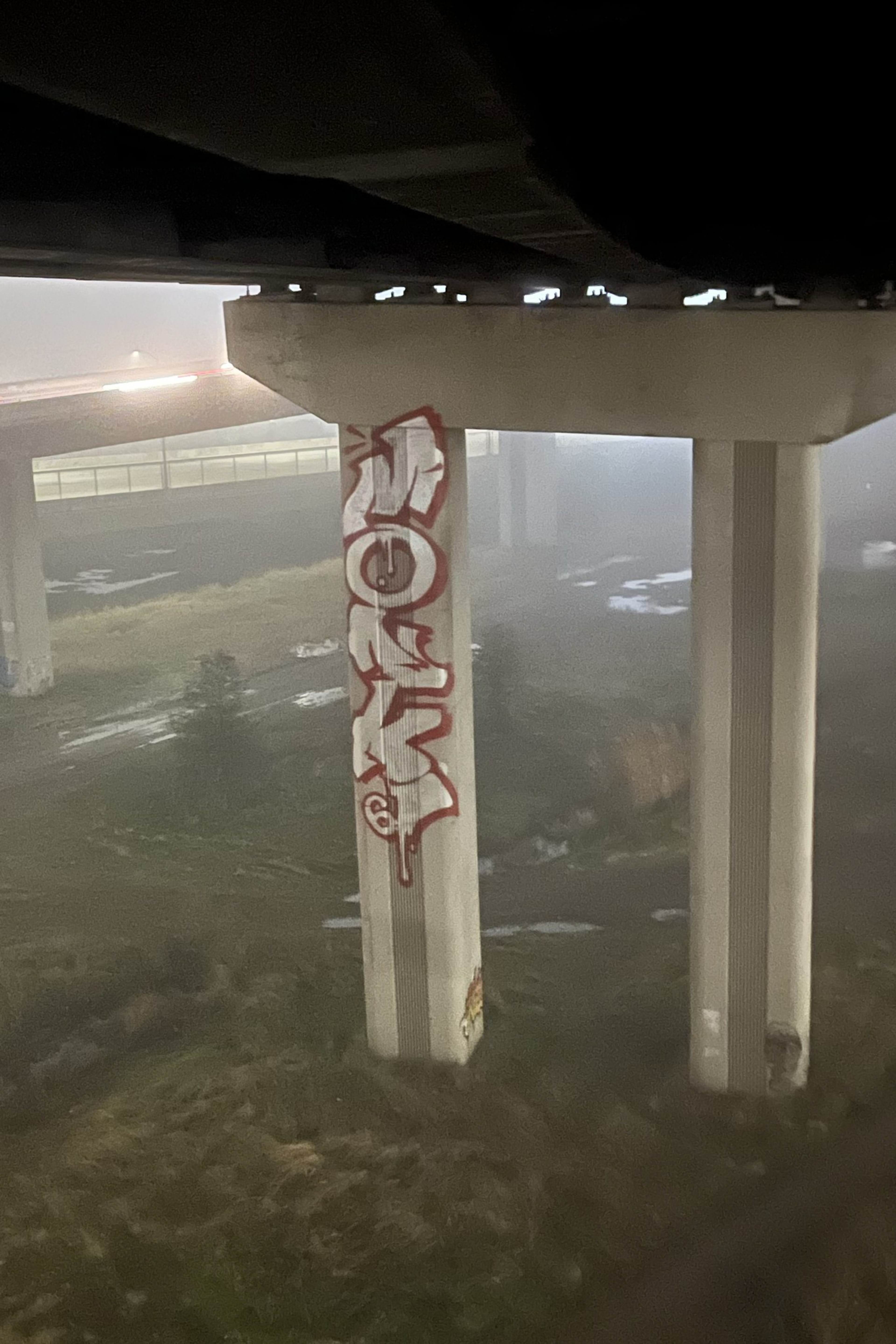

We hopped a fence to get in, running stooped and silent through piles of trash and discarded paint cans. Caltrans work trucks behind us shone their lights through the muck, the tall grass alive with the croaking of frogs, the scent of fresh mud and diesel fumes. We moved ghostlike through thick winter fog.

I regretted wearing my new sneakers.

The maintenance walkway shook as cars rumbled on the freeway overhead. We tiptoed, hunched against the wall, until we came to a steel support cutting diagonally across our path. My guide wriggled under it.

Army-crawling along the sharp, perforated metal, I could see the lights of semi trucks streaking by on the onramp 50 feet below.

“Don’t look down,” my guide joked.

Unlike me, he had been up here before.

We were beneath West Oakland’s Interstate 880 on the edge of the MacArthur Maze, where the Nimitz Freeway, Interstate 80, and Interstate 580 meet. My guide has been coming here for decades, painting Caltrans pillars and cement traffic barriers. He said he recently rappelled down one of the gargantuan supports holding up the freeway to paint a memorial piece. “Allegedly,” he added, grinning.

Up on the walkway, he left a small tag in the freeway’s guts. Then he exhaled and took in the view.

“This is it,” he said.

‘Don’t paint anything that’s gonna ruin somebody’s day’

Graffiti, to some, is a blight or sign of urban decay. It is also arguably the most abundant form of public art in the Bay Area.

It’s free to view, and it’s renewed daily, despite the efforts of city workers and building owners to paint over it. Oakland in particular is a mecca for writers — the term graffiti artists use to describe themselves — with its good weather and lax enforcement.

Wag is a writer in her 20s, born and raised in deep East Oakland. (She and other writers who spoke to The Standard withheld their real names for obvious reasons.) She said cops turn a blind eye to graffiti because they have bigger fish to fry.

“There’s murders, there’s car theft, there’s home invasions,” Wag said. “So I think the least of their worries is people painting on things.”

Oakland police data show about 120 reports of vandalism, which includes graffiti, in the past four weeks (annual data are not available). The city did not say how much money it spends painting over graffiti.

Across the bay, San Francisco spends about $20 million (opens in new tab) a year on graffiti cleanup and requires property owners to remove tags within 30 days. In a September 2023 survey of restaurant owners, the Golden Gate Restaurant Association found that 97% had experienced vandalism in the previous month.

Also in 2023, police assigned (opens in new tab) an officer to investigate graffiti full time. We asked the San Francisco Police Department about the impact of that officer’s work, but a spokesperson has yet to respond. Laurie Thomas, director of the restaurant association, said she was pleased that the district attorney’s office is prosecuting vandalism cases.

When asked whether graffiti removal would be a priority for his administration, Mayor-elect Daniel Lurie said his agenda includes “ensuring the SFPD Graffiti Abatement Unit has the tools it needs to effectively investigate and prevent acts of vandalism that harm neighborhoods and unfairly impact small businesses.”

But some writers say that characterization doesn’t describe them. Vince Vert, who writes graffiti and authors comics, said he avoids tagging independent stores. He said he adheres to a principle laid out by Oakland graffiti writer and fine artist Jurne (opens in new tab): “Don’t paint anything that’s gonna ruin somebody’s day.”

“I always try to follow that rule,” Vert said.

He and other writers maintain that nobody cares about beige municipal walls, dumpsters, electrical boxes, and highway infrastructure until somebody tags them.

“If you think about the highway, BART walls, they were used to disenfranchise the Black community and segregate the city (opens in new tab),” said Vert, who noted that he is white. “It’s appropriate for people to take those spaces back and use them for what they’re passionate about.”

Wag said that, for her, the appeal is more straightforward: “I like writing on shit. I like the adrenaline. I like making people mad. It’s not meant for everyone. It’s meant for the collective.”

But while graffiti requires breaking the law, writers said they do have rules of their own. For instance, don’t start beef to get a reputation, don’t paint over dead writers’ work, find unique spots, and approach the game with humility.

‘You want to be safe behind the glass’

Vert pays his bills as a full-time artist (he sells paintings, comic books, and merch) but still films himself painting highway spots in broad daylight. He moved to Oakland nearly 10 years ago to paint and never left.

“There’s the same amount of people doing it in L.A., but in L.A., there’s gangbangers you have to worry about,” Vert said.

Pemex, a retired Oakland graffiti writer who has transitioned to the world of murals, galleries, and tattoos, said the same.

“L.A. is vicious — cutthroat. New York is cutthroat. The Bay Area is a little more relaxed,” he told me over wonton soup at a late-night spot in Chinatown.

Pemex added that regional styles reflect their climates: Bay Area graffiti, he said, is more hip-hop, more old school, “more bits and doo-dads, boom bap shit.” In other words, more similar to the 1970s New York graffiti showcased in documentaries like 1983’s “Style Wars.” But in L.A., angular gang tags mix with Gothic script, and dripping, multicolored letters blend into one another in intricate wildstyles.

Influenced by both scenes, Pemex’s signatures include “Cholo lettering” and cartoonish bubble letters alike. He knows most people will never care to learn these nuances or treat real graffiti as an art form worthy of study.

“You hate it because you’ve been told to hate it,” he said. “You probably don’t hate it. In fact, you love it when it’s artificially preserved for you in a gallery space with a gold frame around it.”

But the polished, public-friendly “graffiti-inspired” artwork can’t exist without raw vandalism in the streets, he said.

“It’s like the zoo,” Pemex said. “You wanna see the animals, but you want to be safe behind the glass. And it doesn’t fucking work like that.”

Pemex moved to Oakland from L.A. in 2005 and has been painting ever since. These days, he is focused on his collective, Last Ones Left, which creates murals with respected graffiti writers so that others don’t tag them. It’s the only tactic that keeps murals clean, he explained.

Another idea he floated was a harm-reduction approach to graffiti: Let kids paint certain underpasses during certain hours. Would that actually stop them from painting other spots? Not completely, no, but it might help.

“Shit, we’ve tried everything else,” he said.

‘Everybody starts as a toy’

Any underground collective with cultural cachet is bound to attract mainstream attention, and graffiti is no exception. Pemex said graffiti is more accessible than ever. Countless YouTube videos provide drawing instruction, mini history lessons (opens in new tab), scene documentaries, and even language skills. (A video (opens in new tab) called “44 Graffiti Slang Words You Didn’t Know the Meaning To..” has nearly 90,000 views.)

“This was something for hood kids in the ghetto that had no money for art school,” he said.

Now the art-school kids want street credibility. But also, years of isolation and economic anxiety — and the anticapitalist backlash they’ve incurred — have proved fertile soil for subversive street cultures. Doing graffiti, in other words, is a thrilling way to say “Fuck the system.”

“It seems like there’s more of a consensus that not everything should be based around capitalism or making money,” Vert said. “Subcultures that people will never make money from have value in their own way.”

Mario Riveira, a local filmmaker famous for his man-on-the-street interviews (opens in new tab), chronicles these cultures and has produced two feature-length graffiti documentaries: one about Seattle, and one about Oakland. There was a San Francisco doc in the works, but production has paused.

“Shit got hot,” Riveira said cryptically.

The Oakland documentary profiles writers including Wag, Guez, and, uh, Cumrag. It has so far racked up more than a quarter of a million views.

A since-deleted comment on the video criticized the documentary for “showing toys [novices] how to use Etch Bath,” referring to an acid some graffiti writers use to mark glass surfaces. When I asked him about it, Riveira didn’t disagree. Part of what makes graffiti documentaries exciting is that they take viewers inside a famously insular and paranoid culture.

“Everybody starts as a toy,” Riveira said. “You can’t just be the biggest, baddest dog on the street and come out like that.” He added that documentaries like his inspire beginners to improve their techniques and teach them to respect the rules.

More than instruction, though, Riveira said his work is about representation.

“Some see it as art; some see it as vandalism,” Riveira said. “I’m just working with them and telling their story.”

Documentaries, like legal murals and gallery pieces, preserve graffiti for posterity. But the essence of the art form is in its transience.

“You can’t capture that magic,” Pemex said. “You can’t bottle it. All you can do is stand by in awe.”