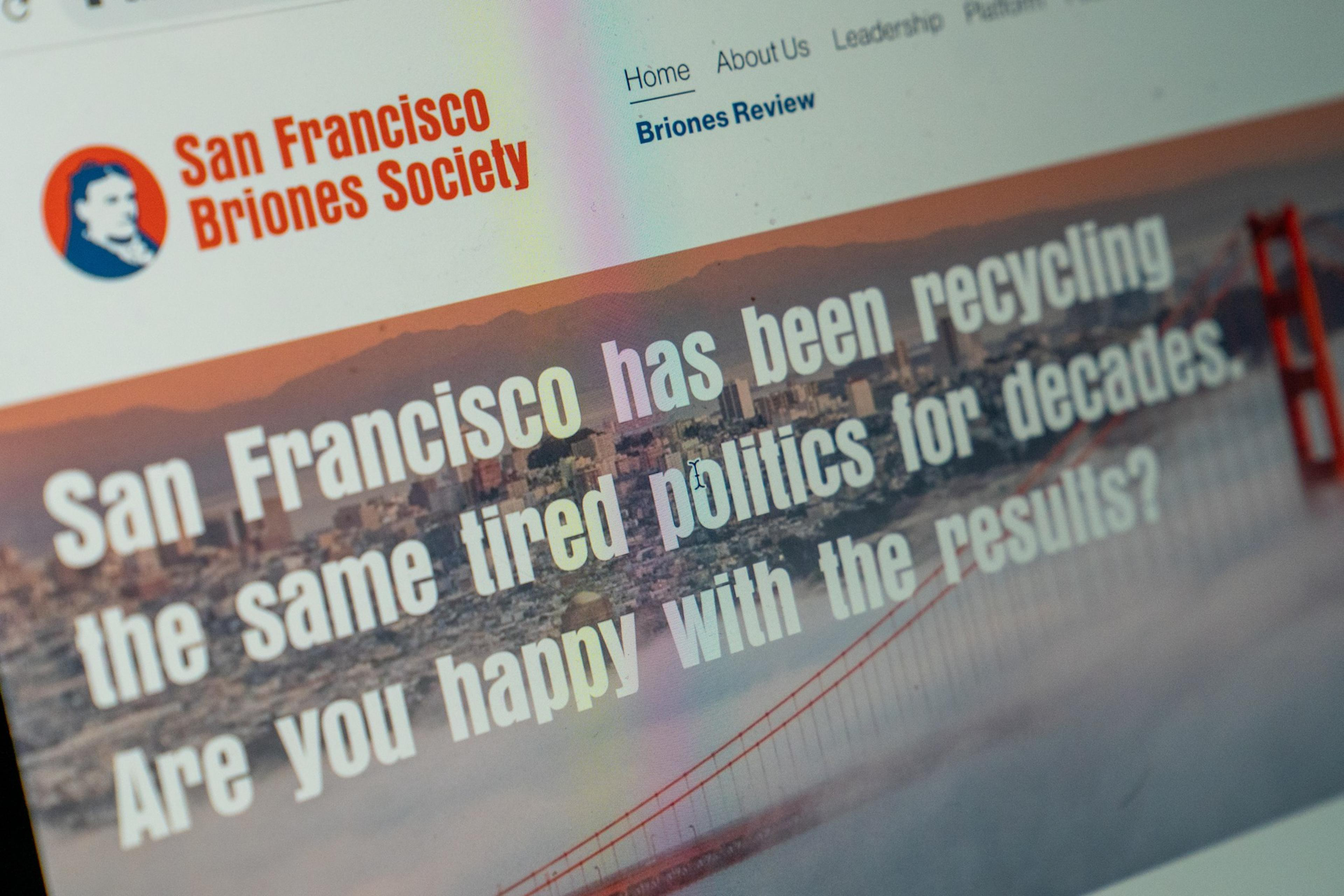

A new San Francisco political group believes it can do the seemingly impossible: Make Republicanism relevant again on the local stage.

Republicans make up just 7% of registered voters in San Francisco, with the GOP more often serving as a bogeyman than a viable political force in the heavily Democratic city. The city hasn’t had a Republican mayor since 1964, and—particularly during the Trump years—association with Republicans has been a popular canard for candidates seeking to paint their opponents as too conservative for San Francisco.

Now, a group called the Briones Society, which describes itself as “center-right,” is running a slate of candidates for the San Francisco Republican County Central Committee—the governing body for the local party—with the goal of energizing what its founders see as an underrepresented base of conservative-leaning voters in San Francisco. That may include independents and even a few Democrats, according to its co-founder, attorney Jay Donde.

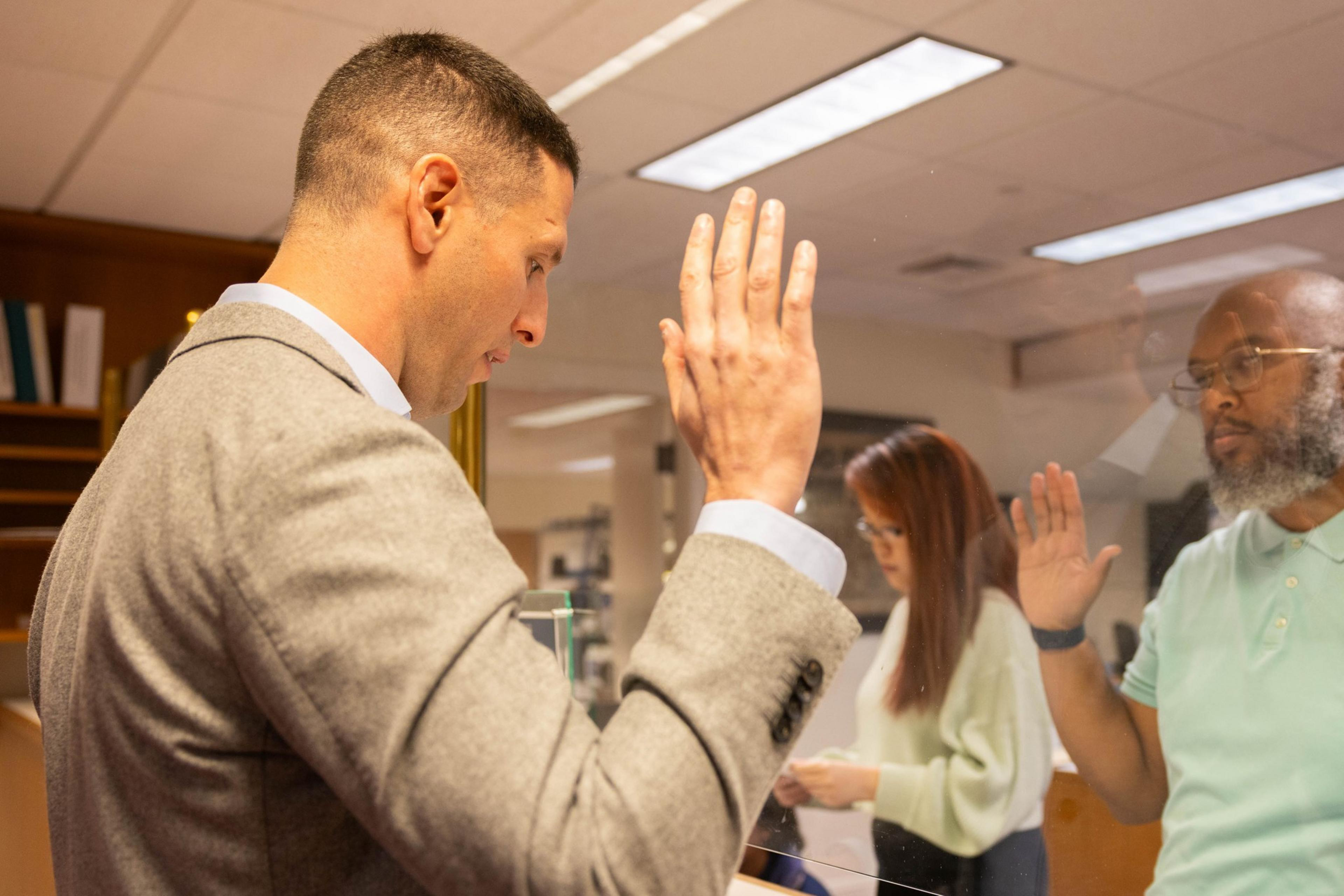

“We believe that at least a third of [registered independents] are conservative, right-leaning people that just may have become disillusioned with the party over the last 10 or 15 years and that at least 10% of registered Democrats are right-leaning,” Donde said outside the Department of Elections, where a slate of candidates gathered to file paperwork Wednesday afternoon.

In Donde’s estimation, there’s a constituency of around 100,000 conservative-leaning San Francisco voters who aren’t well-served by the current Republican party. Emphasizing optimism and competence, he believes that the Briones Society can attract an ideologically diverse range of voters who care about issues like quality schools, public safety and cutting bloat in city government—issues that even many Democrats support.

Part of Donde’s pitch is that voters “tend to trust Republicans on issues like education and public safety.”

“The Democrats are vulnerable on a number of issues,” he said. “It may be very difficult to get a Republican mayor elected in the next 3 or 4 years, [but] I certainly think it’s possible, especially given what we’ve seen across the country, to get Republicans elected to school board or to community college board or even to sheriff.”

The Trump Question

Still, convincing voters to vote Republican in a city where Donald Trump won less than 60,000 votes in 2020 is a tall order.

Republican registration has declined steadily since the 1960s. But the ugliness and rancor of the Trump years—capped off by the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the Capitol—seemed to seal the estrangement. It’s difficult to imagine much of a Republican revival locally with Trump as the party’s standard-bearer.

“It would take a sea change in the Republican Party nationally first and an economic recession that is really bad,” said Jason McDaniel, professor of political science at San Francisco State University, in a recent interview. “If Trump loses again, we’ll see some changes. But it’s still not going to be a moderate party.”

Trump’s dominance has fueled divisions within the national party, and similar divisions have occasionally bubbled up locally.

“The Briones Society introduced a resolution, to make a long story short, condemning Trump,” recalled John Dennis, who has chaired the San Francisco Republican Party since 2019 and repeatedly challenged Nancy Pelosi in Congress. “It was a very divisive thing. I warned those guys at the time it was going to have reverberations for a long time, and it was completely rejected.”

But local divisions aren’t just about Trump. In interviews with The Standard, Republicans described squabbles at committee meetings, backstabbing and infighting that they believe has gotten in the way of growing the party.

Those squabbles have occasionally spilled out into public view. In 2022, the San Francisco Republican Party adopted a resolution censuring the Briones Society (opens in new tab) for supporting Covid vaccines, describing Republican Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene as “toxic” and condemning Trump’s instigation of the Jan. 6 Capitol attack, among other offenses. In February, a video published on YouTube (opens in new tab) appeared to show a combative exchange at a committee meeting over a lawsuit filed against Dennis. (The lawsuit was tossed out.)

“Whenever a group of people shows up to a dysfunctional organization and has the courage to point out that it’s not fulfilling its responsibility to voters, … that’s going to make waves,” Donde said.

Power Struggles

Richie Greenberg, a former Republican mayoral candidate who left the party in 2020, described the dynamic as a “power struggle between the San Francisco GOP long-time, old guard delegates and the desire to rebrand.”

Dennis dismissed the accounts of infighting, contending that party disputes are normal and sometimes arising from “typical political jealousy.” He said that disruptive incidents led him to bring in a parliamentarian to help manage committee meetings. Now, the meetings are well-run, he said, and the party is “functioning exceptionally well.”

Dennis pointed out that under his tenure as chair, Republican registration in San Francisco started growing again after years of decline—albeit modestly.

Between 2019 and today, citywide Republican registration increased from about 6.4% to just above 7%. Though the raw numbers are much smaller on the Republican side, party officials note that the ratio of Democrats to Republican voters—there are roughly 9 Democrats for every Republican in the city—is narrowing. They see growth in neighborhoods such as the Outer Sunset, where registration is closer to 10%.

“We’re growing faster than the Democratic Party—we have more room for growth,” Dennis said. “But think about the energy it takes to reregister to become a Republican in San Francisco. It’s just not something to overlook.”

Dennis said he supports the Briones Society but is skeptical that it will make a big impact.

“I’m a libertarian, a pretty orthodox libertarian, and my experience is that the two major parties consist of factions and the role of the chairman is to ensure those factions succeed, that their voices are heard,” Dennis said.

“At the end of the day, they’re trying to pull a moderate coup,” he later added.

Donde, who describes himself as a longtime conservative, said that the Briones Society is a mix of “experienced activists and successful businesspeople” who represent a range of viewpoints. Some of its members cut their teeth during the successful recalls of three Board of Education members and former District Attorney Chesa Boudin—evidence, he said, that they can build an infrastructure of political clubs and volunteers to help elevate their message.

The Briones Society’s candidates include Jason Clark, an attorney and former chair of the San Francisco Republican Party; Bill Jackson, a startup founder; Martha Conte, a philanthropist and vice president of the national political organization No Labels (opens in new tab); and Jeremiah Boehner, a marketing professional and candidate for District 1 supervisor.

“The SF GOP has one club, and that’s just a recipe for groupthink and conflict on the central committee, because not everyone has to agree on everything,” Donde said. “And it limits our ability to appeal to different constituencies.”

While the Briones Society’s message of public safety, efficient government and educational opportunity may hold some appeal in a city with many frustrated voters (opens in new tab), the jury’s still out on whether it can win over enough Republicans to take charge of the local party.

On both the Democratic and Republican sides, central committee elections are often overlooked by voters and come down to name recognition; another Republican group called Citizens for a Better San Francisco is also expected to run a slate.

As for Dennis, he’s undecided on whether he’ll seek another term as party chair.

“The California Republican party has 25 members, and three come from San Francisco,” he said. “That’s what I’d like my legacy to be, that we see people move up and become contributors.”

Correction: A photo caption in this story was updated with the proper spelling of Briones Society member David Cuadro’s name.