For more than a decade, struggling taxi drivers have blamed Uber and Lyft for siphoning off their customers and making a difficult living even harder.

But now traditional cab drivers and contractors who work for ride-hailing apps have united against a common enemy—taxis without any drivers at all.

By November 2022, officials granted so-called robotaxis operated by Waymo, owned by Google’s parent company, and General Motors-owned Cruise permission to serve paying passengers. These robotaxi services have continued to expand rapidly despite concerns about the safety record of driverless vehicles. Autonomous vehicles have prompted outrage by interrupting public emergencies, rolling over a fire hose during a major house fire and, in another instance, narrowly missing a light-rail car. Another killed a small dog.

But taxi and ride-hailing app drivers say robotaxis could have another human cost that’s largely been glossed over. They’re worried that the added competition could mean human drivers could further shrink earnings that they say have been steadily dwindling from rising costs and rate changes.

“We’re already seeing it,” said Jose Gazo, an Uber driver of seven years who added he finds himself driving longer hours to make less money. “With business going like this, we’re going to go homeless.”

This week, the California Public Utilities Commission, for the second time in a month, delayed a vote scheduled for Thursday that would have allowed autonomous vehicle companies unlimited 24/7 expansion in San Francisco. A chorus of local public safety and transit officials have called for a slowdown in their expansion plans, arguing that self-driving cars have only “met the requirements for a learner’s permit,” not a driver’s license.

Waymo responded that it has about 200 cars providing more than 10,000 rides per week with no collisions involving pedestrians or cyclists on record. A Cruise spokesperson previously touted its safety record to the Standard, noting that it “includes millions of miles driven in an extremely complex urban environment.”

Driverless Future Overhyped?

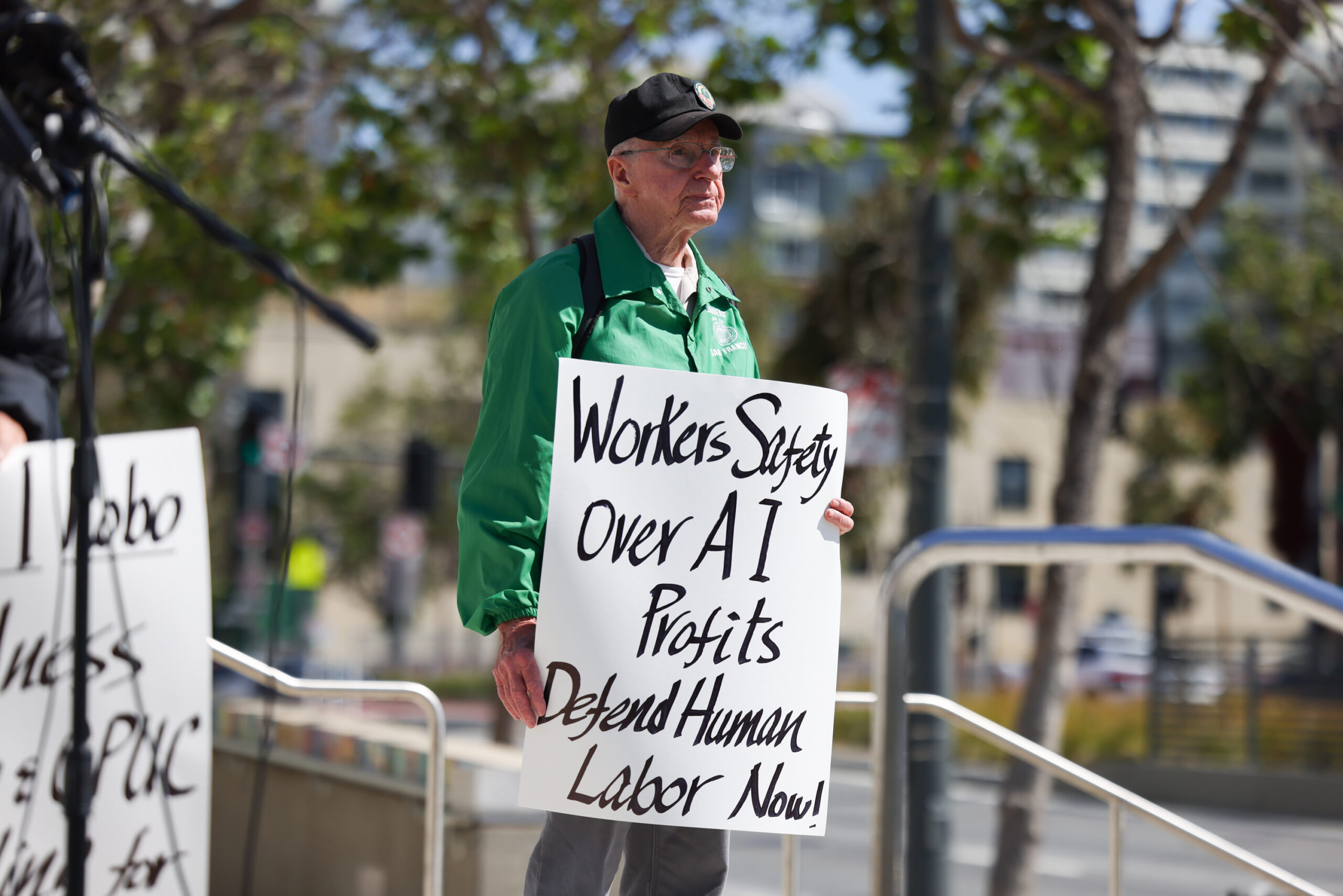

None of that has dampened the resistance among drivers against the rise of autonomous vehicles. Taxi and app-based drivers staged a protest outside the commission last month, protesting an imminent expansion of driverless cars with questions about what it means for future work.

But even if Waymo and Cruise prevail over local safety concerns, experts don’t believe robotaxis will replace human drivers. For one thing, they’re expensive to build. A ride in a Cruise car is slightly cheaper for customers than taking an Uber, but the vehicles outfitted with sensors and cameras cost much more to make than ordinary cars. In response to mounting losses, Cruise told investors in March that it would focus on cutting costs. Ford and Volkswagon pulled the plug on their joint autonomous vehicle venture last fall.

The companies are also limited by federal law, which says manufacturers are only allowed to produce 2,500 driverless cars apiece per year, though legislation to lift the cap has been proposed.

Ken Jacobs, chairman of the University of California Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education, believes visions of a driverless future have been “grossly overhyped.”

“The threat isn’t to the number of jobs; it’s to the quality of jobs,” Jacobs told The Standard. “The market left to its own is likely to come out with outcomes that … are bad for workers.”

Drivers say they are spending more time on the road but are making less from rate adjustments while still covering the cost of gas and maintenance.

The Rideshare Guy, a popular blog for gig workers, found in January that recent rate changes mean that Uber drivers are making 19%-27% less on long rides.

On the subject of rate changes, Uber said in California, drivers make median earnings of $38 per engaged hour—not accounting for idle time or driver expenses—and as of a change instituted earlier this year, drivers can now see prospective earnings before accepting rides. Lyft did not respond regarding driver earnings by publication time.

“We did not see a significant change in per-trip earnings, but we did see an increase in the number of driving hours, suggesting drivers appreciated the changes made,” said an Uber spokesperson of fare changes. “As drivers know, earnings on Uber vary as marketplace conditions change.”

Jason Munderloh, a part-time Lyft driver of nine years, said the company has made some improvements for drivers, like a setting to pick up rides only in the direction they are traveling, but overall, pay has dropped. The advent of autonomous vehicles has him looking at other possible careers, like bartending.

For San Francisco taxi drivers who took out loans for a $250,000 medallion under a program introduced in 2010, the year Uber first arrived on city streets, the prospect of making less money is especially terrifying. The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency brought in $64 million through the program, which has since seen 301 foreclosed medallions. It still has 427 paid medallions as of last week.

The owner of one of them, Brent Johnson, a San Francisco cab driver of 30 years, said with his current income, which he estimates at around minimum wage, he can only afford to pay off the interest on his medallion loan. He’s hoping for restitution, arguing that, since they’re functioning as taxis, autonomous vehicles should pay into the medallion system. But if his loan isn’t taken care of, he is bracing to default as retirement nears.

“I’m hoping for the best and preparing for the worst,” Johnson said.

There are still over 2,550 drivers with a taxi permit, according to the SFMTA. Spokesperson Stephen Chun said the agency, which has urged data collection on the safety record and environmental and economic effects of autonomous vehicles, is “confident” that taxi drivers will continue to provide critical transportation, like through the paratransit program, in the long term.

Billy Riggs, a University of San Francisco professor who studies transportation innovation, also sees a long future with a continued need for human drivers.

“If we’re honest with ourselves, it really does relate to this bigger question of the future of work, the future of cities,” Riggs said. “Transportation, right now, just highlights this.”