It could be a scene from a blockbuster movie: A blind millionaire’s valet checks in on him after a devastating earthquake and discovers he slept through the whole thing—even though half of his building, including the exact spot where he would get out of bed every day—has been destroyed. Ever loyal, the valet gingerly guides his boss out of bed over the broken floorboards and retrieves $75,000 from a warped safe in the old man’s office.

But this wasn’t a movie. It’s the real life of one Aurelious P. Alberga—and it’s just one of the many Black experiences of the 1906 Great Earthquake in San Francisco, stories that have remained largely untold for well over a century.

“It’s very common, the erasure of Black folks’ existence in San Francisco at the time,” said tanea lunsford lynx, an artist and writer (opens in new tab) who discovered Alberga’s story when researching the oral history collection Afro-Americans in San Francisco Prior to World War II.

Lynx knew she wanted to work with oral histories—narrative accounts that don’t yet appear in any books—but she had no idea about the thrilling discovery she would make during her tenure as the artist in residence at the San Francisco Public Library.

“I began listening, and the stories that were born out of this man just blew my mind,” lynx said in reference to Alberga. “He was in his 90s and lived to be 103, so there are a ton of stories.” Alberga’s wife said he was the first Black man to serve as an officer (opens in new tab) in the U.S. Army, and the veteran fought for nine months in France during World War I.

Yet, it was Alberga’s experience of the 1906 earthquake that captivated her most. The historian Albert Broussard, now a professor at Texas A&M University, conducted the interview with Alberga in 1976 as part of his Ph.D. research.

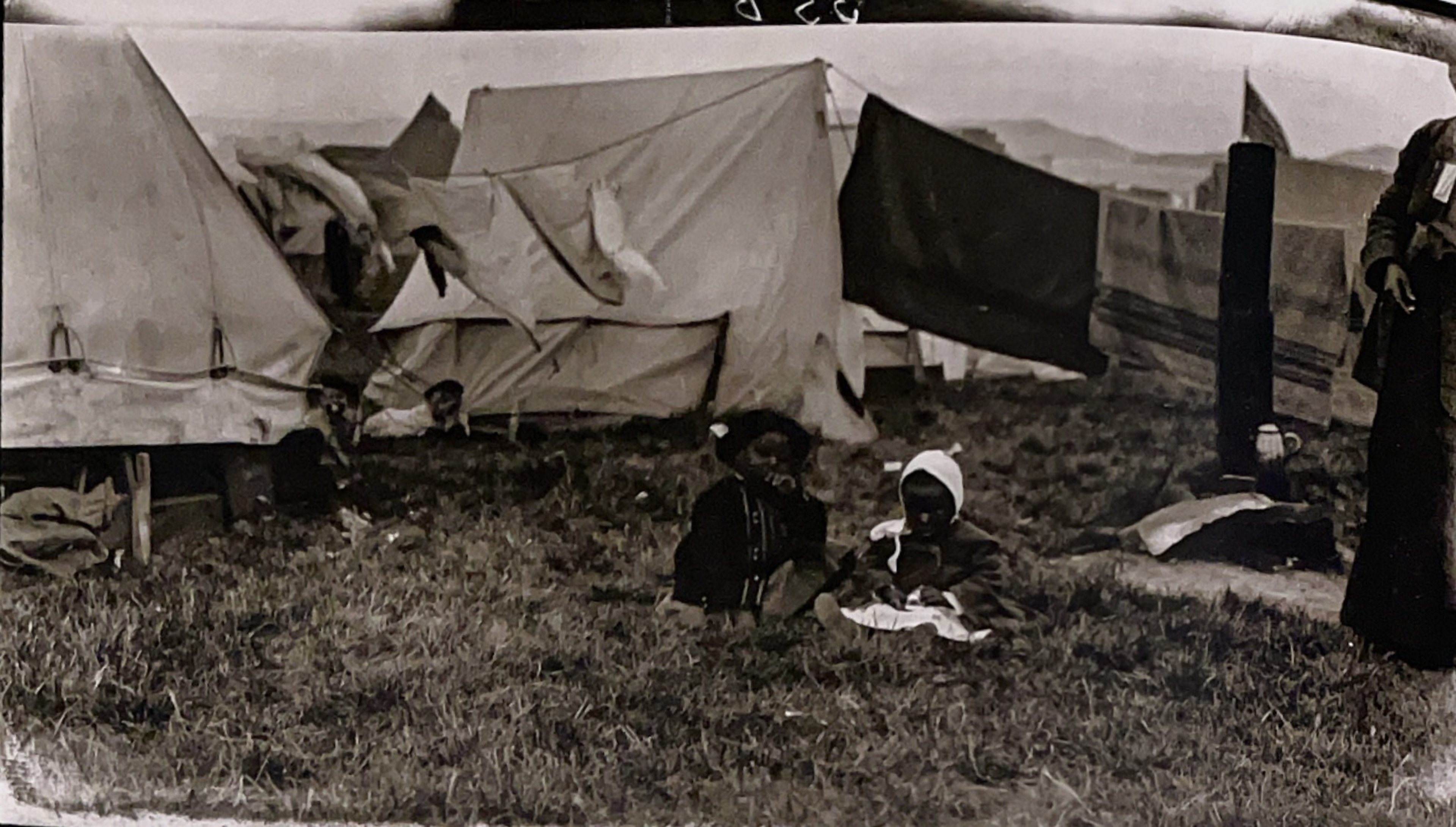

The discovery prompted lynx to further explore the Black experience of the quake, the results of which are the basis of a new exhibition (opens in new tab), “we were here,” which opens Dec. 21 at the African American Center on the Main branch’s third floor. A partnership between the San Francisco Arts Commission—which also supports the artist-in-residence program—and the library, it includes audio clips and archival photographs alongside lynx’s writing and reflections.

Lynx’s research wasn’t always easy. Many resources were destroyed during or immediately after the quake, plus there was another challenge in that the accounts of Black residents often weren’t deemed worthy of recording.

“A lot of the work was listening to the loud silences I found,” she said.

Yet there are sources—and also surprises. For example, while many ethnic groups in San Francisco saw their populations dwindle after the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco’s Black population expanded, lynx said.

“We see this pattern happening a lot when it comes to devastation: Black folks in particular, the resilience and the community of coming together to support each other after conditions have been catastrophic,” she said.

According to Alberga’s account, an outpouring of solidarity and camaraderie occurred throughout the city. He describes residents as cheerful, not sad or crying, because they were eager to help one another out. The former valet said “there was absolutely no question” that residents opened their homes to neighbors who had lost everything.

“I don’t think there were any people anywhere else in the world who were as friendly as the old San Franciscans,” he said.

In the end, Alberga’s voice is just one of many that could be added back into our understanding of San Francisco.

“There’s so much more Black history in this city,” lynx said. “We just have to find it and reclaim it.”