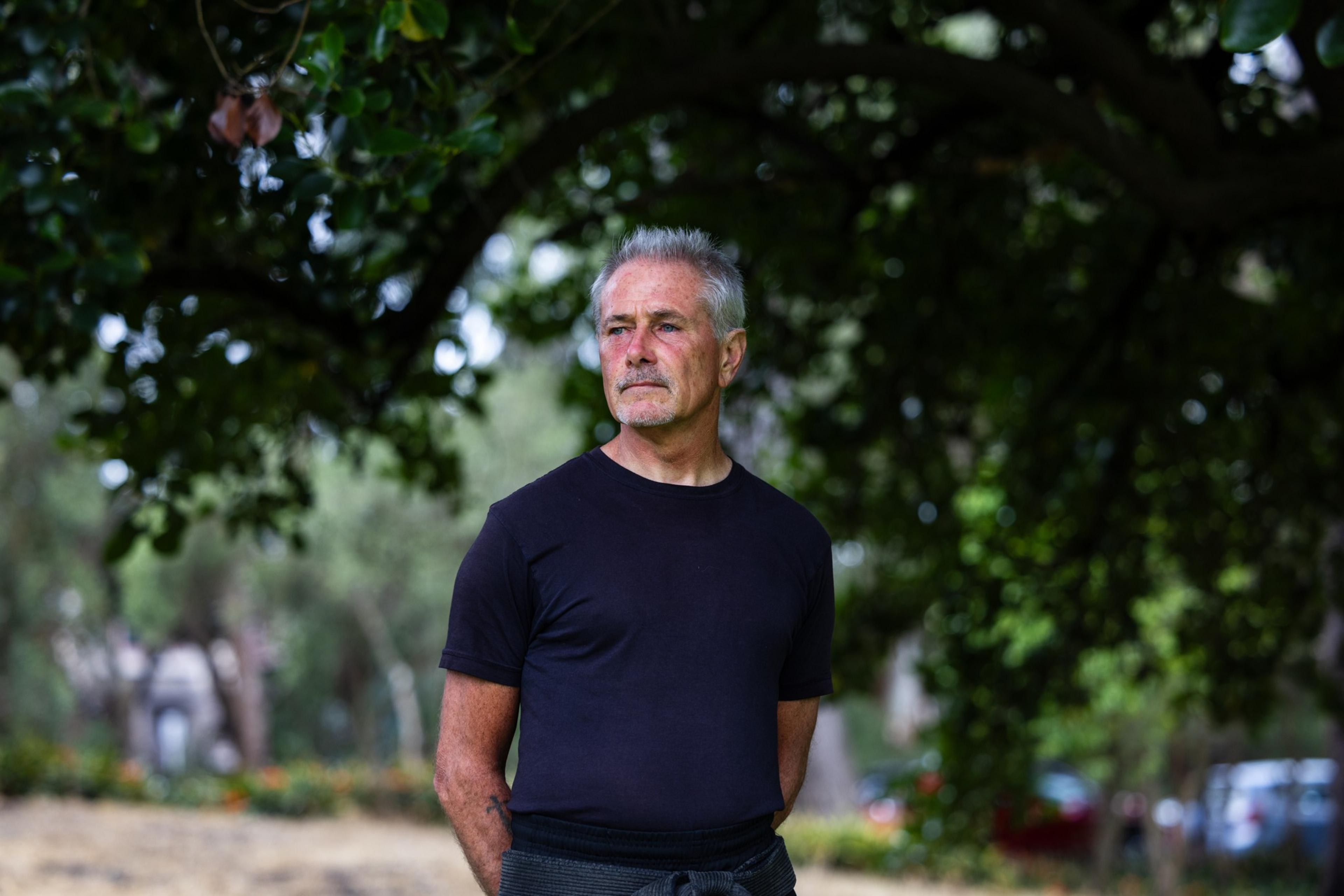

When massage therapist Kevin Hammond landed in one of San Francisco’s most state-of-the-art homeless shelters, known as a navigation center because it’s designed to help people navigate out of homelessness, he was cautiously optimistic that staff there would help him back onto his feet.

But after nearly seven months living at the facility along the Embarcadero waterfront, Hammond said he’s become increasingly desperate to leave the shelter, even toying with the idea of returning to the streets despite having saved up almost enough to afford his own place.

Hammond is not alone among shelter clients in saying the facilities aren’t designed to help people become self-sufficient. These critics say the shelters are overloaded by people in need of more help than just a bed, leading many back to the streets or from one city-funded building to the next.

They also said some shelter occupants would benefit from an environment with stricter rules and job counseling.

Hammond said that a series of bad decisions and a complicated relationship with his ex-girlfriend landed him on the street. At the shelter, he says his path back to self-sufficiency has been hampered by fights between clients and staff, rampant drug use, overdoses and outbursts from people suffering from mental illness that make it difficult to sleep. The San Francisco Fire Department has responded to incidents at Hammond’s shelter 164 times this year, fielding calls for overdoses, psychiatric emergencies and animal attacks.

Hammond’s shelter sleeps up to 200 people in lines of cots. There is a shared bathroom, pets are allowed and rules around drug use aren’t enforced, he said. Clients from other shelters also said they’ve had hardly any contact with their case manager since entering the facilities.

“I’m seriously considering just grabbing my tent and going somewhere,” Hammond said. “I would rather take my chances with the cougars and bears than these people.”

A Shift to a ‘Shelter-First’ Policy?

As pressure mounts on San Francisco leaders to tangibly improve the city’s street conditions, some officials have called for a shift in the city’s strategy to focus on filling and adding shelter beds.

The change in policy, which Mayor London Breed called a “shelter-first” approach during a press conference in May, would stand in contrast from the city’s long-standing policy to build permanent housing as the primary approach to ending homelessness.

City officials are facing increasing scrutiny from the public, but also legal pressure from a lawsuit alleging that the city has acted inhumanely by clearing homeless encampments without providing shelter beds.

As of this week, there were 2,851 people sleeping in temporary shelters in San Francisco, filling 91% of the total 3,141 beds available. Meanwhile, over 4,000 people are sleeping on the city’s streets on any given night, according to the most recent count. The waitlist for a shelter bed was 330 people long on Thursday.

In July, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing announced it would increase its target occupancy rate for the city’s existing shelters from 90% to 95%, keeping just a few beds vacant in order to accommodate emergency admissions by people being discharged from hospitals and jails.

In a statement, the department pointed to a $6.3 million investment it made last year to provide one case manager for every 25 clients in adult shelters and one case manager for every 15 clients in family shelters. The department said it’s also invested in a 10-part training series for shelter case managers to better serve their clients.

“Provider staffing challenges and case management training are key to the success of the case management program and [our department] is working with providers to ensure they have the resources they need to provide these services,” the department said.

But plans to offer more people shelter beds are fueling concerns among some current occupants who foresee an influx squeezing the already limited services. Many shelter occupants who spoke to The Standard said they wanted to live in a facility that would prepare them to live on their own, rather than just placing them on a waitlist for subsidized housing. The city offers permanent supportive housing, single-room occupancy units and housing vouchers for people based on the length of their homelessness and their vulnerability if they were to be left on the streets.

“You can help yourself here, but they’re not going to help you,” said Daniel Moore, who lives in a shelter called Next Door, a four-story building in the Tenderloin that sleeps up to 100 people in a room. “What people need is opportunity.”

Critics of the shelter system said they could use more help from staff on their resumes, setting up interviews and other steps needed to land a job in the city. A staff member at one of the city’s larger shelters, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they are not allowed to speak to the media, said they’re responsible for more than 45 clients at a time.

The city currently provides beds for 16,732 (opens in new tab) (opens in new tab)people (opens in new tab) in permanent housing, making up 56% of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s two-year, $1.35 billion budget. Meanwhile, the department has allocated 23% of its budget to maintain and staff 3,144 shelter beds.

Those who support the shift to a shelter-first policy say the city can’t continue to pursue policies that aren’t producing immediate results on the streets. They contend that permanent supportive housing costs more upfront and many people will eventually recover from homelessness and be self-sufficient, making shelter beds the more sensible investment.

‘The Only Thing I Have To Keep Me Living’

Proponents of the housing-first approach argue that shelter is more expensive to maintain than housing and doesn’t solve homelessness. They contend the city’s housing-first policy has led to a decrease in chronic homelessness in recent years. Approximately 2,691 people—or 35% of the city’s total homeless population—are chronically homeless, according to the most recent count.

Kevin Hill, who became disabled at age 20 due to an electric shock from a downed power line, said he would be unable to survive at his age without the subsidized housing that he was granted this year.

Hill, 64, said he never learned to read or write. He described bouncing around the city’s shelter systems for roughly five years before landing in a subsidized one-bedroom apartment on Polk Street. He spends $300 of his monthly social security income on rent.

“That’s the only thing I have to keep me living,” Hill said. “I went through a lot of ups and downs, but I’m OK now.”

The debate over housing versus shelter hit a boiling point in December when a federal judge issued a ruling that the city says effectively banned San Francisco from displacing homeless people from encampments without first offering everyone a shelter bed. However, the city continues to move some encampments. The ruling thrust the city’s shelter shortage into the spotlight and prompted some lawmakers to call for a change in city policy to immediately open more shelter beds.

But many contend that without an equal or greater investment in services, those shelter beds will do little to solve the crisis long-term.

“That’s not the way to deal with the problem, and they very well know that,” Hammond said.