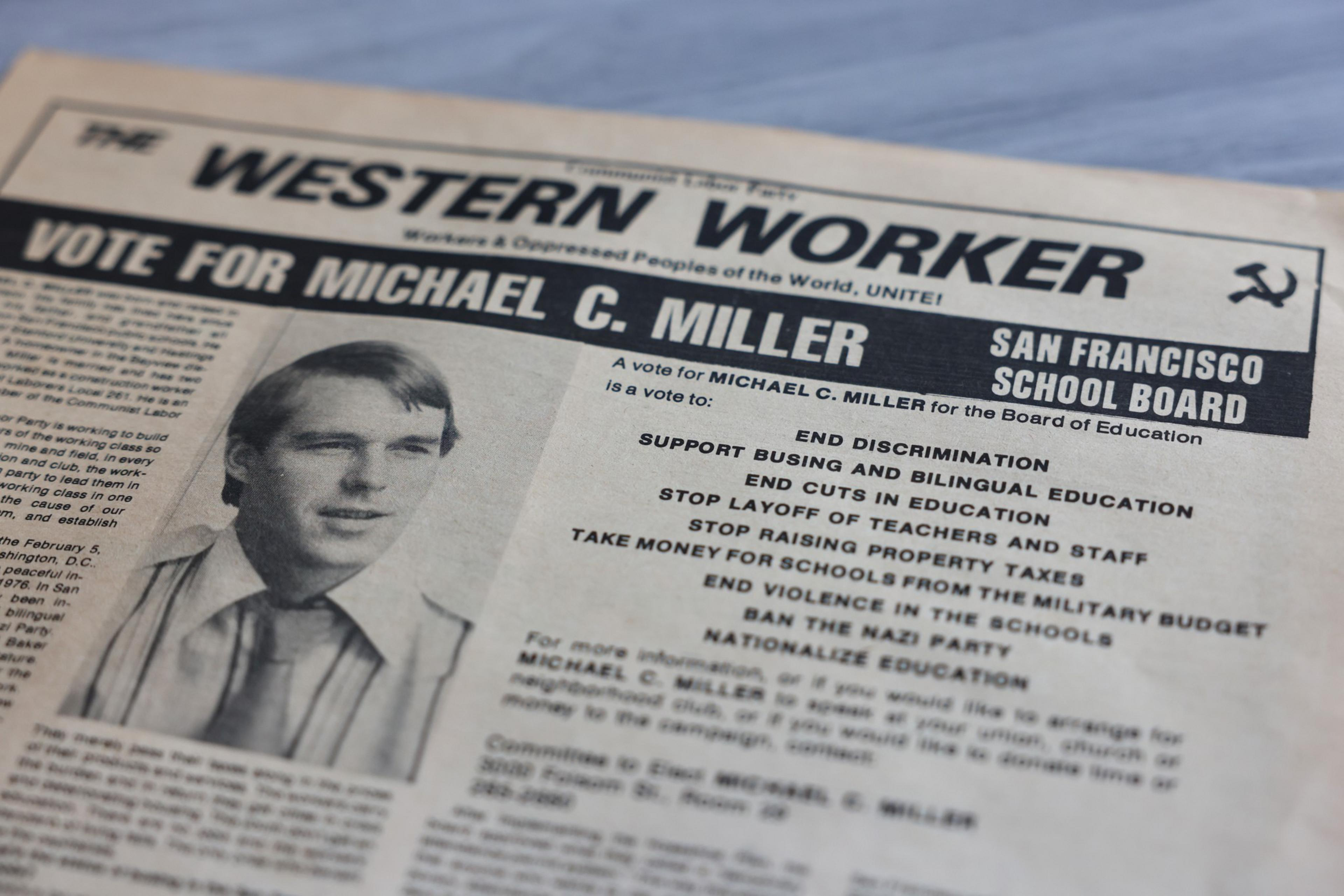

In 1976, Lena’s father Michael—a graduate of Stanford University and Hastings law school—represented the Communist Labor Party as a candidate for the San Francisco Board of Education. He was featured on the cover of the party’s newspaper. The 17,000 (opens in new tab) votes he earned was impressive for an avowed Communist, but not enough to win.

Miller said she came to see her dad’s activism as less useful than directly working with people in need.

“One day, I told my dad, ‘You’re standing out there handing out newspapers like a fool. People are laughing,’” she said. “And that day he quit.”

Her mother Joanne—a UC Berkeley graduate who now has a masters from San Francisco State and a Ph.D. from Pepperdine University—made her own run for the school board in 1984, reportedly at the urging of her daughter Lena (opens in new tab), then 12, and son Ryan, 9. Lena Miller says she remembers nothing of the sort, saying it must have been merely the version of events her mother shared with a reporter.

Joanne Miller won, became board president and was part of a dominant middle-of-the-road coalition the press dubbed “the three white ladies (opens in new tab).”

By her second term, she’d become estranged (opens in new tab) from her husband. Lena later wrote in a personal essay (opens in new tab) about how that was “a time when my family’s stability was undergoing great destruction.”

Lena Miller spent much of her teen years at friends’ houses where, Miller wrote, she “was made to feel like part of the family, giving me a much needed feeling of connectedness.”

The violence that exploded in Bayview-Hunters Point during the 1980s and ’90s led Miller to seek refuge in the coastal redwood forests of UC Santa Cruz, she said, later transferring to UC Berkeley. She married Dale, who had been a neighbor since she was a teenager, when they were in their early 20s, her ex-husband recalls.

“I had the best time I ever had with her. But we grew apart,” recalls Dale, with whom Miller had two children. “I just couldn’t keep up with her, basically.”

Career Beginnings

Lena Miller earned a masters degree in social work at SF State and tutored high school students through the nonprofit San Francisco Senators, where she was mentored by Williams. His day job was managing minority contracting programs at the San Francisco International Airport, where Williams helped his protege secure an internship.

Williams ended up becoming a key whistleblower aiding the FBI investigation into alleged links between Mayor Willie Brown’s allies and contracting fraud. He later sued the city claiming that he’d been fired as retaliation for his testimony (opens in new tab).

Williams said the city launched an unusually aggressive defense, recruiting Miller to provide testimony mischaracterizing his actions. He had been working partly from home because he was recovering from surgery, and had infuriated his superiors by rejecting what he believed were fraudulent submissions for special contracting status, Williams said.

Miller provided testimony suggesting Williams had improperly ordered her to sign his name on a contract under dispute. Williams characterized Miller’s testimony as misleading, and said she provided it at the behest of his superiors who had been under federal investigation.

When asked about this, Miller said she was merely asked to testify truthfully, and so she did. “He was like a mentor to me. I trusted him with everything. I mean, I was 21-22, and I couldn’t believe somebody” would do that, Miller said in the deposition (opens in new tab). The city ultimately paid Williams (opens in new tab) $120,000 plus attorney fees.

After her role at the airport, Miller was promoted to a job as special assistant to then-Mayor Willie Brown. At that time, she also worked to gain traction for an charitable organization she’d founded called Girls 2000.

This was when Miller met Mohammed Nuru, then head of the San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners (SLUG), a nonprofit which ultimately became embroiled in a scandal in which staffers claimed to have been coerced into helping favored politicians campaign for office.

The Nuru Cloud

In San Francisco, a city largely run by public-private contracts, Miller’s journey is also emblematic of the cloud left over the city’s government-funded programs by Nuru, former director of the Department of Public Works.

Nuru was just sentenced to seven years in prison on federal corruption charges for alleged schemes—with no connection to Miller—that included siphoning city resources into a house he built approximately 150 miles north of San Francisco.

The $360 million agency legitimately hires myriad private agencies to carry out its work. But the Nuru scandal, which resulted from intense Justice Department scrutiny into the San Francisco government, turned the department into a symbol of close links between what prosecutors called a “city family” of connected public and private officials.

Since the 1990s, Miller had a mutually beneficial relationship with Nuru.

In a 2010 essay (opens in new tab) promoting one of her nonprofits (opens in new tab), Miller took credit (opens in new tab)for helping Nuru become a San Francisco government official two decades ago, a perch from which Nuru signed off on millions of dollars worth of contracts funding Miller’s charities. There is no evidence Nuru’s corrupt schemes had anything to do with Miller or her charities, and The Standard found no evidence of wrongdoing associated with their connection.

“We dealt with Mohammed as a powerful man in Bayview-Hunters Point. And he was gregarious and big and full of life, and he helped people where he could. That was the extent of our relationship,” Miller said. “I couldn’t do anything illegal or unethical with the money because it would be the first thing that people would say, ‘Oh, this white girl’s in our community stealing money.’ And it was the first thing that everybody was looking for.”

Nuru allowed Girls 2000 to operate under the 501c3 nonprofit umbrella of his organization, SLUG, a common type of arrangement in which a group that hasn’t registered as charity with the IRS can still solicit tax-deductible donations in the name of a sponsoring organization. This eventually drew the attention of an anonymous whistleblower, who told the San Francisco City Attorney that SLUG “engaged in questionable transactions” with Miller’s organization.

Auditors were unable to prove or disprove that allegation because SLUG had incomplete accounting records, according to a report about the inquiry (opens in new tab). They did find evidence, however, of Nuru acting as a representative of Miller’s organization without any formal role. Miller said the audit was correct to find no wrongdoing.

While struggling to grow her nonprofit, Miller continued working days at her government job as a special assistant to then-Mayor Willie Brown. This was how Miller happened to introduce her sponsor, Nuru, to the mayor.

Impressed, Brown hired Nuru to join his administration, where Nuru served as assistant director of the Department of Public Works. He was later promoted to department head.

Once in government, Nuru urged Miller to quit her job in the Mayor’s Office and work for nonprofits full time. She co-founded a new nonprofit called Hunters Point Family, which absorbed Girls 2000. According to city records (opens in new tab), it went on to obtain $34 million in funding from the Nuru-led Public Works department, for tasks such as monitoring outdoor public toilets and cleaning up litter.

“The budget went from $6 million to $20 million,” Miller said, adding that with success came conflict.

“People’s feelings changed,” she said. “So when I get fucked-up vibes and negative vibes, I just try to go the other way. And one thing about me that I know: I know I can lay the golden egg.”

Miller took the division that had been carrying out the Public Works contracts, and launched it as a separate organization called Urban Alchemy.

Urban Alchemy got a boost when Nuru’s Public Works in 2019 sent a letter to Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, urging the city to hire the nonprofit (opens in new tab) for security and other services around Skid Row.

Nuru’s Public Works also aided Urban Alchemy by redirecting $1.5 million in cash payments negotiated with the French outdoor advertising firm JCDecaux from city coffers to Urban Alchemy to pay for restroom monitoring, according to records from the City Controller’s Office (opens in new tab).

Miller’s World Now

Today, Miller is emerging as an urban leader of potentially national stature through word of mouth.

Urban Alchemy’s latest expansion is in Portland (opens in new tab), which plans to ban homeless people from living outdoors except for in government encampments, which are slated to be overseen by Urban Alchemy.

The contracts in Portland, Los Angeles and Austin have been accompanied by fulsome endorsements from city officials. U.S. mayors have been telling each other about the innovative work done by a group that employs ex-felons, and giving Miller a call, she said.

“The mayors call up other mayors. And they say, ‘Well, I’m going in there to see what’s going on. What’s going on? How are you dealing with the issues in Los Angeles?’ They wanted alternatives to the police. They heard about what was happening in San Francisco,” Miller said.

Urban Alchemy’s reflective-vest-wearing “ambassadors” have become ubiquitous in parts of Downtown, providing security at the Main Library and homeless encampments such as the one at Candlestick Point. The group recently signed an $18.7 million contract to run a 250-unit shelter in Lower Nob Hill.

“Our phones 40 or 50 years ago used to look like Princess phones (opens in new tab), if we were lucky; that was the nice stuff. Now they look like this,” Miller said, holding up her smartphone. “What we’ve done is we’ve created the iPhone for social service: We put in the science; we’ll put in the common sense. And we put the people in,” Miller said.