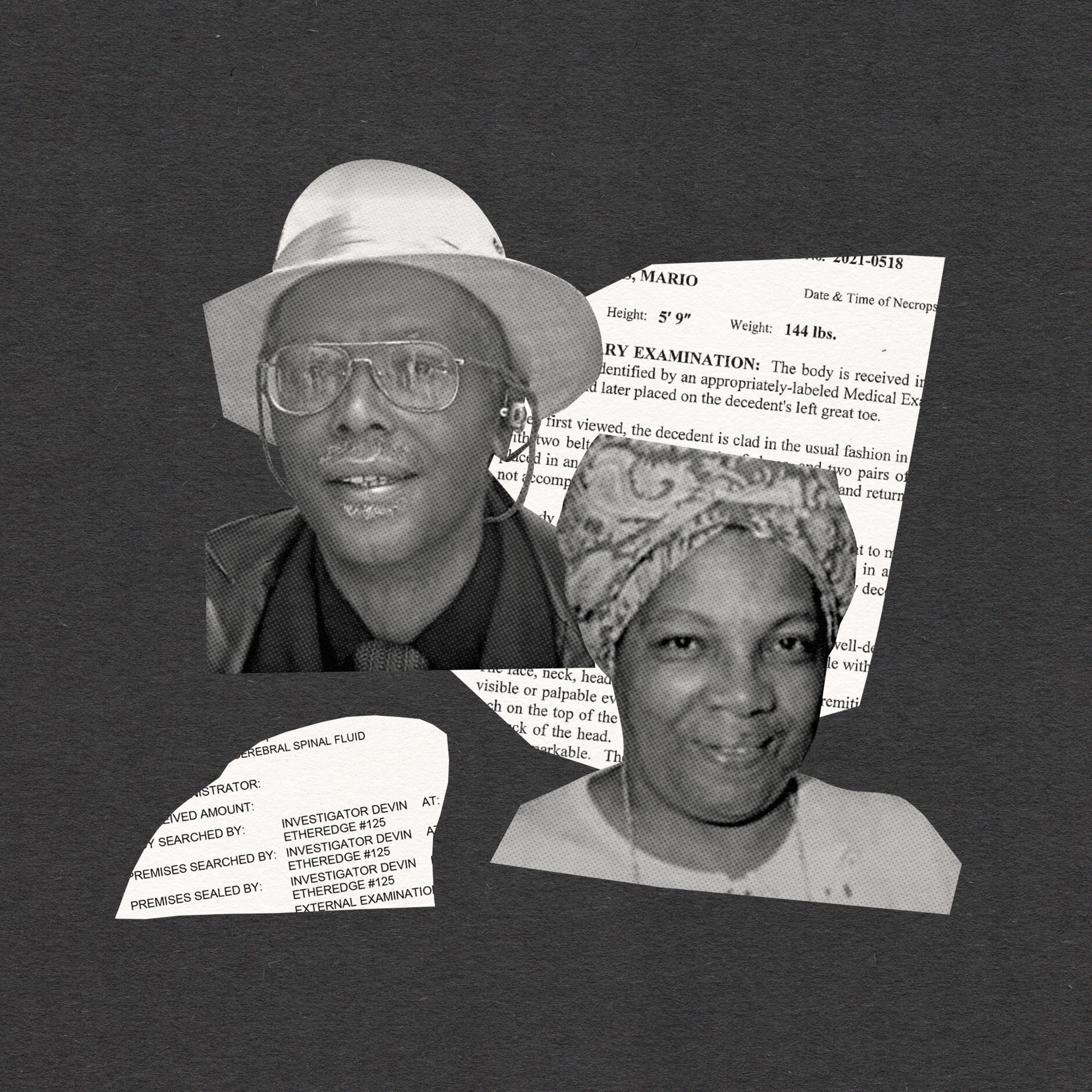

Mario Rogers was 6 when his family moved to San Francisco’s Fillmore neighborhood in the early 1960s. Before long, his mother, storied activist Mary Helen Rogers, was blocking bulldozers, trying to save the city’s Black enclave from destruction. She didn’t succeed: Thousands of the young family’s neighbors were displaced by one of the largest redevelopment projects on the West Coast.

In the ’70s, as a teenager living in a neighborhood that was a shadow of its former self, Mario experimented with cocaine and pills. Despite growing up to be a talented speaker and writer, he was dogged by drug use for the rest of his life. He fell in and out of homelessness, bounced between jobs, and eventually moved into a pandemic-era shelter hotel in SoMa.

He died there in March 2021, at 64, of a fentanyl, cocaine, and heroin overdose.

“My mother stood in front of those bulldozers to stop them from tearing down homes that people were in,” his sister Patricia Rogers said of her family’s activism, which contributed to the creation of more affordable housing. “Mario could have done that. That’s how brilliant he was. … But with the addiction, it just floated away.”

Mario was one of at least 410 Black men of his generation to die of an overdose in San Francisco from January 2020 through October 2024. It is the continuation of a grim trend: For decades, members of that generation across the U.S. have suffered the most from wave after wave of deadly drug crises.

Black men born from 1951 to 1970 have died of overdoses at a higher rate than any other demographic group in dozens of U.S. counties, according to findings from an investigation by The Standard, The Baltimore Banner (opens in new tab), The New York Times (opens in new tab), and Stanford University’s Big Local News. The Standard is collaborating with them and seven other newsrooms to report on this pattern.

The disparity is greater in San Francisco than in all other major cities: Black men in this group have represented 12% of all overdose deaths in the past four years, despite making up less than 1% of the population. They are nearly 32 times more likely to die of an overdose than the average American.

However, the crisis among older Black men hasn’t garnered the attention drawn by younger white victims. Long disillusioned by anti-drug policies that caused destruction in their neighborhoods through heavy-handed policing and mass incarceration, some Black community members remain wary of shining a spotlight on the crisis. But for others who’ve suffered the loss of relatives, friends, and neighbors, the silence has gone on too long.

“The brothers, the young men that I knew back then, they were handsome men. They’re gone now,” said Rogers’ sister Angela Faith McPeters. “They’re all on crack, hooked on heroin, dying from the fentanyl that’s been put into that community. People are laughing at them because they’re Black people: ‘Who cares? You know, who really cares about the Black man killing himself off?’”

‘Our community … it’s gone now.’

Public health researchers and community members who have tracked the overdose crisis among San Francisco’s older Black men point to several factors that have put this generation at heightened risk from deadly drugs.

Black San Franciscans born in the 1950s and 1960s watched as their community was forced out of the city when racist redevelopment policies gutted their neighborhoods.

'The brothers, the young men that I knew back then ... they're gone.'

Angela Faith McPeters

In the 1980s, when they were in early adulthood, crack cocaine and heroin swept across the Bay Area. Richard Beal, director of recovery services at the Tenderloin Housing Clinic and a member of the cohort himself, said many Black men of this generation were introduced to drugs during the crack epidemic. As California carried out its war on drugs, Black people were imprisoned at a higher rate (opens in new tab) than other racial groups and sentenced more harshly (opens in new tab) than white people.

Some of Beal’s peers landed multi-decade prison sentences for crack cocaine possession. Those people emerged from incarceration to find a transformed San Francisco. Their community had disappeared, and drugs were even more accessible and dangerous.

“They lost decades, and now they go back to a city where they might not have any relatives left,” Beal said. “They get out of jail 20 to 30 years later, and they’re putting fentanyl in the crack. They’re putting fentanyl in everything.”

Cocaine was a contributing factor in more than two-thirds of fatal overdoses among older Black men — double that of white and Latino men. Most of the time, those Black men had fentanyl or heroin, in addition to cocaine, in their systems when they died.

A study by the Department of Public Health found 59% of Black people who survived opioid overdoses in San Francisco were stimulant users who ingested fentanyl by mistake.

As the war on drugs raged through the 1980s and 1990s, San Francisco’s economy underwent a major shift; working-class jobs evaporated as the computer revolution took hold.

San Francisco became an international tech hub. But relatively few Black residents benefited from the business management and computer industry jobs that have flooded the market since the 1980s; Black San Franciscans today are less likely to work in either sector than other racial groups.

That left Black locals to grapple with skyrocketing unaffordability, without reaping the benefits of the dot-com wealth flooding the city.

In 2023, the median income for Black households in San Francisco was about $47,000. That’s less than a third of the white household median of $158,000 and less than half the overall median of $127,000.

White, Asian, and Hispanic households in San Francisco earn more than the U.S. averages for those groups, but Black households in the city earn less than their peers nationwide.

Phillip Coffin, the city’s director of substance use research, said his studies have found that a disproportionate number of older Black men who died of overdoses were homeless or recently housed, leading him to believe the city’s death disparity is caused largely by economic factors.

Black San Franciscans who weathered the economic headwinds to stay in the city have found themselves isolated in the communities they grew up in.

McPeters described arsonists attempting to burn the family’s Webster Street home in retaliation for their activism. She recalls cranes lifting up her neighbors’ Victorian estates and heaving them onto the backs of trucks to be taken to other neighborhoods, where they sold for millions.

“When I’m driving through the area, it brings tears to my heart,” she said. “All of that area within there was like our community. It’s gone now. If it’s not torn down and abandoned, it’s gone.”

'When I'm driving through the area, it brings tears to my heart.'

Angela Faith McPeters

McPeters, who moved to Texas, said several of her nine brothers struggled with lifelong drug addiction while living in San Francisco. She noted that Mario’s habit seemed like a coping mechanism.

She later learned that when Mario was 14, around the time he started using marijuana, then heroin, he was sexually abused at a local youth center.

“If anything brought him back to that point, he went and got high,” McPeters said. “Something tragic happened in his life, and he started using drugs.”

Mario’s twin brother, Mark Anthony Rogers, also fatally overdosed on cocaine, in March 2023.

His body was found inside a low-income housing complex named after his mother, according to the death report.

‘Fentanyl doesn’t discriminate’

Moshaun Smith, who grew up in the historically Black Bayview neighborhood, smoked cocaine-laced cigarettes for roughly 20 years, he said. He worked as a janitor and washed cars while living with his mom in the neighborhood.

In November 2023, a neighbor discovered the 54-year-old falling out of his car, and an ambulance rushed him to the hospital. When he woke, a doctor told him he’d nearly died from a fentanyl overdose. For the first time, he seriously considered seeking treatment.

From 2020 to the time of Smith’s brush with death, hundreds of Black men around his age fatally overdosed in the city. But because Smith always bought his drugs from the same dealer, he never thought his cocaine might be cut with fentanyl.

“It’s a lot of deaths going on, and people still don’t know,” Smith said. “Fentanyl doesn’t discriminate at all; it happens to any and everybody.”

Such stories — years of substance use before seeking treatment — aren’t uncommon among drug users, according to experts. For Smith’s peers, a deep and well-founded distrust in the healthcare system, stemming from a history of discriminatory medical practices in public health, sometimes adds to the hesitation to seek help.

“Our generation still doesn’t trust the healthcare system,” Beal said. “Black men would rather get their drugs from the street than go and get a prescription drug from a doctor.”

The issue is exacerbated by a lack of representation of the community in public health decisions, according to Cedric Akbar, forensic director for Westside Community Services, a city drug rehab nonprofit.

“They never talk to us,” said Akbar. “They make decisions about us and then say we have to comply to it.”

Westside Community Services is one of the few Black-run drug rehab nonprofits in the city. Smith, who has been sober for a year and a half, credits its programs with saving his life.

Hillary Kunins, the city’s director of behavioral health, said officials are expanding their fleet of peer responders — people with lived experience of addiction — to help earn the trust of older Black men, with the goal of getting them into treatment. She said a new program called “The Shop,” modeled after a barbershop, will aim to do so through the power of social interaction.

The health department said its also holding regular meetings with members of the Black community, increasing outreach in historically Black neighborhoods, and partnering with faith-based organizations.

‘We’re not going to quit’

If there’s one institution that community members believe has the trust and track record to make a difference in this crisis, it’s the church.

During the Covid pandemic, churches assisted in increasing vaccination rates (opens in new tab) in Black neighborhoods across the country. Pastors partnered with public health agencies to dismantle distrust in the vaccine as Black people died from the virus at disproportionately high rates.

Yusuf Ransome, a public health researcher at Yale School of Medicine, said he envisions churches playing a similar role in fighting the overdose crisis, citing a study (opens in new tab) he conducted that shows a correlation between church closures and poor health outcomes in Black neighborhoods during the pandemic.

“The church initially started off with a healthcare mission,” Ransome said. “As a social institution, there isn’t any [other] that has picked up the slack.”

In San Francisco, Black churches have struggled in recent years as the group’s population has plummeted alongside a widespread decrease in religious participation. Historic Black faith institutions in the Fillmore, once visited by influential civil rights leaders, have been forced to cut programs that provided a safety net for struggling community members.

Pastor Mervin Redmond of St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church in the Bayview said his institution stopped its weekly meetings for people suffering from addiction at the onset of the pandemic, just as overdose fatalities climbed to record highs.

'Only God can heal weariness and spiritual brokenness.'

Cedric Akbar

“It’s like one step forward, two steps back,” Redmond said. “But we’re not going to quit.”

Combatting the stigma of addiction within many churches remains an obstacle. Akbar said he’s had little success convincing Bayview churches to open drug rehabilitation programs.

“When a person is spiritually broken, housing or a drug program cannot fix the problem,” Akbar said. “Only God can heal weariness and spiritual brokenness.”

The path forward

Among Black service providers, and the city as a whole, there is disagreement on the path forward.

Maurice Byrd, a clinical supervisor at the Harm Reduction Therapy Center, contends that the community would benefit from more education about lifesaving measures such as fentanyl test strips and naloxone, an opioid antidote.

He said these methods of reversing overdoses, because they fall under the label of “harm reduction,” have developed a stigma in the community.

“Especially the older Black community has what I call a healthy distrust in harm reduction. It’s seen as a white thought coming into the Black community,” Byrd said. “But I think all people hear when they think about harm reduction is the permission to use drugs, which is completely inaccurate.”

Akbar counts himself among the skeptics of harm reduction, arguing that the practice enables drug use. He contends that public funds would be more effectively used on rehab programs. And in some cases, he believes, people should be forced into treatment if they repeatedly refuse.

“You’ve got a group of harm reduction and progressive people who say they want to take care of the poor people, but basically what they do is keep them like that,” Akbar said. “That was the reason for me to get involved in this, because I got tired of seeing my people being used as little puppets and not getting any better.”

But many agree there needs to be a more widespread acknowledgment and understanding of the deadly epidemic in order to combat it. Akbar said most of his Black clients are reluctant to admit they’re addicted to fentanyl. Even family members of some victims are unwilling to recognize their loved ones died of an overdose.

“Most of the Black people I know, you don’t go tell your business to nobody,” Akbar said. “I think the whole community is in denial.”