Back in August, when the Nordstrom at the Westfield San Francisco Centre closed after 35 years, I thought of French fries and gin martinis. They were the highlight of a holiday shopping tradition I began decades ago with an old boyfriend. We’d work our way upward on Nordstrom’s spiral escalators, from cosmetics on the ground floor up through women’s shoes, ending at The Pub, the store’s authentic English-style taproom, where shoppers could collapse with their bags into the booths.

Department stores are dying; the era of dressing rooms and browsing items on the sale rack one-by-one has nearly gone the way of the girdle and the half-slip. But at their height in the mid-20th century, these retail palaces were much more than stores. Historian Jan Whitaker described them as “core institutions which reassured Americans by their very existence that life was good, that beauty mattered.”

The founding idea of the one-time crown jewels of retail may have been to promote convenience for a growing middle class, but they also had soda fountains and beauty salons; they put on concerts, art galleries and fashion shows. Some were the height of elegance, in Beaux Arts buildings with chandeliers and marble floors.

For San Franciscans and those nearby, “going Downtown” meant dressing up in their best, meaning jackets and ties for gentlemen and for ladies, hats and gloves, said Anne Evers Hitz, author of “Lost Department Stores of San Francisco (opens in new tab).”

The stores were an integral part of marking life’s milestones. “People would talk about getting fitted for their first bra at I. Magnin, or shopping for prom dresses,” said Hitz.

December was the month when families from around the Bay Area flocked to Union Square, and Market Street hosted opulent window displays, rooftop carnivals and parades.

Here is a look back at the most memorable seasonal traditions of San Francisco’s best-loved and bygone department stores.

La Ville de Paris

In the middle of the 19th century, a pair of French brothers who ran a silk stocking business in France, Emile & Félix Verdier, had an idea to cash in on the fast-expanding nouveau riche population of San Francisco, where Gold Rush hopefuls were pouring in. Word quickly spread among the city’s aspirational class when the brothers’ three-masted schooner, La Ville De Paris (City of Paris), arrived in the crowded San Francisco Bay laden with goods from fine laces to Cognac.

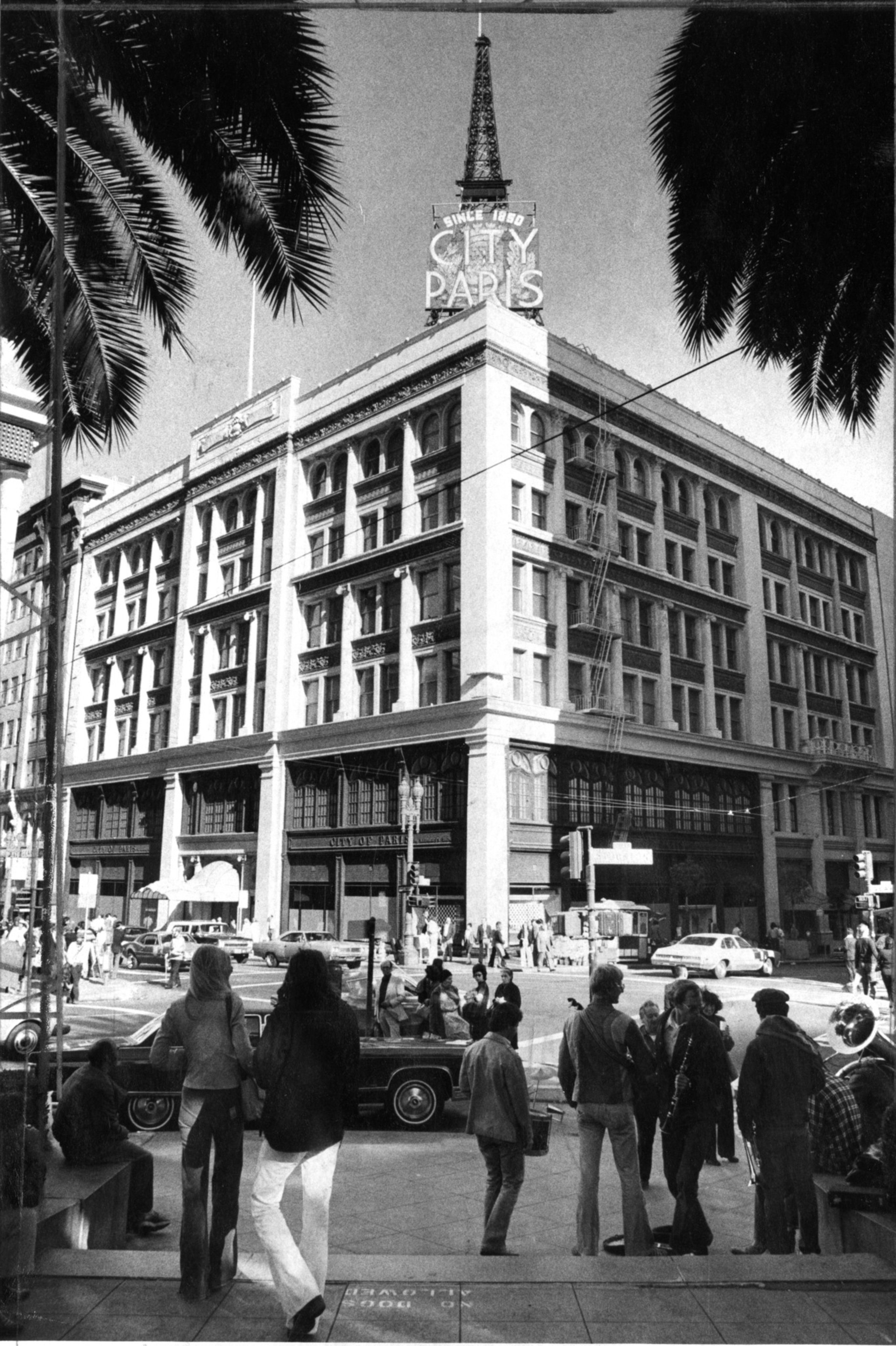

San Franciscans were so excited, Hitz writes in her book, that people rowed out in small boats to be the first to sample the fine French goods. Thus the City of Paris Dry Goods Co. became one of the first big stores to open in Union Square. It reopened after the 1906 earthquake in an ornate Beaux-Arts building at Geary and Stockton streets designed in part by architects Arthur Brown and John Bakewall (designers of the War Memorial Opera House and the Veterans Building) that had a four-story rotunda topped with a stained-glass domed skylight. A 70-foot Eiffel Tower famously stood atop the store.

That was the setting for a tradition that would endure until the store closed in the 1970s. City of Paris’s 35-foot Christmas tree—a Douglas fir crowned with a giant star that was trucked in from the northern reaches of the state—appeared “as if by magic” on the Monday morning after Thanksgiving.

“Traffic would be stopped on Geary as the tree was carried, wrapped tightly in burlap, into the store,” wrote Hitz, and a crew worked through the weekend decorating it with more than 5,000 glass balls, 800 yards of tinsel and countless packages of silver “rain” along with snowmen, candy canes and toys. The workers made a party out of decorating the tree, according to former employee Ken Strurmer, who told KQED (opens in new tab) that “by one in the morning, everybody was either drunk or stoned.”

In 1922, the store decided to skip the tree, importing performing bears and movie stars from France instead. The Chronicle reported that “San Franciscans revolted in a storm of protests by letter and phone.”

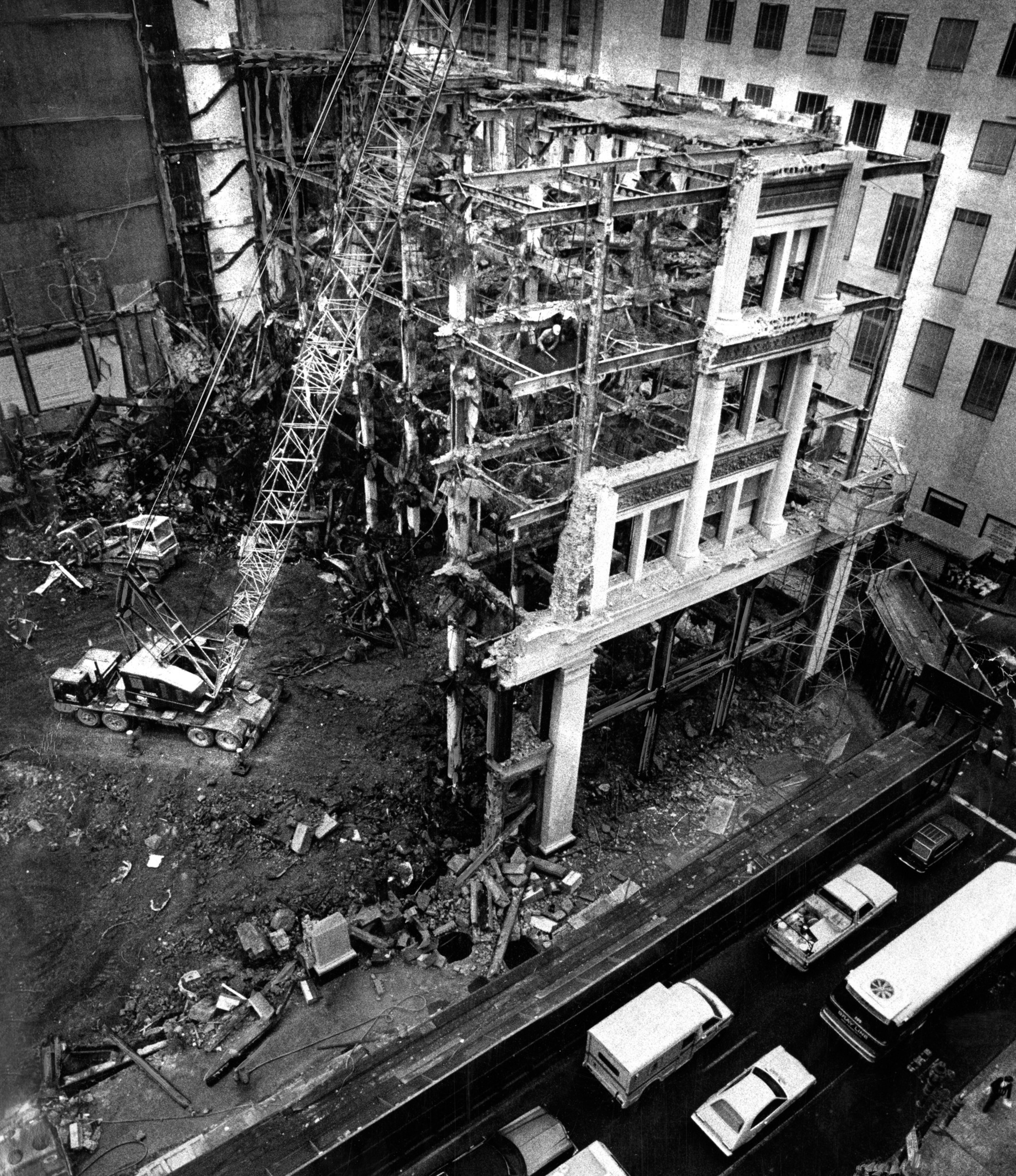

City of Paris gradually befell hard times, as women entered the workforce and global chains and discount retailers replaced the leisurely shopping experience of the grand old department stores. A years-long preservation battle followed the closure of City of Paris in 1972. Eventually, despite widespread public objection, the store was torn down in 1981 to make way for Texas-based retail chain Neiman Marcus, whose lawyer was future mayor Willie Brown.

The retailer kept the rotunda and pledged to preserve the tradition of the Christmas tree, but it “never seemed to get the tree part right,” wrote Peter Hartlaub of The Chronicle. “They started with a fake tree filled with bearded old men that frightened children, before moving on to modern Duran Duran-looking decorations later in the 1980s.”

Santa Claus is Coming to Town

If you grew up in the Bay Area before the 1990s, chances are you remember the Big E, as the Emporium was known in its last decades.

Despite the general wisdom of the late 1800s—which was that any store on the south side of Market Street was doomed to fail—German merchant F.W. Dohrmann opened the Emporium in 1896 with the idea that a store with separate departments in one building and “luxurious amenities” such as a attractive restrooms, appealing decor and extras like a tearoom and band concerts on Saturday night would appeal to the middle class, wrote Hitz, who is Dohrmann’s great-great granddaughter.

While the elegant stores of Union Square aimed at a wealthy clientele, working-class residents embraced the Emporium. The store’s ads in the early 20th century boasted that the store sold “everything that man, woman or child can eat, wear or use in their houses.”

But the store is best remembered for its Christmas festivities. Families in the Bay Area and beyond who visited San Francisco just once a year timed their annual trip into the city so their kids could visit Santa at the Downtown Emporium and take part in the rooftop carnival, which began in 1947. It even had a Ferris wheel, a carousel and a giant slide.

“It was go get your picture taken with Santa, get your caramel corn,” remembered David Phillips, a retired gymnastics coach who grew up in the South Bay and lives in North Berkeley. “From there we’d go to Gump’s and get the ornaments and then to Blum’s, which had the candy and the cake.”

The arrival of the Emporium Santa—in a horse and carriage in the early years or a cable car “Santa-Cade” in the 1940s and ’50s—was an event akin to a World Series victory parade. Tens of thousands packed the streets for the event, which from the 1930s onward featured an attraction to top the previous year, from 5,000 helium balloons one year to a parade of marchers led by a baby elephant and “assorted drummers and buglers” in 1966, according to contemporaneous accounts from the San Francisco Chronicle.

Former San Francisco Supervisor Angela Alioto told the paper in 1995: “When I was a child, I thought Santa Claus lived on the roof of the Emporium.”

The ‘Greatest Show in Town’

Many San Franciscans of a certain age remember Gump’s, the fabled San Francisco home furnishings brand, by its longtime marketing tagline: “Good taste costs no more.” Known since it opened in 1861 for its Asian and other carefully selected goods from around the world, it developed a reputation as the place to go for elegant tableware and china, and it had an entire room devoted to Baccarat crystal. The store began as a frame and mirror shop, specializing in gilding ornate wooden picture frames in gold. For much of the 20th century, Hitz notes, women of a certain social class who got engaged were assumed to be registered for gifts at Gump’s.

In 1966, the iconic Chronicle columnist Herb Caen (opens in new tab) wrote that “The city waits for Gump’s Christmas windows each season the way it waits for S.F. Ballet’s ‘Nutcracker.’”

In the 1980s, Gump’s hired six workers and spent an estimated $100,000 to arrange eight glass-enclosed chambers facing Post Street with scenes of falling snow and Japanese dolls. But the most popular display of all came in 1987, when the store featured adoptable puppies and kittens from the SPCA, a tradition that has been famously carried on by Macy’s.

Starting in the 1960s, the retail stores around Union Square began decorating their windows for the holiday season, with stores such as I. Magnin and Macy’s competing for the most elegant and creative display.

In 2018, Gump’s filed for bankruptcy. It reopened the following year under a new owner, but the proprietor has said that Gump’s future is uncertain, citing well-publicized problems such as homelessness, drug abuse and crime in and around Union Square.

Stores like Gump’s and I. Magnin—which had a fur vault and a gown salon manned by cold-eyed saleswomen with tape measures—were also known for their distinctive wrapping. The most cutting edge of these were holiday boxes made by Joseph Magnin, the specialty store at Stockton and O’Farrell streets founded by the second generation of the San Francisco department store dynasty.

JM, as people called it, became a force in the retail world in the 1960s thanks to its innovative marketing aimed at younger, working women. The Christmas boxes, designed with edgy, colorful graphics, featured non-traditional images of everything from pyramids to a gingerbread toy land village.

Some of them became collector’s items. Hitz wrote that a two-piece apparel box resembling a picnic basket titled “Christmas-dipity,” won a Gold Award in 1966 from the Folding Paper Box Association of America.

Joseph Magnin closed its doors back in 1984.

I. Magnin followed a little over a decade later, and its signature 1948 white marble building designed by San Francisco architect Timothy Pflueger now houses the French luxury goods brand Louis Vuitton.