San Francisco’s Hall of Justice is falling apart.

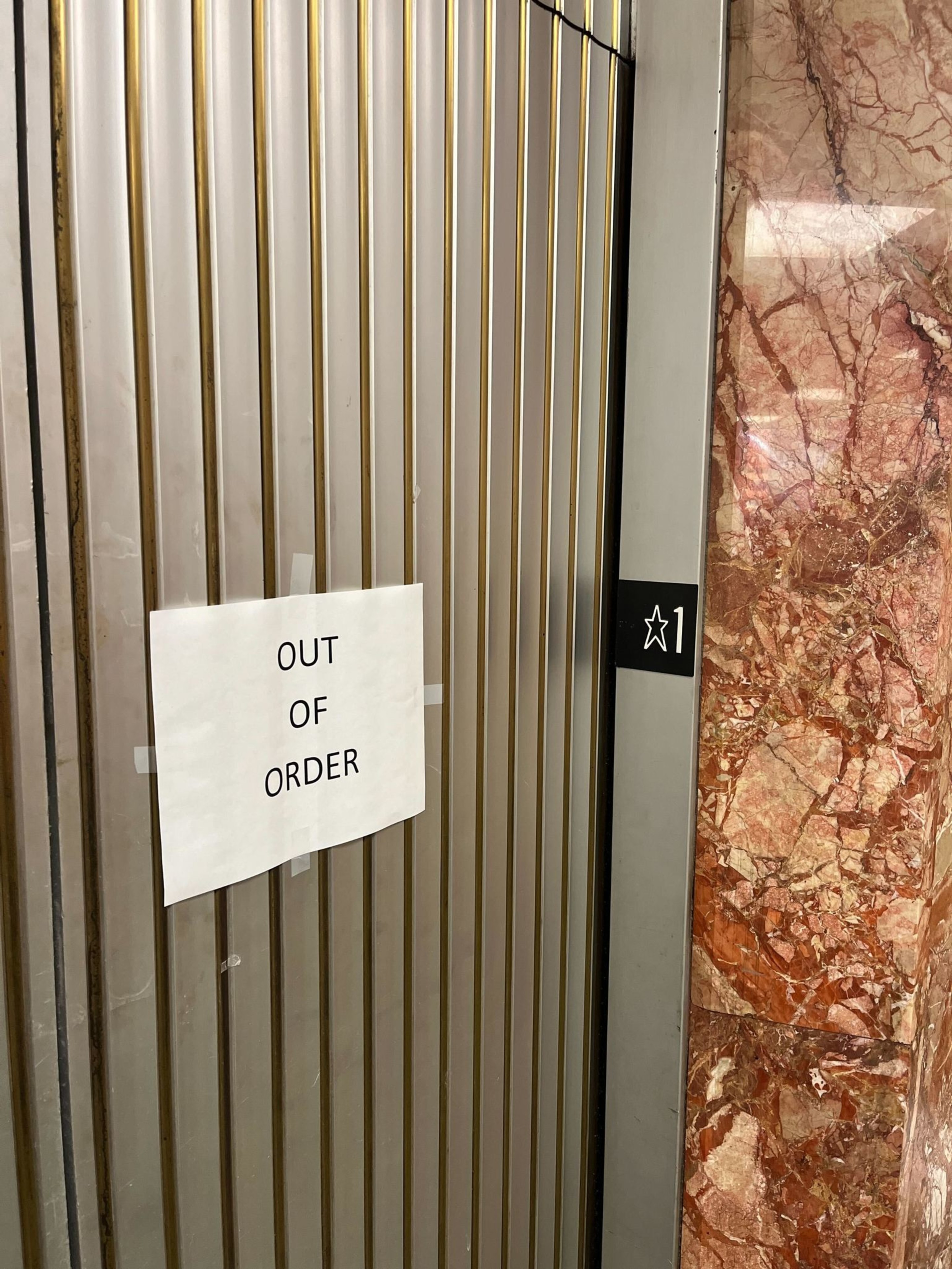

The last five years of maintenance logs from 850 Bryant St. include more than 200 mentions of toilets — overflowing, leaking, or literally breaking apart — and more than 250 of elevators, which frequently break down, sometimes all of them at once.

That’s just the tip of the granite-clad modernist iceberg.

Consider this log entry from Oct. 7: “Freight elevator #6 running constantly no stopping, unable to open doors. Custodian trapped in elevator.”

Or two reports from last year, one on rodent sightings and one asking maintenance to set traps for cockroaches in traffic court.

“Worms are reported coming out of the drain in the shower,” reads one of four nearly identical entries from 2020.

And from the same year: “Replace tombstones in rm.125 fixtures. Light bulb is on fire.”

The Standard reached half a dozen people who work in the building, and all said the elevators are the most consistent source of frustration. Ben Thompson, a clerk who has worked at the courthouse for 18 years, said a maintenance man told him the elevators are so old that certain parts can’t be replaced.

“There are parts of that elevator made by companies that no longer exist,” Thompson said. “From the Eisenhower administration.”

Attorney Garry Preneta heard that building management may “cannibalize” some of the elevators for parts, which a spokesperson for the City Attorney’s office confirmed. Some people follow the “Shape Up (opens in new tab)” tip posted next to the elevators, which advises using the stairs to stay fit.

Tony Vaughn, a court reporter since 1983, said two elevators have been out of service for four years. He added that some of the linoleum floors still have indentations from the days when indoor smokers would stub out cigarettes with their shoes.

“It just looks like crap,” Vaughn said.

The building, which hosted the trial of the Zebra killers and appeared in movies like “Dirty Harry,” was completed in 1960. It has outlasted previous San Francisco justice headquarters: Its immediate predecessor, a tower at the current site of the Hilton in the Financial District, was in use less than 50 years, and the one before that didn’t hit a decade — the 1906 earthquake leveled it just six years after it opened.

After The Standard requested maintenance logs, the San Francisco Superior Court issued a statement announcing progress on plans to replace the building. The court said it is figuring out how to pay for the project and will request state funding for the 2026-27 fiscal year.

“The building is more than 65 years old, and it is plagued by a bevy of structural and mechanical issues,” Anne-Christine Massullo, the Superior Court’s presiding judge, confirmed in the Oct. 31 release. “The HOJ has outgrown its useful lifespan.”

Architectural preservation consultant Chris VerPlanck in 2015 wrote a 200-page “historic resource evaluation” of the Hall of Justice. His conclusion: The building needs to go.

“We’re pretty good at building things but not at maintaining things in this country,” VerPlanck said. “You look at a lot of public infrastructure in California, and it’s trash.”

In 2017, the Judicial Council of California gave the courthouse a “high-risk” seismic rating, saying it was unlikely to withstand a big earthquake. Thompson described the defunct concrete jail upstairs from the courthouse as “a cinderblock atop a house of cards,” just waiting to tear through the building when an earthquake strikes. VerPlanck said the fact that the building was constructed on marshland doesn’t help.

Also in 2017, sewage leaked (opens in new tab) from one floor to another, prompting the district attorney’s office to pack up and move. The Board of Supervisors and then-Mayor Ed Lee called for the building to be replaced, and Naomi Kelly, the city administrator at the time, said she wanted it empty by 2019.

Five years later, Kelly’s successor echoed the warnings.

“It has become increasingly clear that the interim repairs and fixes are not enough,” City Administrator Carmen Chu said in the court press release. Lily Moser, a spokesperson for Chu, said her office has helped six departments move out of the building since 2008.

The problem, Moser said, is that the building can’t close until the courts relocate, and that’s not up to the city — it’s up to the state. She added that she was happy to see that the Judicial Council of California had included a timeline for the courthouse in its most recent report (opens in new tab), identifying the construction of a replacement as a “critical need” project.

Despite the urgency, there’s no chance construction will begin before 2030. The JCC plans to request funding to design and build a new hall in fiscal year 2029-30, according to spokesperson Cathal Conneely. But before that, it will have to find and acquire a site — a lengthy, expensive process in itself.

In the meantime, the courthouse will continue to offer a less-than-luxurious experience to visitors, the type one former staffer does not remember fondly.

“The stench of the building is offensive, and I would say toxic,” said Cynthia Marcopulos, who worked in the building between 1981 and 2009. “If you are allowed into the back hallway, it is a smell you will never forget.”