It’s no secret that Downtown San Francisco has struggled in recent years: 25 million square feet of commercial space sits vacant, tech companies have shuttered their brick-and-mortar offices and the news of layoffs is relentless.

Now, a report shows that San Francisco’s famously flexible work-from-home policies may have cost the city billions. Workers in San Francisco are spending roughly $3,567 less per year apiece on things like entertainment, dining and shopping near their places of work.

The cause? A 34.7% reduction in its in-person workforce, according to new data (opens in new tab) from the WFH Research Group.

READ MORE: Surreal Moment as Downtown SF Office Not Touched Since Pandemic Is Cleared Out

In total, The Standard estimates the yearly spending loss for San Francisco’s entire residential and commuter workforce could top $2.9 billion dollars.

The Standard calculated the total by multiplying the per-worker spending loss ($3,567) by the estimated 820,000 residents and Bay Area commuters (opens in new tab) who work in San Francisco, based on data provided by the American Community Survey and the SF Controller’s Office. (SF workers under 20 and over 60 years old are excluded to better approximate the sampling parameters of the WFH Research study.)

WFH Research showed that reduced consumer spending near workplaces most severely affects cities with longer commutes, greater Covid restrictions and a higher proportion of white-collar workers—all factors prominent in the Bay Area economy, which would contribute to an even bigger economic loss from remote work.

Rising Remote Work, Declining Inner City Economies

The effects of the pandemic are well-documented, with many local business owners lamenting the loss of workers who once patronized Downtown restaurants and shops. But this new study lays bare how much of a fiscal impact pandemic work styles have had on Bay Area communities, a region heavily dependent on the WFH-friendly tech industry.

Between 2019 and 2021, the number of people working from home (opens in new tab) in the U.S. tripled, from 6% to 18%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In San Francisco, that statistic increased sevenfold, with 46% of employees clocking in from home in 2021.

Increased workplace flexibility in 2020 and 2021 was largely due to pandemic conditions. But as cities open up and San Francisco plans to end its Covid public health emergency declaration, a return to in-person work lags far behind. The city’s beleaguered Downtown, in particular, has taken the biggest economic blow from remote work and remains a near ghost town.

READ MORE: Mayor London Breed’s State of the City Address in 3 Minutes

The result? San Franciscans are spending much less on things like meals, shopping and entertainment near their workplaces every year. Other major metropolitan areas documented even steeper drops in consumer spending: New Yorkers spent $4,661 less per person yearly, sucking over $12 billion in spending (opens in new tab) from the financial powerhouse.

But data doesn’t tell the whole story, and researchers warn that the region may be losing far more money than WFH data shows, simply because many workers are no longer based in the Bay Area.

“We asked people about their spending habits before the pandemic back in 2020, but we are looking at people whose jobs are currently based in the Bay Area,” said Jose Maria Barrero, researcher at the WFH group and professor of finance at Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México. “It might be that the Bay Area looks like it has a smaller reduction [in consumer spending] than it actually has because these people have already left. When the person answers the survey, they already say, ‘My job is somewhere else.’”

The Bay Area lost more than 217,000 people since 2020, and San Francisco proper outpaced the broader region with a 4.4% overall population drop during that period versus 2.1% across the entire Bay.

“Major population and migration shifts in either direction can have large ramifications in the area’s economy, housing markets, public services, quality of life and even its ecology,” said Patrick Carlisle, a market analyst with Compass Real Estate.

What this means for San Francisco is fewer employees looking for a good coffee meeting spot, empty restaurants and lagging home sales in regions that once served as the city’s workplace center.

‘The Donut Effect’

City Economist Ted Egan warns that reduced spending around workplaces, and particularly in the city’s downtown corridor, could have been redistributed to other parts of the city, or regions in the Bay.

“The [WFH Research Group] is just trying to measure the change in spending near workplaces,” Egan said. “[WFH] is estimating that each worker will spend less near their workplace, in proportion to how much they are working at home. That income will of course be available for spending on other things within the region.”

Many workers might also be trickling out to surrounding regions, bolstering their economies in turn. Compass data found that the majority of people moving out of county in the Bay Area are moving to adjacent counties (opens in new tab), often those that are more affordable and less densely populated.

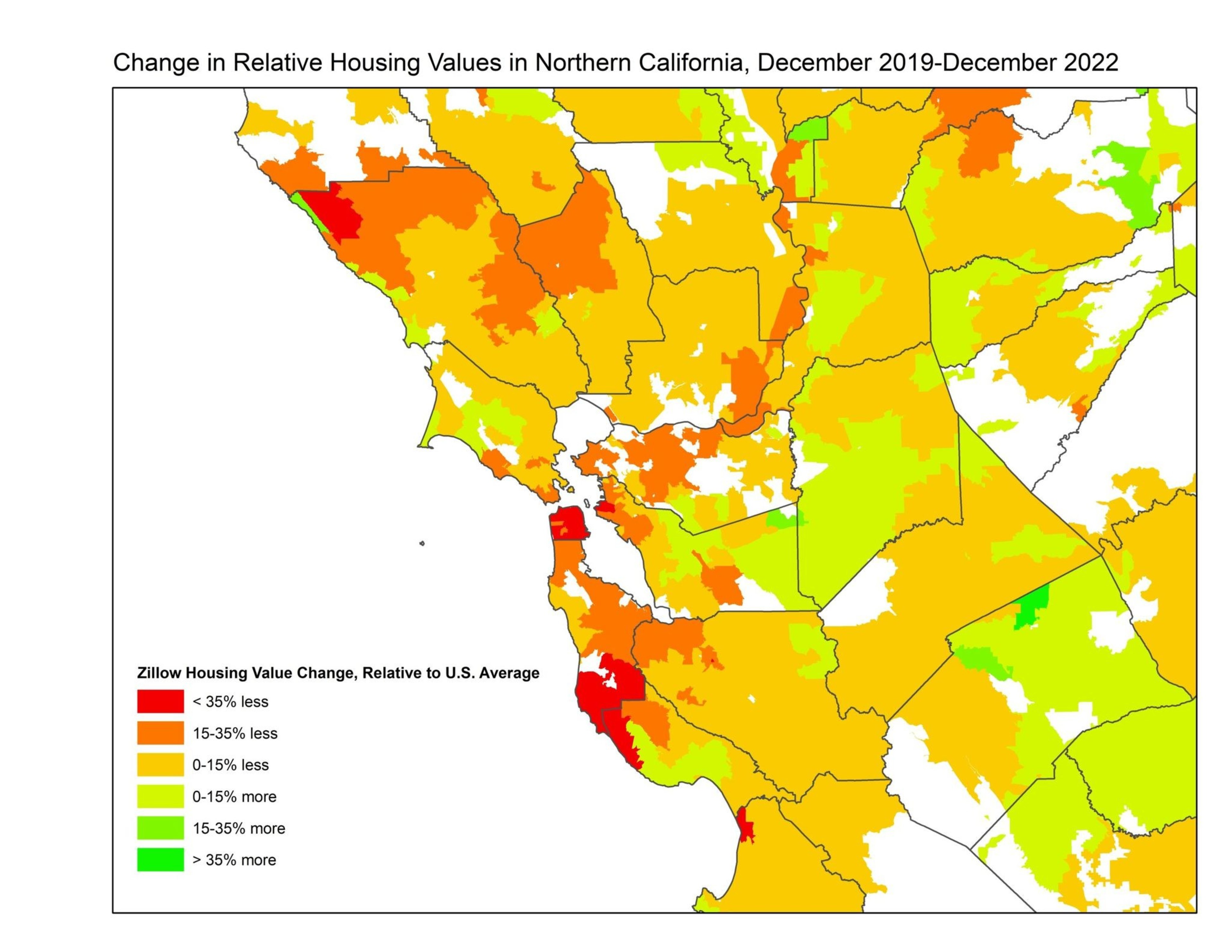

Called the “Donut Effect (opens in new tab)” by Stanford University economists, many households and businesses relocated from central business districts (economist-speak for city centers) to lower-density suburban ZIP codes in 2020 and 2021. The pandemic effectively hollowed out city centers like San Francisco, lowering rental rates and wreaking havoc on city finances through loss of taxes.

“Economists see [this pattern] in rental prices,” Barrero said. “My sense is that the Bay Area is probably going to have a bigger donut effect than other cities because it’s heavily tech-dominated and tech has a lot more working from home than, say, finance or consulting, or law. And second, I think it’s just kind of very nice to live in the Bay Area, and not in San Francisco. It’s kind of a domino effect.”