Traffic court Judge Mario Choi was preparing to deliver his decision in the final case on his docket to an audience of 27 empty plastic white chairs. With nobody there to step forward, he began to deny the citation appeal.

But before he could finish, a man wearing green sweatpants and Crocs over socks burst into the courtroom, stammering apologies for being late, saying he’d taken the wrong bus.

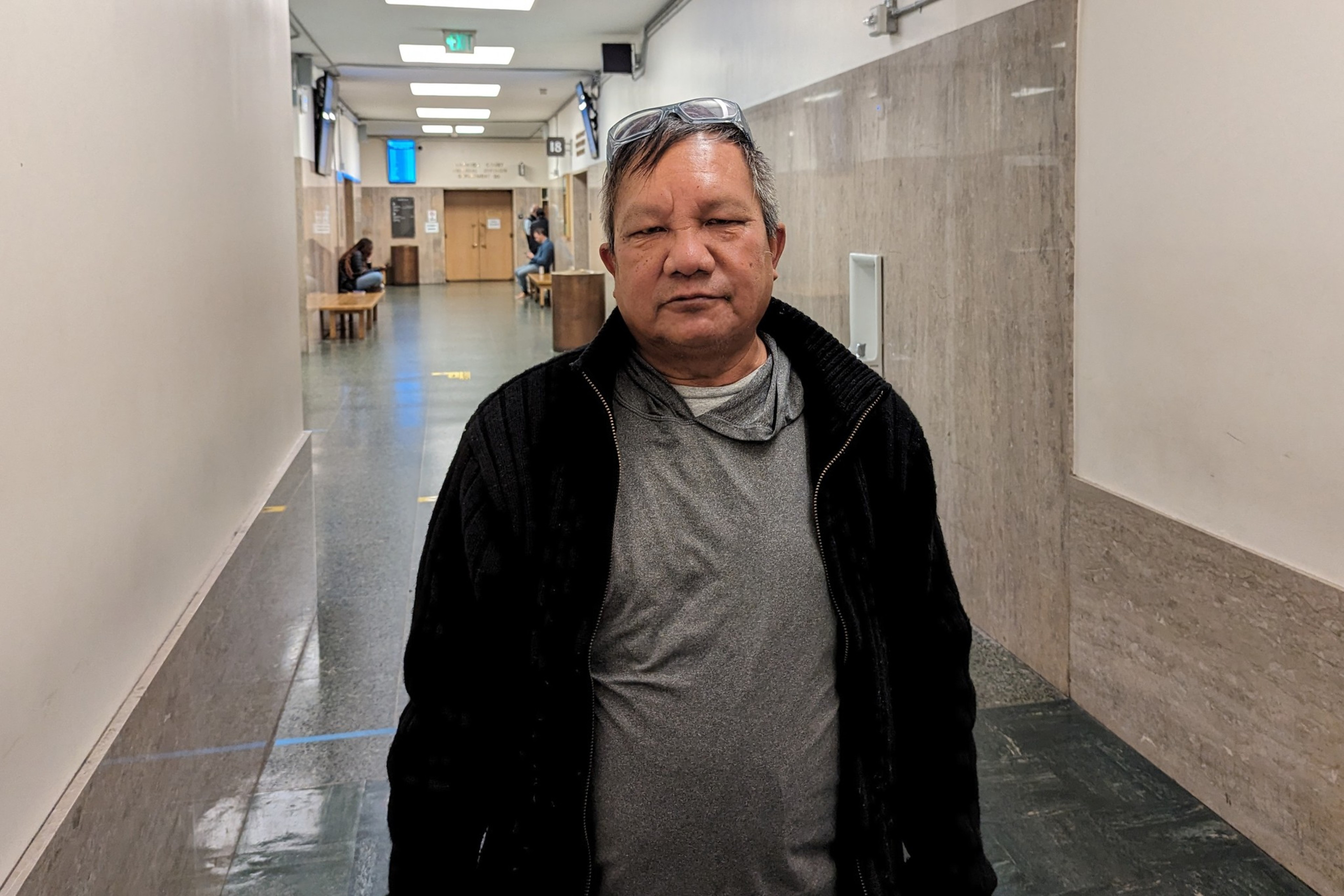

Soon, 66-year-old Won Suai had his hand in the air as he swore to tell the truth, and nothing but the truth. And traffic court was back underway.

San Francisco issues over 1 million parking citations worth north of $100 million each year. Parking control officers cruise around in single-seat vehicles daily, and residents know all too well that letting the meter expire, blocking a curb cut or parking in a red zone often ends in the dreaded ticket tucked under the wipers. In fact, locals are so diligent about curbing their wheels on hills that thieves reportedly use it as a method to identify out-of-towners (opens in new tab).

While many people simply pay their tickets and move on, more than 100,000 go unpaid each year. Some people simply elect to ignore the ticket, racking up costly fees and leaving the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency owed over $200 million, as of September 2023.

But a select group of ticket recipients choose to stand up and fight the transit agency. The stakes can be high. Academic research has found (opens in new tab) that a routine fine like a parking ticket can have a domino effect, forcing some people living paycheck to paycheck to default on other important bills.

Some contest the citations in writing, but only the most hardcore challengers take their parking ticket all the way to court. To get there, they first have to strike out on SFMTA appeals—twice. Of the over 1 million parking citations in 2023, only 307 of them made it in front of a traffic court judge, according to a court spokesperson.

The Standard spent three mornings in San Francisco’s traffic court to better understand this unique corner of the city’s justice system, where everyday people argue their cases straight to a judge. Some, it seemed, just wanted to dodge the costly fine. Others, however, sought justice for being wronged, as they saw it, by parking enforcement.

Suai, with a pair of $209 tickets for having expired registrations in hand, probably fell into both camps. He told the judge that he had placed the cars that were ticketed in planned nonoperational status with the DMV and stowed them in his driveway. The ticket agent actually walked up onto his driveway to issue the tickets, then wrote the wrong address on the citations, he said.

A folder of printed photos, featuring an image of the ticket on his windshield with his house number in the background, was enough to sway the judge to rule in his favor.

“Congratulations,” the court clerk said to Suai before he left the courtroom.

In front of the judge

The San Francisco Hall of Justice, the behemoth building on Bryant Street, is the focal point for the dispensation of justice in San Francisco.

To go inside, visitors must pass through metal detectors, under the watchful eye of sheriff’s deputies. Traffic court is just down the hall from the rooms where serious matters like murder, rape and assault are tried, but it feels like a different world. No one here is in an orange jail jumpsuit, and there are no teams of lawyers. Instead, everyday people wearing sweatshirts and sneakers step up, one by one, to a wooden podium to assert their innocence—or plead for mercy—as a judge listens.

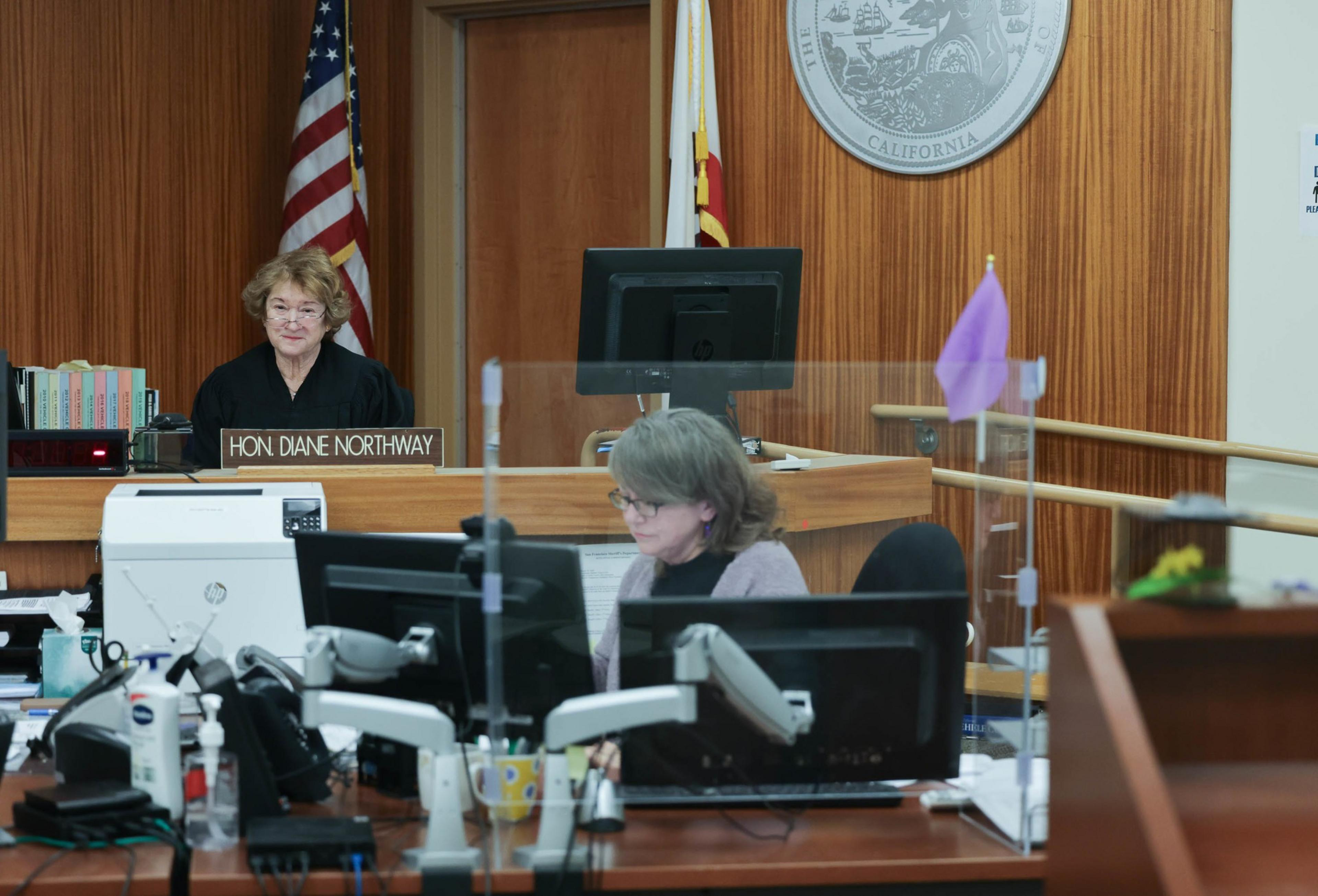

“It’s a good feeling,” Judge Diane Northway said about the direct judge-to-motorist dialogue unique to traffic court.

“It’s important for the judicial process for people without attorneys to feel listened to,” Northway said.

Of course, everyday people don’t have the courtroom savvy of a lawyer.

On Wednesday, Northway called the case of Joseph Hurley. Two men stood at the same time, with the younger quickly saying, “We’re both Joe Hurley.” The father owned the car, but it was the son who parked it, the pair explained.

Northway looked down at the photos she received from SFMTA for evidence of the allegedly illegally parked vehicle in the Hurley case. She quickly said that she wanted to rule in the Hurleys’ favor, because the photos were blurry. But before she could make the ruling official, the elder Hurley spoke up, explaining that he had brought his own, better pictures.

Off to the side, the bailiff did a double take.

“Don’t show them,” he said under his breath, out of earshot of the Hurleys. It’s apparently possible to talk yourself out of a favorable ruling in traffic court.

Nonetheless, the elder Hurley passed his photos over to the clerk to be entered into evidence. Luckily for the Hurleys, the images seemed to bolster their case, because Northway quickly concluded that the parking sign in question had been defaced, making it unclear. The pair would get a refund on their deposit—equal to the amount of the ticket fine—required to take a case to traffic court, she said. The original ticket fine was $108, according to SFMTA records.

How to fight a San Francisco parking ticket

Once you receive a parking ticket in San Francisco, you have three weeks to dispute it (opens in new tab). The first step is to request an SFMTA administrative review; cited motorists can submit any photos, receipts or other evidence they have to bolster their claim online or through the mail. An average of about 70,000 people have taken this step each year since 2020, according to SFMTA data.

Legally, the citation is assumed to be valid on its face, so it’s up to the motorist to provide evidence that the violation didn’t occur or that the citation was recorded inaccurately, according to SFMTA Senior Manager Diana Hammons, who oversees the agency’s citation section.

Some of the most effective evidence people provide is photos showing that parking signs were missing or vandalized, or that curb paint had faded, Hammons said. In those cases, SFMTA will send a surveyor out to examine the location. Another persuasive piece of evidence is proof that a parking meter was broken or a receipt showing that the driver actually did feed the meter.

About a third of those first-level appeals succeed in getting the citation dismissed, according to SFMTA data.

Arguments free of hard evidence, however, rarely prevail, Hammons said. Vehicle owners who explain that they overslept for street cleaning, for example, do not get let off.

Among those who fail the first round, the option remains to request an SFMTA hearing. During the hearing, a vehicle owner has the chance to have a back-and-forth with an SFMTA officer to better explain any extenuating circumstances. An average of about 6,000 people took that step in recent years, with roughly 40% of those getting rid of their tickets.

Those who still haven’t had their ticket overturned finally have the opportunity to have their day in traffic court. There, both sides have the opportunity to present their evidence in front of a judge, though the burden is on the person appealing their ticket to provide proof of their position, according to San Francisco Superior Court spokesperson Ann Donlan. Parking control officers don’t have to come to court, Hammons said.

There are three possible outcomes to most traffic court cases, according to Donlan. The judge may find that the person committed the violation, leaving them on the hook for the full payment. On the other end, the court may dismiss the citation altogether if it finds that the person didn’t commit the violation or that the larger circumstances make the dismissal appropriate in the “interest of justice.” Somewhere in the middle, the judge may conclude that the person did commit the violation but decide to suspend the parking penalty anyway due to mitigating circumstances.

The court does not maintain data on the results of the parking citation appeals, Donlan said. On the three mornings The Standard observed traffic court, every person walked away with a victory in some form, whether that was a complete dismissal or, more commonly, a penalty suspension for mitigating circumstances.

But people shouldn’t take that to mean that all it takes to get a ticket thrown out is showing up to court, according to Northway, the judge.

“Each case is individual,” she said.

Emotional hearings

Not everyone is satisfied with simply winning their traffic-court case.

Northway decided to dismiss Rajahn Meredith’s ticket because the relevant parking sign was illegible in the photo SFMTA gave the court. The judge was poised to fill out Meredith’s paperwork when the cited motorist called out that he wanted to say something.

“Wouldn’t you like me to finish signing?” Northway said with a smile.

Meredith did, of course. But even after the ticket had been officially dismissed, he still wanted the judge to hear his side. The parking officer claimed on the citation that Meredith pulled off before they could give him the ticket, and that’s why Meredith received a ticket in the mail out of the blue.

But Meredith said the parking officer must be lying, because he’d never leave if he saw that he was in the middle of getting a ticket.

“I’m not going to be a kid and pull off,” Meredith said. He has received multiple citations making the claim that he ran away, he said.

“This is ridiculous,” Meredith said.

Outside the courtroom, Meredith extended his criticism to the entire appeal process, saying that SFMTA employees can’t be expected to make fair rulings on tickets issued by their colleagues.

“They’re employees of the MTA, so they’re already biased, so that’s just a waste of time,” Meredith said of the first two steps in the appeal process.

But other traffic court defendants left grateful to escape a steep fine, regardless of the path it took to get there.

Dilfuza Kuldasheva, for example, came to dispute a ticket for parking in a bus zone. She explained that she was driving to a downtown medical appointment with her sick 3-year-old son when she pulled over quickly to wait for a car to leave a parking spot she wanted.

“I was really shocked when I received the ticket,” Kuldasheva told the judge.

But Northway said she had a photo in hand from the SFMTA showing Kuldasheva blocking the bus stop. It’s not important why you were there, Northway told Kuldasheva.

The judge concluded that Kuldasheva committed the violation. She delivered stern warnings that the context didn’t matter. But in the end, she decided to suspend the penalty due to extenuating circumstances. SFMTA would refund the money Kuldasheva already paid, the clerk explained. The original ticket was for $380, according to SFMTA records.

In the hallway afterward, Kuldasheva radiated relief, explaining that she is a single mother with three children. Tears welled up in her eyes.

“I’m so happy,” she said.