Leanna Louie was out in the rain at the busy intersection of Taraval Street and 19th Avenue on Friday, trying to get signatures for another petition.

“Do you own a home that you want to pass on to a child?” Louie asked an elderly woman as she crossed the street. “We need your help in protecting the future generation.”

A former District 4 supervisor candidate, Louie campaigned vigorously for the recall of District Attorney Chesa Boudin and three San Francisco school board members in 2022 and advocated for the return of the merit-based admissions system at Lowell High School.

But the latest issue that has Louie and some residents of the Sunset up in arms is Proposition 19, the 2020 ballot measure that quietly overhauled the state’s decadeslong tax break for individuals inheriting property from their parents.

Quietly—because it is formally known as the “Property Tax Transfers, Exemptions, and Revenue for Wildfire Agencies and Counties Amendment,” with no mention of inheritance in the title.

Under the law, which passed with a narrow 51% yes vote, the state rolled back certain transfer tax protections. As a result, any child who inherits their parents’ property today could be subject to a higher property tax bill since the home would be reassessed at market value at the time of transfer.

If the property was the parents’ primary residence before they died, the law does carve out a special allowance (opens in new tab) to be excluded from the reassessment for the child who makes the inherited home their primary residence within one year of the transfer.

However, if the property’s fair market value still exceeds that excluded amount, then the child would be on the hook for the difference plus whatever base-year tax value they inherited. Depending on the value of the home, that could result in a tax bill increase that could amount to thousands or tens of thousands of dollars per year.

“We’re finding that Prop. 19 created unintended consequences for multigenerational households,” said Gina Tse-Louie (no relation to Leanna Louie), who has run a financial planning and real estate business in the neighborhood since 1987.

“Children who moved back into their childhood homes to care for their ailing parents or inherited homes well into retirement age are getting kicked out because they can’t afford the new tax bill,” Tse-Louie said.

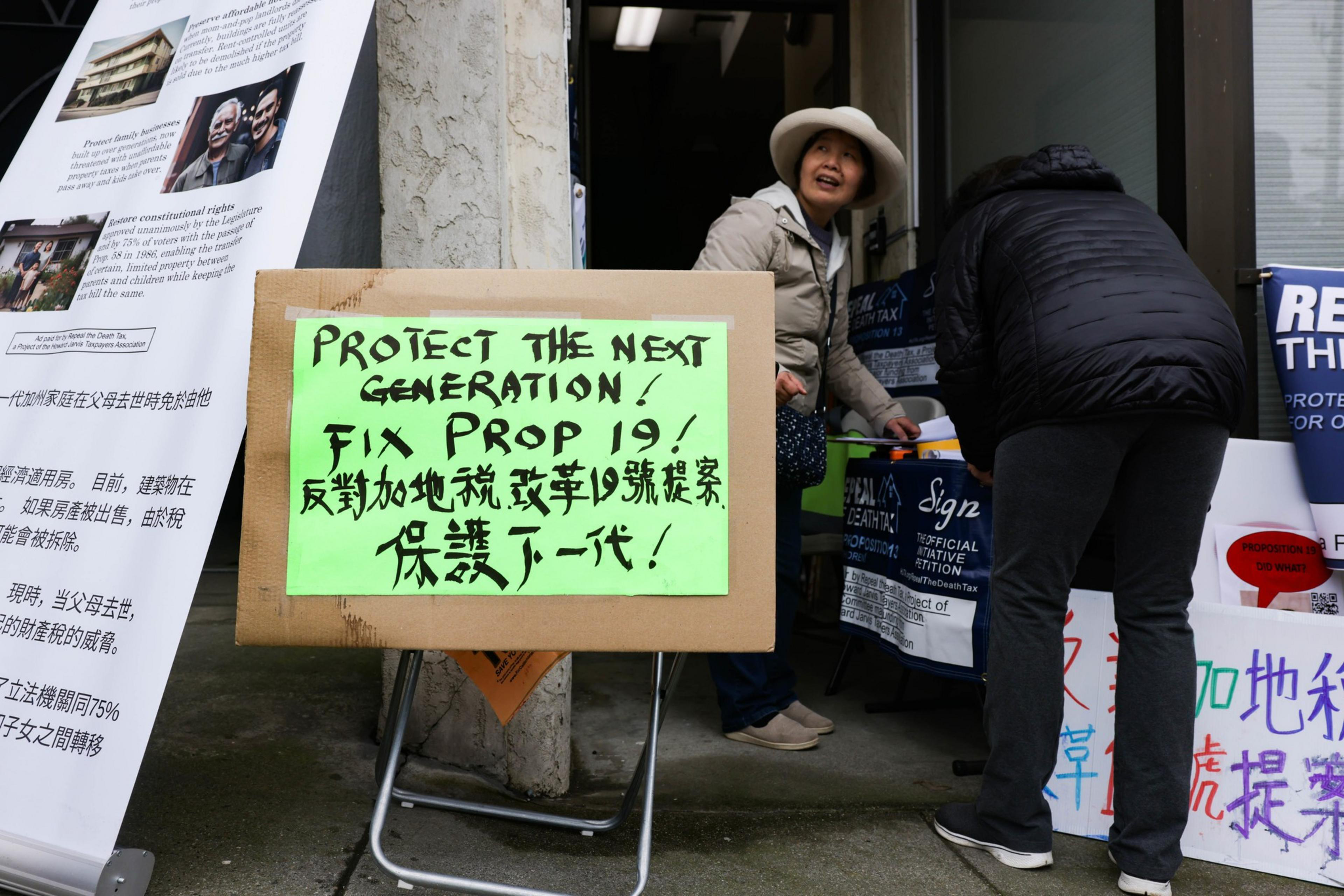

Outside of her office on Taraval Street, a small number of volunteers gathered to wave “Repeal the Death Tax” signs in English and Chinese and plead with those passing by to consider signing a petition to get the issue back on the ballot.

So far, the effort hasn’t generated the same momentum as the previous years’ recall campaigns have, but more would-be and current homeowners are becoming aware of the issue now that the tax is affecting them, Tse-Louie said.

“This is pure gentrification passed under the name of equity,” Tse-Louie said. “Only people who have the money to buy a new home right now, or big corporations and developers, can afford it.”

Since voters approved Proposition 13 in 1978, California has been the only state in the country to suppress annual property tax increases for homeowners. In subsequent years, the popular initiative (opens in new tab) was amended to allow parents to transfer those tax benefits to a child without the property’s value being reassessed.

Critics of the policy say this exemption has exacerbated the wealth gap in the state and contributed to public funding deficits because homes in expensive areas like the Bay Area and Los Angeles are being taxed based on valuations from the 1970s, rather than the millions of dollars they are worth now.

For example, a 2018 Los Angeles Times (opens in new tab) investigation found a six-bedroom home in San Francisco’s exclusive Presidio Heights neighborhood that was worth nearly $10 million was being taxed based on a 1970s sale price of just $300,000. The owners, who inherited the property, listed it for rent at $17,500 a month that year.

Before he became San Francisco’s city attorney, David Chiu, then a member of the state Assembly representing San Francisco’s eastern core, said he was in favor of eliminating the inheritance tax break because he saw it as symbolic of the state’s growing inequality gap.

“The idea of the American Dream of everyday people being able to make it is completely impacted when the haves get more, and the have-nots have no chance of benefiting from property investment windfalls,” he told the Times in 2018.

When the amendment reached the state legislature in 2019, Chiu initially voted in favor of it in committee, but after it went through revisions, he abstained when it came before the full Assembly (opens in new tab).

“I did not vote to place Proposition 19 on the ballot and did not support the measure when it was in front of voters,” Chiu said in a statement. Chiu noted he was speaking in his capacity as a former member of the state legislature and not as the city attorney.

Tse-Louie’s loose “Repeal the Death Tax” coalition acknowledges that while the inheritance tax break could be exploited by those who eventually end up renting out their inherited property, Prop. 19 hurts individuals who cared for their relatives and want to stay in the area.

She spoke of a client in West Portal, an artist who moved back in with her ailing parents years ago. The home is being foreclosed upon because she cannot afford the newly reassessed tax bill.

Elsewhere, Stephen Field told the Los Altos Town Crier of a similar experience (opens in new tab). The Los Altos native returned to his childhood home to care for his ill mother and her husband in 2020. Both of them died in 2021, and Field inherited the property, but he said he can’t afford the tax payments.

Repealing Prop. 19 in this November’s election is a long shot at this stage. In order to qualify for the ballot (opens in new tab), repeal proponents have to gather 872,000 signatures at least 131 days before the election.

Moreover, once they have gathered 25% of that amount, the state Senate and Assembly would have to hold joint public hearings on the proposed initiative before it could be put in front of voters. Tse-Louie admitted on Friday that the coalition is still well off of that mark, but she was optimistic, given how robustly Californians have supported Prop. 13.

“Prop. 19 was hastily put together during a (Covid) election and marketed inappropriately,” Tse-Louie said. “We’re just asking for a fair shot to fight this.”

While the 2020 ballot measure reined in the inheritance tax breaks, it expanded another (opens in new tab). The law allows homeowners who are severely disabled or age 55 or older, or whose homes were destroyed in a disaster or wildfire, to transfer the assessed value of their primary residence to their new residence, regardless of location in the state. That can help older Californians downsize or relocate to a home more appropriate for them without incurring a huge tax bill.

According to a 2023 Charles Schwab survey (opens in new tab) of more than 700 American investors between the ages of 27 and 95, more than three-quarters of parents plan to leave a home to their children when they die. The survey also found that nearly 70% of those who expect to inherit a home from their parents plan to sell it.

Alexandra Ayoub, an Oakland estate planning attorney, recalled taking dozens of frantic calls when voters passed Prop. 19.

“People were in a mad dash, thinking they had to transfer all of their property to their kids right away to preserve the reassessment exclusion,” Ayoub said. But out of 60 or so cases that year, her office only ended up effectuating five or six property transfers after a deeper dive into each family’s situation.

That’s because calling Prop. 19 a “new tax” isn’t entirely accurate, Ayoub said. Rather, she sees it as more of a reallocation of tax burdens that already exist. Her firm, Ayoub & Dodson LLP, primarily works with Bay Area families with an average net wealth of between $5 million and $20 million

“When you take a closer look, (Prop.19) might change how you stage your inheritance plans, but California still has a relatively advantageous property tax regime as compared with other states,” Ayoub said.

Families that own multiple properties, for example, would potentially be subject to reassessments regardless of the measure, Ayoub said. Moreover, if/when children decide to sell their inherited property, they mostly avoid having to pay capital gains tax due to what’s known as the step-up in basis upon death provision—which adjusts the cost of the property to market value, eliminating the gain that occurred between the original purchase and the heir acquiring it.

California also does not levy an estate or gift tax. Then, there are the aforementioned assessment exclusions for those children who intend to make their parents’ primary residence their own moving forward, in addition to carve-outs.

“There are for sure some families, where a house might be their only asset, that are harmed by Prop.19,” Ayoub said. “But that’s the case for propositions in general. They’re usually sloppily put together, hard to understand and circumvent the legislative process.”

For that reason, Ayoub said she wouldn’t be surprised if the measure does eventually get repealed, citing Proposition 8, which was intended to ban same-sex marriage in 2008 as an example. The measure was passed by voters before it was later overturned in court a year later.

“Prop. 19 can certainly impact you,” Ayoub said. “But it deserves a professional opinion considering your specific circumstances and objectives before you get bent out of shape.”

Editor’s note: The location of the protest in this story has been corrected, and the story has been updated to include David Chiu’s voting record on the measure that became Prop. 19.