Most books are crafted from the outside in—it all starts with the cover. But at San Francisco’s Arion Press, it’s the opposite: Books are made from the inside out, with decisions about paper type and custom font preceding ones about cover design.

It’s just one of the many ways in which the press, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, operates differently. Unlike traditional publishers, which farm out printing and binding to industrial plants and use digital fonts instead of physical ones, everything at the 14,000-square-foot bookmaking facility, nestled among green trees in the old Army barracks of the Presidio, is handcrafted under the same roof.

“We are the last vertically integrated bookmaker in the country,” said Arion Press director Rolph Blythe. He has been at the press for four years, since its founder, Andrew Hoyem, retired after over four decades at the helm.

Arion dwells in an almost extinct corner of the book world: Call it Slow Publishing. It produces only three books a year, each a unique art object reproduced in editions of less than 300. Art is so important, in fact, that the illustrators—art-world luminaries—drive the title selection process.

“We learned that the projects went a lot more smoothly when we said to the artist, ‘What do you want to do?’” Blythe said.

The latest work coming off the 17,000-pound press: Octavia Butler’s 1979 classic Kindred, a 344-page novel by the science fiction master with original artwork by the printmaker and sculptor Alison Saar, whose work focuses on the African diaspora. The few available single copies of the book are priced at $1,300; Arion’s yearlong, three-book subscription runs $2,400.

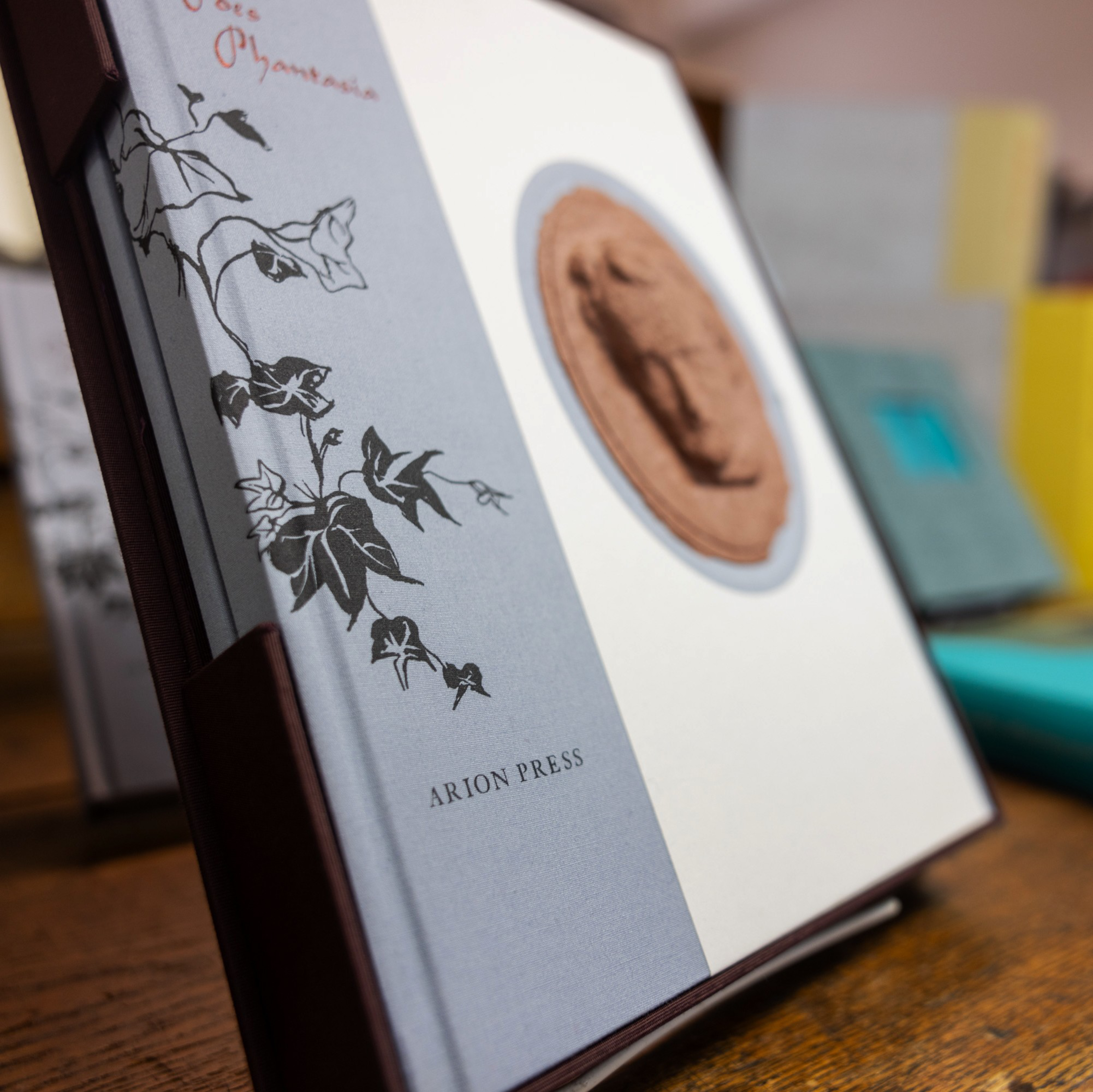

“It’s magic more than science,” said spokesperson Florie Hutchinson of the three titles per year that receive the Arion treatment. Past reprinted works include Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, John Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez, and a collection of Edgar Allan Poe’s writings, dubbed Poe’s Phantasia.

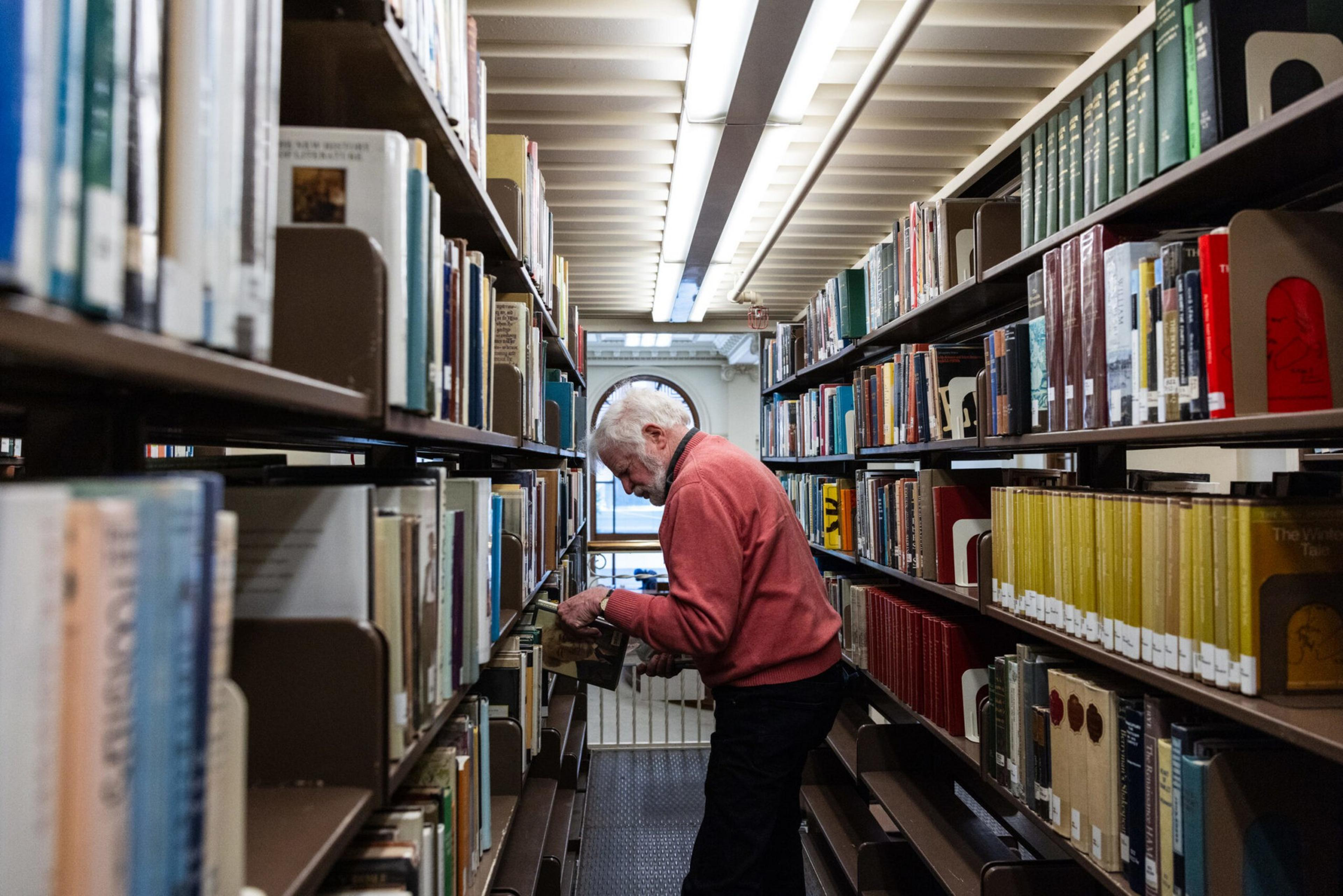

On a recent visit to the press, The Standard witnessed the practically fanatical level of detail that Arion’s printers, typecasters and bookbinders bring to their craft—especially when producing the 40-copy deluxe editions, subscriptions to which cost $10,000.

The 2023 Poe collection includes bricks from his home crushed into a fine powder and then molded into his likeness on the front cover; the 2020 Sea of Cortez includes wooden details harvested from a ship Steinbeck once sailed. “Everybody got a little bit of boat,” Blythe said. “That was really important to us.”

“There’s such a passion and drive, and there are so few people who know this skill,” said Tina Ahn, an archivist at the Mechanics’ Institute, a private library in the Financial District that has many Arion titles in its collection. “Not everyone can afford them, but you can come to places and enjoy them.”

A press like no other

Arion Press is named after the mythical Greek poet Arion, who was saved by a dolphin while drowning at sea. For Hoyem, the press’s founder, it was the perfect analogy—“like rescuing and reestablishing the practice of fine bookbinding,” said Blythe.

Arion got its start in 1974, but its roots stretch all the way back to 1919, with the establishment of Grabhorn Press in San Francisco, known for its museum-quality printed books, like a 1930 edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. When Grabhorn closed in 1965, Hoyem partnered with co-founder Robert Grabhorn to preserve the press’s vast collection of equipment and typefaces.

Nearly 50 years later, the press maintains its commitment to the art of the fine press.

“Apple ruined the word ‘font,’” said Brian Ferrett, foundry manager, as he gestured to stacks of paper-covered bricks lining a long wall on the press’s lower level. The press sells its large collection of fonts to hobbyists and other small presses—capital letters weigh nearly twice as much as lowercase ones.

For its own books, Arion Press handcasts type from its drawers of metal molds, where the letters are sorted not alphabetically but organizationally: “a” is next to “r” and “i” is next to “s” because they are so often close together. “E”—the most common letter in the English alphabet—boasts the biggest section.

After working at Arion Press for 16 years, and in offset and letterpress printing before that, Ferrett can pull letters out of the hundreds of drawers by memory. He slots the metal pieces backward into a mat case and takes the molds to the foundry room, where a mixture of lead, tin and antimony is heated to 680 degrees Fahrenheit.

“This is one of the few places to learn the art of casting,” he said.

The molten metal fills the letter-shaped chambers, creating one-of-a-kind type. There are other foundries like this across the country, but it’s unusual to find one operating right alongside the printing press and the book-binding operations.

“Here, it’s all three together working every day,” Ferrett said.

Once a project is finished, the painstakingly assembled metal type is not saved for posterity. Instead, it’s essentially recycled—thrown into worn wooden crates called “hell boxes” to be melted down in the foundry and recast again.

“It’s an entirely circular process,” Ferrett said. Each book Arion creates is “impossible to produce again.”

No delete key

Once a book’s type has been set, it gets broken into lines and then set into pages in the composing room. A metal cabinet holds each individual sheet of type in a tray, its page number marked in chalk.

A sheet-fed, two-color Miller press—manufactured in Pittsburgh and one of the last of its kind still in production—prints the books’ pages, which themselves have been carefully selected to have just the right weight and feel for the project. (Kindred includes a specialty red Japanese paper called Moriki Kozo.)

The sheet passes through the printing press as the cylinder drops down—and that’s when the magic happens, said Blake Riley, Arion Press’ creative director. “We want to keep that impression right where we want it,” he said. According to Riley, the ink varies from day to day and is subject to temperature changes.

The creative director is a relentless perfectionist, hovering over the press with tweezers in his Carhartt apron to adjust type that is coming out too dark.

“There’s no delete key in our process,” Riley said.

Saar, the artist behind the 12 original linoleum cuts included in Kindred, created illustrations that don’t shy away from the harsh reality of the book’s subject matter: the feet of Alice after she’s hung herself in the barn and the knife Dana uses to slit her wrists are depicted in searing black-and-white detail.

“There’s no escaping the inherent violence embedded in this story of human enslavement,” Riley said.

Bound for life

The last step for an Arion Press book is binding, which requires a lengthy prototyping process. During The Standard’s visit, lead bookbinder Megan Gibes and her team were cutting cardboard mats and examining materials to cover them. On one table lay a spread of animal hides from the Pergamena Tannery in the Hudson Valley.

“They’re known for making the most fine leathers,” said bookbinder John DeMerritt, who works part-time at the press. “But we asked for leather that was not so fine.”

The bookbinding team was trying to find just the right skin to cover the deluxe edition of Kindred, and just the right color thread for sewing the book together. Decisions regarding the cover are the last to be made.

Bridging science fiction and fantasy and both a feminist and Afrofuturist touchstone, Kindred is a particularly complex and rich work. It feels fitting to be the last edition Arion will produce in its home of over 20 years in the Presidio, a title worthy of the utmost care and attention, the 128th work the press has produced.

Later in the year, Arion Press will move—a victim, like so many other small businesses, of rising rents—downsizing to a 10,000-square-foot facility in Fort Mason. But the new space will be much more visible to the public, occupying the entire ground floor of Building B, with the opportunity for passersby to peer into the windows and see a craft unlike any other in action.

“We’re able to have this constant dialogue with each other,” DeMerritt said, “all under one roof.”