An Old Navy at a mall in New Hampshire transformed (opens in new tab) into the All-Star Pickleball Club last December and is a draw for players from as far as Massachusetts. Pickleball America leased over 80,000 square feet in what used to be a former Saks Off 5th location in Connecticut. Outside of St. Louis, pickleball courts are taking over (opens in new tab) a former Bed Bath & Beyond.

There’s even a startup—appropriately titled Picklemall (opens in new tab)—dedicated exclusively to transforming shuttered shopping areas nationwide into thriving sport courts.

Could the same thing happen at the recently collapsed Westfield San Francisco Centre? Probably not—but not for a lack of local love for the ascendant sport, which has exploded in popularity in recent years.

The San Francisco Pickleball Community (opens in new tab) emerged around five years ago as a small cadre of about two dozen active players, but it’s since grown to more than 2,000. And it’s only poised to get bigger.

The cross between tennis and pingpong is coming to Oracle Park for a four-day festival (opens in new tab) in July, with courts plotted directly on the ballfield. The price tag (opens in new tab) is a whopping $1,500 per group per session.

“It’s just crazy,” said Ward Naughton, a volunteer with the San Francisco Pickleball Community advocacy group, of the cost. “But it shows you what’s happening to the sport.”

Our own Golden State Warrior Draymond Green has purchased, along with other investors, a Major League Pickleball (opens in new tab) team. New courts have opened (opens in new tab) at the Louis Sutter Playground and the Lisa & Douglas Goldman Tennis Center (opens in new tab), and the sport has more than doubled in growth (opens in new tab) nationally over the past three years.

“There’s a low barrier to entry,” San Francisco pickleball player Geoff August said, explaining the sport’s appeal. “And there’s also the social aspect.”

There are now more than 36 million pickleball players (opens in new tab) in the U.S. and—despite some associating the sport with seniors—the largest percentage of players (opens in new tab) is in the age bracket of 18-34, according to the organization Pickleheads (opens in new tab).

The enthusiasm for the sport is so rabid that some are even saying its feisty, democratic spirit could save the soul of America (opens in new tab).

Retail Conversions—Potential or Pipe Dream?

As the demand for pickleball courts grows ever more intense—at times leading to fiery clashes with tennis players—the city could potentially solve two problems at once by converting shuttered retail space into recreation hubs.

Sounds too good to be true? It may not be.

A report by JLL (opens in new tab), an organization that tracks trends in retail spaces, says pickleball court developers are targeting malls for expansion—and so far it’s been a success nationally.

“It’s a no-brainer for any space that’s underutilized,” said Brandon Mackie, co-founder of Pickleheads. “Pickleball is consistently outstripping the supply in almost every market that we track.”

The sport has leaped outside the boundaries of retirement communities where it first caught on and is now gaining steam most quickly in dense, urban metro areas—where a lot of younger people live.

Pickleball’s popularity is expanding at a galloping pace for two main reasons, according to Mackie: the ease of play and the social component. You can learn the game in about 10 minutes, and players rotate partners and share court space.

“For a lot of people, it’s not even really a sport,” Mackie said. “It’s a social outlet.”

According to the report, it’s part of a larger trend in which consumers are prioritizing gathering over shopping. After years of pandemic-related isolation, people are craving experiences—not things.

That has led to growth in spending on travel and its related costs, like accommodation, performing arts and amusement parks.

But a space like Nordstrom—which has pulled out of the ailing Westfield mall—could be tricky to convert. Warehouses, with their open space and lack of columns, are easier (opens in new tab) to make into courts.

“We already tried,” Jonathan Padilla said of converting retail spaces in San Francisco. The certified pickleball coach is part of the Golden Gate Pickleball Association, the first advocacy group for the sport in San Francisco. “It’s a zoning issue, and the city won’t allow it.”

It’s a shame, according to Padilla, because there are a lot of great spaces that could easily be converted to pickleball courts. The demand for new courts is high—but so is the price per square foot in San Francisco.

“As much as you hear those stories [about pickleball in Westfield mall], it would be very hard to come in,” he said.

There’s also the question of money. While the idea of pickleball in empty retail spaces feels like a perfect solution, it has to pencil out. As it stands now, pickleball is not a huge revenue generator. Most players are looking for courts where they can play for free and even paid courts, like the ones in Golden Gate Park, cost under $20 an hour, split among four people.

Parking and safety are additional concerns—two big unknowns when it comes to Downtown spaces.

“As a panacea for retail, it would be hard,” said Naughton of the San Francisco Pickleball Community.

None of the vacant retail spaces The Standard contacted responded to requests for comment on the potential of pickleball conversions.

While it may be unlikely for pickleball alone to bring in the type of revenue retail does, there is another option—pickleball-playing clubs that combine food and drink with sport in entertainment complexes. It’s been successfully modeled with chains like Chicken N Pickle (opens in new tab), which has locations throughout the Southwest and Midwest as well as a new chain launching in Alabama in 2024 called Camp Pickle (opens in new tab), which will eventually have 10 locations.

Yet even with the increased revenue stream such an entertainment-sport complex would offer—think of the rabid success of Topgolf (opens in new tab), which combines nightlife with golf and makes it approachable for beginners—there would still be challenges to create something similar in San Francisco, given the city’s many use restrictions.

Growing Pains

With the permanent pickleball courts under construction at Larsen Playground and closed at Stern Grove, the only permanent, dedicated and free courts for pickleball are next to Louis Sutter Playground in the Excelsior’s McLaren Park.

The pickleball courts at Presidio Wall—the busiest and buzziest of all in the city—are double-lined onto tennis courts and are not permanent. The wait there for a 15-minute game can be upward of 40 minutes for a court on weekends, according to Naughton.

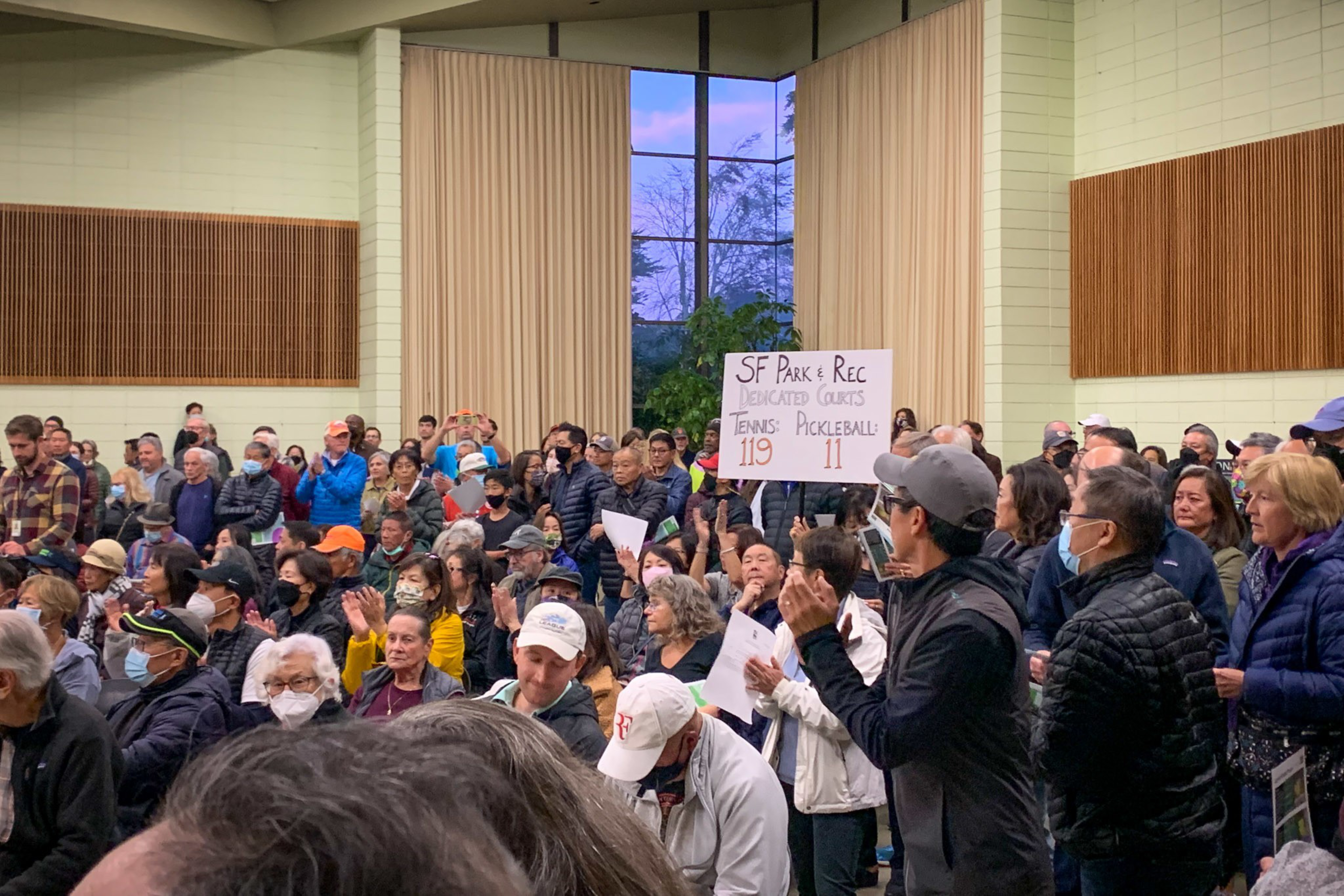

“You’ll have 100 or 200 people show up,” Naughton said. Some pickleball players feel frustrated that while there are many tennis courts in the city—110 by Padilla’s count—there are relatively few places to play pickleball (there are also pay-to-play courts in Golden Gate Park).

The Bay Club and the Olympic Club have added pickleball courts, but you have to be a paying member. Padilla facilitated the addition of courts at the Bay Club, where he brought in around 100 new members thanks to the addition of dedicated courts.

Padilla is also organizing indoor pickleball at the Palace of Fine Arts, which has its soft launch at the end of June and will open to the public (opens in new tab) in the beginning of July. While the paid options for playing pickleball are multiplying, many enthusiasts would like to see more park spaces dedicated to the sport.

“The city is falling behind,” said pickleball player Suzette Safdie. “Rec and Park is not moving fast enough because the tennis coalition is opposing converting any more courts to pickleball courts, even though some of the tennis courts are never used.”

While tennis players have reported that it’s also difficult for them to reserve courts in the city, Padilla—who plays both tennis and pickleball—says that’s the case only for certain areas.

“The demand is high for popular tennis courts,” Padilla said. “But there are many that are underutilized.”

The space of two tennis courts could be converted into as many as eight pickleball courts, which would end up servicing up to 32 players instead of only four (eight if playing doubles tennis).

“It’s a much better utilization of public facilities,” Naughton said.

The intense demand for the sport, coupled with the low supply of courts can lead to tensions.

“We’ve had an ongoing debate with the city that the sport is growing, and there’s a need for more dedicated pickleball-only courts,” Naughton said. “It can create conflict with the tennis community.”

Yet many pickleball enthusiasts also play tennis and argue that the problem is not so much between the players of the two sports, but with the Recreation and Park Department.

“It’s the city not adapting quickly enough,” Padilla said.

Yet from its perspective, Rec and Parks is doing the best it can to keep up with demand.

Tamara Aparton, a spokesperson for Rec and Parks, points to the achievements the department has made (opens in new tab) in trying to meet the demand for pickleball. While in 2018 there were only 12 courts to play pickleball in the city, there are now more than 60 (59 outdoor and 6 indoor). When Larsen opens (projected for this fall), there will be an additional 19 dedicated courts.

“Far, far more pickleball spaces have been created over the past five years in San Francisco than for any other sport,” Aparton said.

Every tennis court repaving happening in the city will now include dual lines for pickleball, Aparton said, and there are also pickleball nets that can be rolled into place at several sites.

“Expanding pickleball has been a big priority while also keeping in mind we must balance the needs of all our parkgoers,” Aparton said, who pointed out that tennis also experienced growth during the pandemic.

“It’s a compromise,” Padilla said.