When San Francisco Supervisor Dean Preston ran for reelection in 2020, he changed his name on the ballot—not his English one, but his Chinese identity.

Preston, who is of German descent, requested to appear on the ballot as “潘正義,” which means “Justice Pan” in Chinese. Previously, he was “迪恩‧普瑞斯頓 (opens in new tab)” on the ballot, a long and transliteration-based Chinese name.

An outspoken advocate for tenants’ rights and other progressive-leaning causes, Preston’s choice of “Justice” as his name was perhaps obvious—if a bit superhero-esque. “Pan,” on the other hand, is simply a Chinese surname that starts with the letter P.

“I think that [my Chinese name’s] relevance has increased,” Preston told The Standard. “There are a lot of Asian residents in my district now.”

Since redistricting drew the Tenderloin into Preston’s district in 2022, approximately 20% of his constituents are Asian American. Citywide, Chinese Americans comprise approximately one-fourth of the population. This demographic fact leads to local election ballots being, by default, bilingual in English and Chinese and starting from 1999 (opens in new tab), candidates will appear with Chinese names.

Traditionally, political candidates who are not of Chinese ancestry have appeared on the ballot with a Chinese name based on their English names’ phonetic transliteration—many of these could be a long and awkward moniker of five, six or more characters, written with a dot between the given name and surname (something never done with typical Chinese names).

But now, aspiring officeholders are being much more deliberate about selecting an “authentic” Chinese name—normally three characters, with a Chinese surname first, and two characters as given name.

For monolingual Chinese voters, a three-character Chinese name can be easier to remember than a longer, transliterated name. Having a Chinese name that rolls off the tongue can help a candidate boost their name recognition in Chinese media.

Everybody’s Doing It

Vice President Kamala Harris appears to be one of the first to start this trend when she first ran for San Francisco district attorney in 2003, according to Chinese-language media. Harris ditched the transliteration-based name 哈里斯 (“ha lay si”) and chose 賀錦麗 (“ho gum lai”) instead. To Cantonese speakers’ ears, the new appellation had a more celebratory and positive ring (the surname Ho, 賀, means “celebrate”), while Gum-Lai has a feminine quality (錦麗 means “beautiful”).

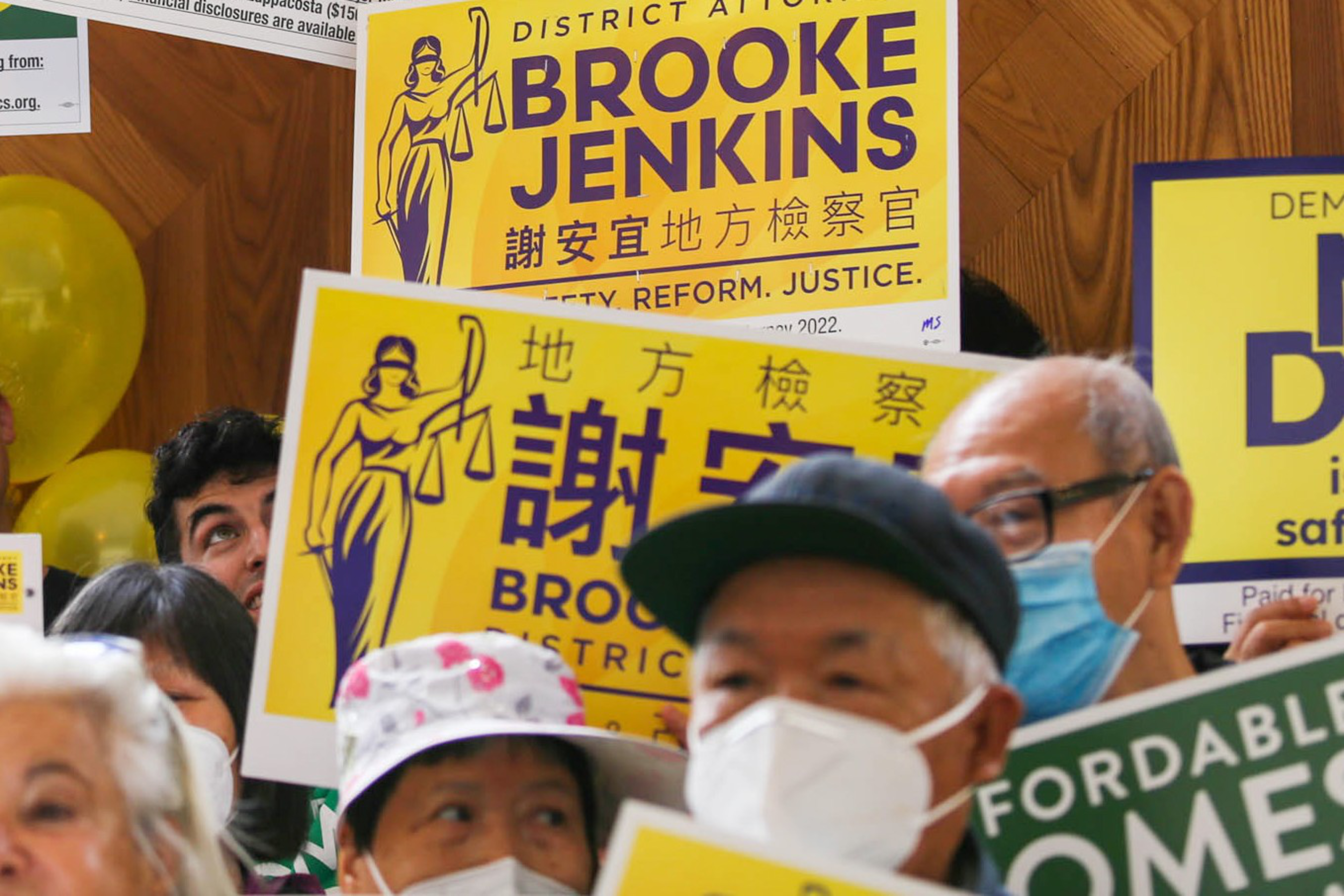

Candidates for San Francisco’s school board, City College board and the BART board are no exception—having a three-character Chinese name is now the norm.

It’s hard to measure the actual impact of an “authentic” Chinese name on the ballot, because there is no official data on how many Chinese-reading voters call San Francisco home. But according to U.S. Census data, about 184,000 people of Chinese descent live in San Francisco, and among them, 118,000 are foreign-born. Presumably, a large number of those immigrants can read Chinese—and some American-born Chinese can, too.

Department of Elections data shows that 95% of San Francisco voters receive the English and Chinese bilingual ballot. The other 5% requested non-English, non-Chinese language ballots like Spanish or Tagalog. About 30,000 voters requested the Chinese-language Voter Information Pamphlet (選民資料手冊), about 6% of total voters.

Who Gets To Name You?

Karen Gee, an immigrant from Guangzhou who lives in San Francisco’s Portola neighborhood, is the go-to name-giver for many progressive political candidates in the city.

She has bestowed Chinese names on elected officials including State Assemblyman Matt Haney and Supervisor Shamann Walton. Gee’s daughter, Natalie, is the chief of staff for Walton.

Gee said that she loves Chinese literature, and selecting Chinese names for others is a way for her to share the beautiful Chinese language and culture.

Gee explained that she chose Haney’s Chinese name, 楊馳馬, because the second two characters mean “running horse,” hinting that he would run like a horse in the race and win. And, the pronunciation for horse is “ma,” which is close in sound to his first name, Matt.

Natalie Gee, who’s fluent in Chinese, has also given out some Chinese names as well. Preston’s “Justice Pan,” for example, was her creation.

Mayor London Breed doesn’t have an “authentic” Chinese name but a five-character, phonetic, transliteration-based name. She has two characters, 倫敦, that approximate the sound of “London” followed by three characters, 布里德, that come close to the sound of “Breed” or “bow lay dak.” This major difference is that this type of name doesn’t have a typical Chinese surname like Chan, Zhang or Ho.

Breed previously said that she grew up with Chinese American friends who speak Cantonese, and her high school friend gave her the name. Aaron Peskin, president of the Board of Supervisors, also has gone for a phonetic transliterated name, 佩斯金 (pui see gum).

Election Rules

When a candidate submits a form to run for office in San Francisco, they have to answer a question: Do you want the Department of Elections to make you a Chinese name, or do you have one already?

Catherine Lee, a manager of the voter information division at the department, is the de facto gatekeeper, tasked with reviewing candidates’ submissions. An immigrant from Hong Kong and a former news anchor, Lee speaks fluent Cantonese.

She has a few rules. The submitted names have to be in traditional Chinese, which is used in Hong Kong, Taiwan and some overseas Chinese communities while mainland China uses simplified Chinese. They cannot be the same as historic figures or celebrities. They cannot lead to ambiguity or become too promotional.

Lee added that she likes to ask candidates to provide some examples of Chinese media coverage showing the candidate’s Chinese name has been circulated by the press.

In 2022, when former police commissioner John Hamasaki ran for district attorney, he wrote his Chinese name on the filing forms (opens in new tab) and attached an article from the Sing Tao Daily proving that’s how Chinese media referred to him.

But in Preston’s case, his Chinese name initially met some challenges. When he ran for supervisor in 2019, the name “Justice Pan” was rejected (opens in new tab) on the grounds that it was too positive, and the department considered it unfair to his opponents. Plus, Preston had never used it before. However, Preston won the election and continued to use Justice Pan in the Chinese press, so election officials exempted him, and let him use it on the 2020 ballot.

In 2019, Assemblymember Evan Low authored legislation (opens in new tab) to regulate Chinese translations on California’s statewide ballots. The law mandates that candidates use transliteration-based names unless they can prove that they were born with a character-based name or have been using such an “authentic” style Chinese name for at least two years.

San Francisco’s Department of Elections has rules (opens in new tab) that slightly differ from Low’s legislation and has insisted his law doesn’t apply to local races, which means candidates do not need to prove that two-year usage. The City Attorney’s Office didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Supervisor Connie Chan, an immigrant from Hong Kong, said she’s considering actions on the board to implement Low’s bill at the local level.

“We need to recognize Asian heritage,” Chan said, “and a person’s name indicates who they are and their heritage.”

Chan, as the only Chinese American supervisor on the board, slammed some candidates for trying to trick voters with their Chinese names.

“We see that there are times where candidates are using the Chinese name as a way to mislead voters to let them think that they are of Chinese descent,” she told The Standard.

Voting for a Chinese Name?

Nevertheless, Chan has bestowed an “authentic” Chinese name on one of her colleagues: Supervisor Matt Dorsey, or 麥德誠. She cited Dorsey’s long history of public service as a communication expert and his connections with Chinese-language media as the reason she did it for him.

Chinese American identity politics have become far more complicated in San Francisco politics in recent years. By unseating Supervisor Gordon Mar last year in a race that surprised many observers, Joel Engardio, a white man, also ended a long, unbroken chain of Chinese American supervisors in the Sunset District. Many Chinese American voters said that they used to vote for whomever had an Asian name, but now they take other factors into consideration (opens in new tab).

Even so, many potential candidates have decided to pursue a Chinese name, too. Trevor Chandler, who announced a run for District 9 supervisor in the 2024 election, also got himself a brand-new Chinese name, 陳澤維, which is pronounced “chun zak wai” in Cantonese, picking the surname Chan because it’s similar to “Chandler” and “zak wai” because it’s close to “Trevor.”

Another potential candidate for that race, Roberto Hernandez, confirmed with The Standard that his new Chinese name is 何保行; the last two characters mean “protect walking.”

Jackie Fielder, who has also mulled a run for District 9, said she’s had a Chinese name since 2020. That year, Fielder ran a high-profile campaign against state Sen. Scott Wiener, and the local election department at that time refused to print her submitted Chinese name, 福天亮 (fuk tin leung), because she hadn’t used it for two years for a state office race.

But for 2024, she plans to submit that name again for the ballot, because the name connects to her Native American name, “nagsháawi (opens in new tab).” An enrolled member of the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes, she is ethnically Hidatsa and chose to honor that heritage.

“It means ‘dawn’ or ‘daybreak,’” Fielder said of both her native name and her Chinese name, 天亮. “It shows a big part of who I am.”