One of San Francisco’s largest homeless shelters for families is forced to turn away about four families every day, according to the nonprofit that runs the shelter.

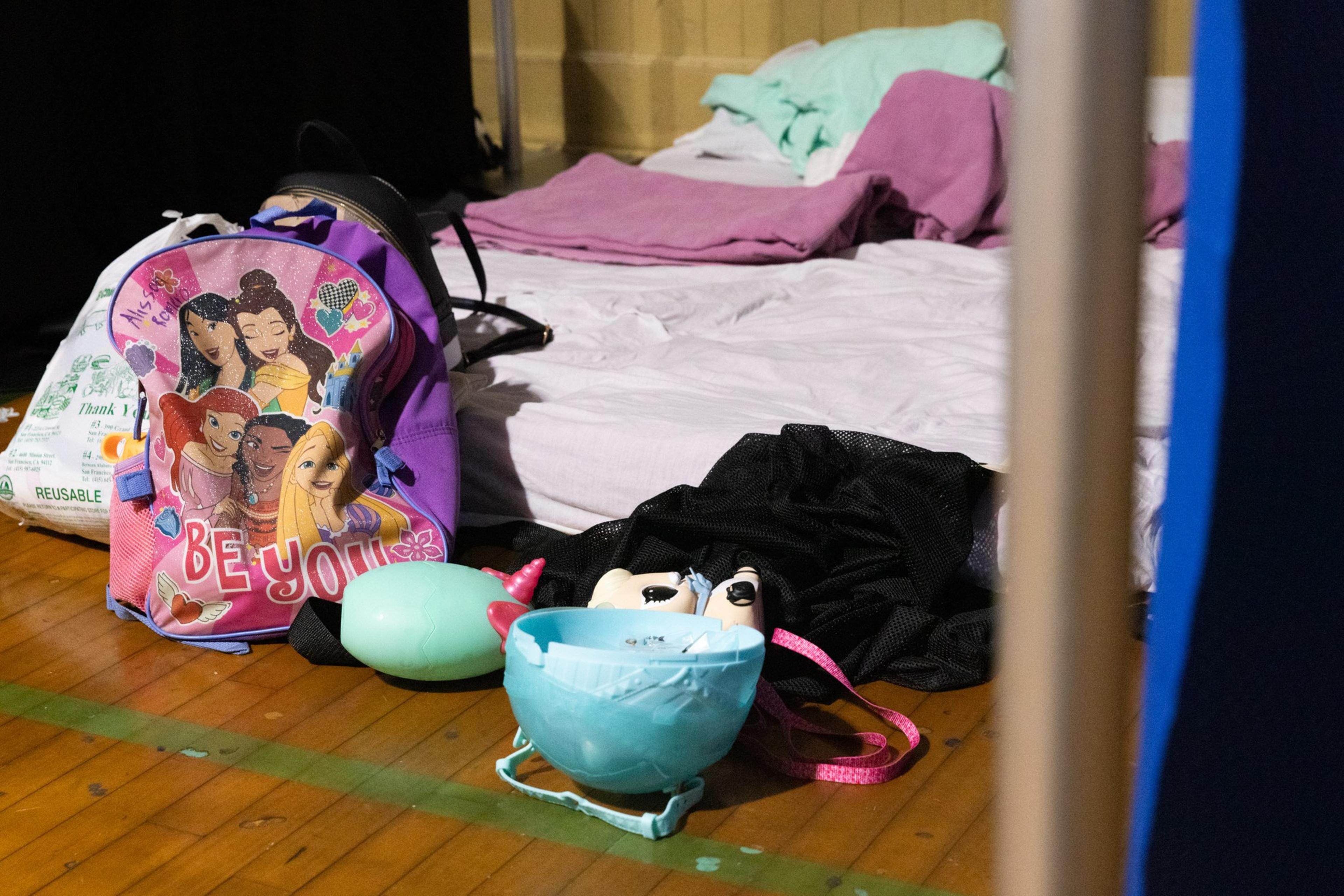

Laura Valdéz, executive director of Dolores Street Community Services, said the organization’s family shelter—which operates after hours at Buena Vista Horace Mann School on Valencia Street—is short on beds and food, causing its staff to send parents and young children back to the streets on a nightly basis.

Valdéz alleged, along with a chorus of other homelessness nonprofits, that the city overlooks impoverished families because they’re often not as visible as individuals living on the streets.

READ MORE: Are Homeless People Living on San Francisco Rooftops?

“Every night, we’re turning away families with school-age children,” Valdéz said. “They haven’t showered in days, and they’re staying in a park. … We’ve had families riding the Mission BART back and forth for shelter.”

By 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, 30 minutes after the shelter opened, Valdéz received two families she didn’t have space for.

One of the families, who asked not to be named because of their immigration status, told The Standard they unsuccessfully tried to enter a shelter in San Francisco many times over the past year.

The woman, who was joined by her husband and her two children, said the family was repeatedly evicted from different apartments because their 4-year-old son suffers from mental illness and throws tantrums. Like many migrants, they lived in communal homes without a lease, so they weren’t protected by anti-eviction laws.

Since getting evicted from their most recent apartment in the Bayview in September, the family has lived in a Ford SUV, subsisting off scraps of food and taking turns staying awake at night, they said.

“It’s cold,” the father said. “We have to use the bathroom in the park. I don’t feel safe leaving them in the car while I go out and work.”

On Tuesday, Valdéz was able to secure a 14-day hotel room for the family. She fears, however, the process will repeat itself when those two weeks are over.

Nonprofits Demand a ‘Real Count’

Representatives from the Chinatown Community Development Center, Compass Family Services, Dolores Street Community Services, Glide, Hamilton Families, Homeless Prenatal Program, SF City Vitals and the Coalition on Homelessness are coming together to demand the city conduct a “real count” of the number of homeless families in San Francisco.

In a 13-page report, the organizations argue the city places too much emphasis on counting visibly homeless people on the street, where families are unlikely to live, funneling a disproportionate share of resources toward homeless individuals while mothers, fathers and children fall below the radar.

The city’s most recent homeless biennial “point in time” count—which tallied the number of people sleeping in shelters and on the streets on a single night in February 2022—found 205 homeless families, 87% of whom were already sheltered or in transitional housing.

However, the San Francisco Unified School District estimated there were 2,370 homeless students in the city last year. Data from the State of California’s Homeless Data Integration System shows 4,990 homeless families engaged with social services in San Francisco last fiscal year.

Valdéz said her nonprofit is told not to track the number of people they turn away, effectively keeping many homeless families invisible to city leaders. She estimates the nonprofit would need $194,000 to fund 11 additional beds at the family shelter. The nonprofit is set to receive $4.7 million in total this fiscal year to operate the shelter, according to a city database.

“We’re told we shouldn’t keep a waitlist,” Valdéz said. “It’s a structural churn that the department creates to keep up a mirage that the city is providing sufficient resources.”

The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing has a budget of $713 million for this fiscal year.

Emily Cohen, deputy director for communications and legislative affairs at the homelessness department, said the department acknowledges the city’s point-in-time count likely underestimates the scope of family homelessness.

Cohen contended the city does have capacity for some homeless families, citing four empty beds at dormitory-style shelter facilities and 13 available beds at single-room shelters and transitional housing programs as of Tuesday afternoon. In total, she said the city funds 13 family shelters with a total of 620 beds and 2,323 housing units for formerly homeless families.

“We are aware that the family shelter system is more impacted than usual,” Cohen said, noting an increase in demand among homeless families in recent months. “Families in need of shelter should visit one of our access points right away.”

Valdez countered that by the time her shelter opens at 7 p.m., the access points are closed and the resources are often depleted.

‘Sinking Lower and Lower’

A mother living in a van on Lake Merced Boulevard, who asked not to be named because she’s fleeing domestic violence, told The Standard she was unable to access shelter because she lacked proper documentation.

Cohen told The Standard the city doesn’t ask questions about immigration status to enter shelters and most housing programs, though some federally funded housing requires documentation.

The mother, who immigrated to the U.S. when she was 7 years old, said she became homeless earlier this year after the father of her 5-year-old son abandoned them. She described surviving on donations from food banks and local charities.

“You might need a shelter spot that day, not in one or two or three months,” the mother said. “You just keep sinking lower and lower with no one to help.”

Valdéz said the family shelter shortage is disproportionately affecting Hispanic and Latino people–a group that saw a 55% uptick in their share of the city’s homeless population during the pandemic, according to the most recent point-in-time count.

“They’re arriving every day,” Valdéz said, explaining that her nonprofit has recently seen an uptick of migrants from Peru, Colombia and Venezuela. “We need to start implementing, in earnest, a plan that lives up to the principles of a sanctuary city.”

Valdéz said it’s common for Hispanic and Latino migrant families to live in shared living situations, where they aren’t protected by anti-eviction laws.

The mother living along Lake Merced said she’s working to acquire documentation but she’s worried she’ll be displaced before then, as the city is planning to install parking meters where she’s currently living.

“I’m just crossing my fingers,” she said, adding that she’s “hoping a shelter bed becomes available before then.”