Welcome to The Looker, a column about design and style from San Francisco Standard editor-at-large Erin Feher.

We should not be here. Key Jo Lee, chief curator of the Museum of the African Diaspora, has spent the last few months explaining why the domestic spaces of Black people — specifically, women — are sacred and should not have to function in a productive or capitalist capacity … such as promoting an exhibit.

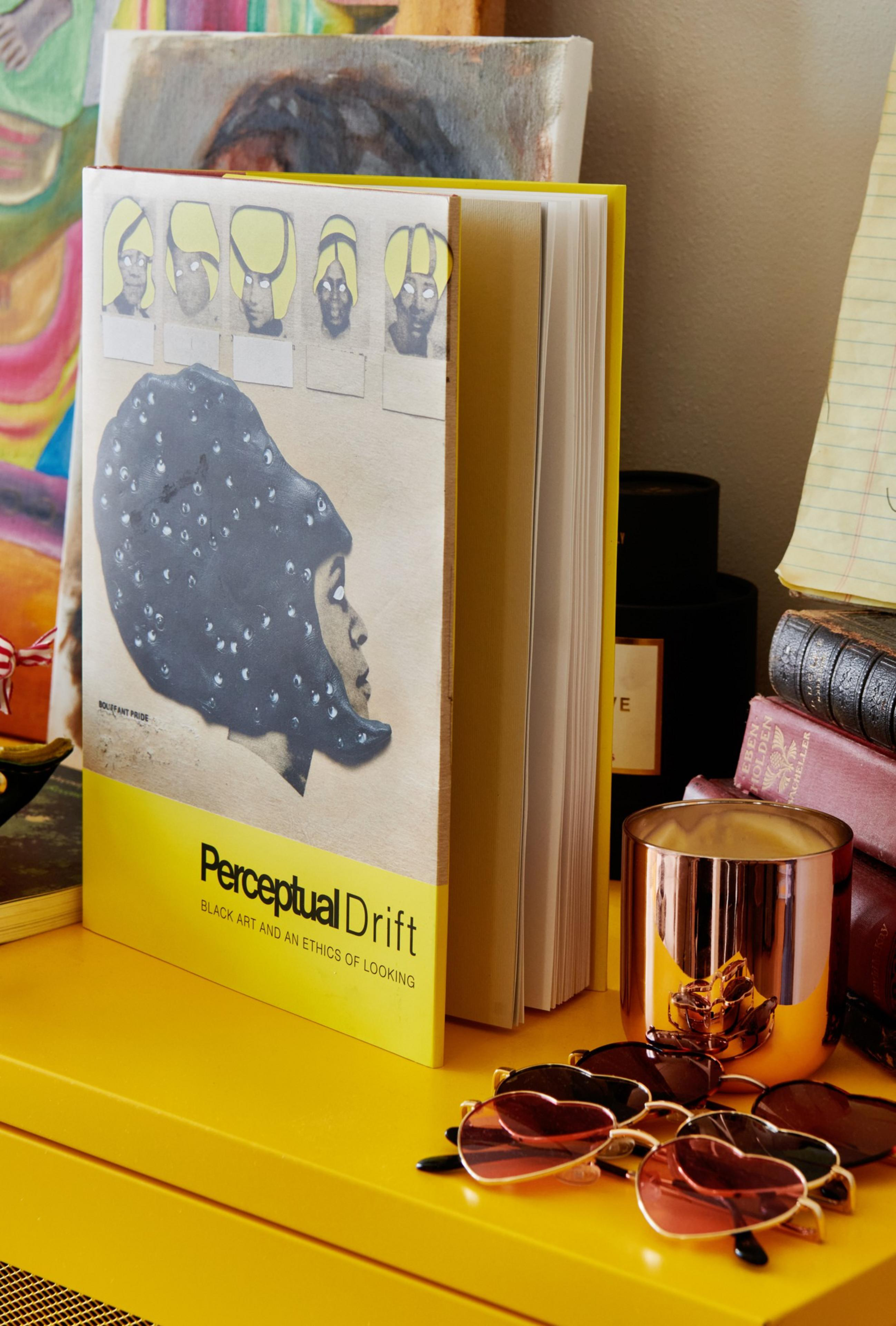

Yet, here we are, inside Lee’s historic East Cut loft — her sanctum — half a dozen scented candles burning, mugs of tea steeping, and her fretting about the boxes in the corner she hasn’t found a moment to unpack. She’s been too busy with her latest exhibit, “Liberatory Living: Protective Interiors & Radical Black Joy,” MoAD’s first design show, which ends Sunday, at which point the museum will close for six months of hibernation and a design refresh.

The expansive show features furnishings, lighting, ceramics, and even wallpaper, all by contemporary African diasporic designers and highlighting the notion that Black residential interiors should “serve as sites of care and rest.”

We both take a moment to appreciate the irony.

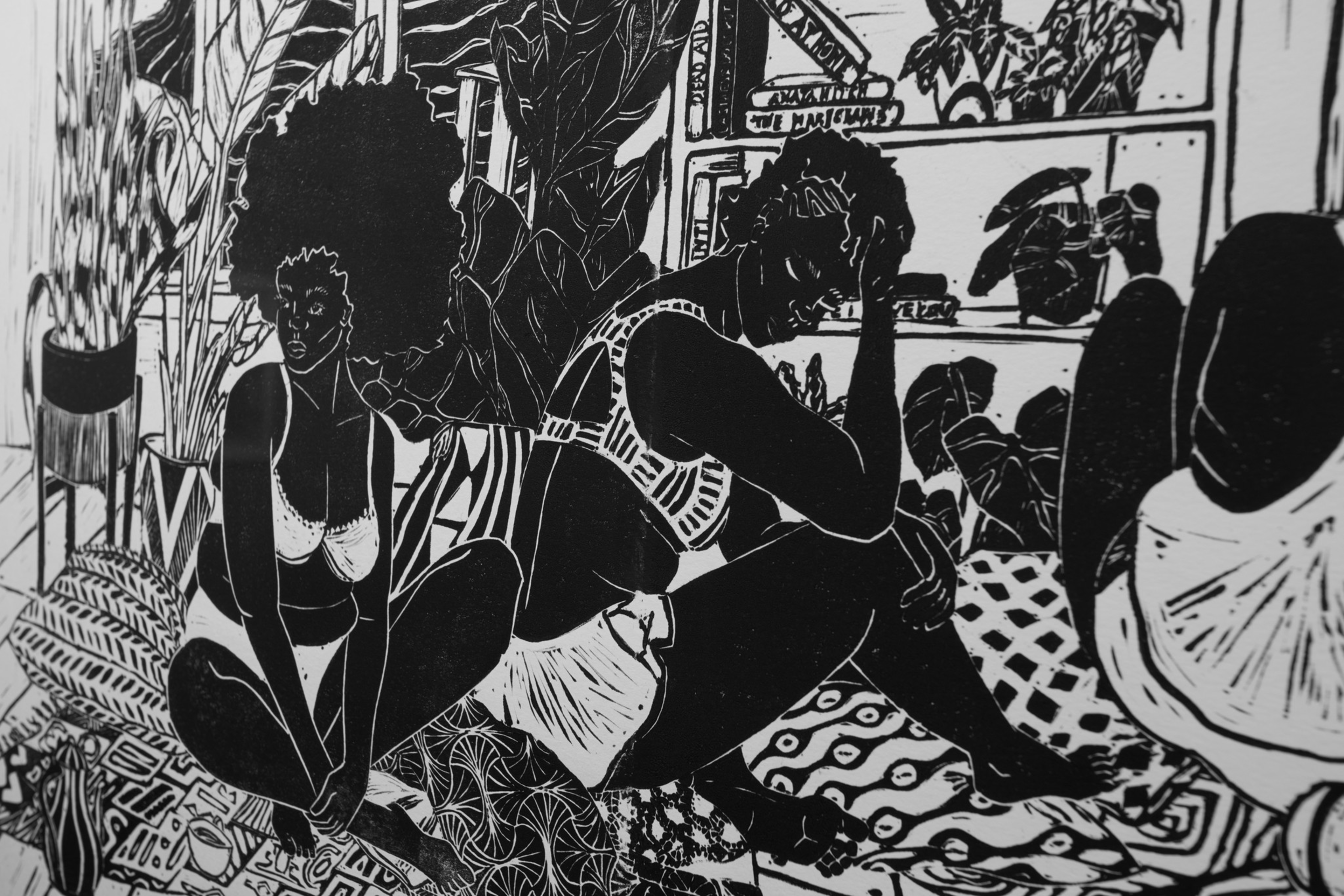

Lee’s specialty is inspiring people to slow down and think about the contrary or complicated. She has worked in museums — first at Yale, where she earned dual master’s degrees in art history and African American studies, then as a curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art — for well over a decade. She believes that looking at art requires close and deliberate attention, the kind that is atrophying in people by the second.

“We just have to build muscle memory for it,” she says.

Lee bubbles over with a deep knowledge of history and art, yet, at 51, still vibrates with the passion and curiosity of a grad student. “The reason I’m always telling people to slow down and look at art is because I think we all need to slow our pace. We’re missing so much. And shit is blowing up because we’re rushing around and not paying close enough attention.”

“Liberatory Living” was her response to this fast-paced grind culture, and to the last decade of society turning to Black women for answers, education, and action. “Instead of thinking about, Where are we going to do some revolutionary work? Where are we going to make more stuff? I’m like, where are we going to sit down?”

Where Lee sits down is in this beautiful loft in the century-old Sorg Printing Building, which was converted to residential units in the 1990s. Though she is excited by this opportunity to show people where she spends her time when she’s not at the museum down the block, her office/walk-in closet is off-limits. It’s her creative hive — the walls covered in oversize Post-it notes jotted with ideas — a space that belongs to no one but her. I don’t ask twice for a peek.

Lee often zips to work on her bike. | Source: Courtesy of Kelly Marshall

Every nook and cranny of the loft is filled with curated moments of joy. | Source: Courtesy of Kelly Marshall

The rest of the loft is intentionally desk-free, and signs of leisure abound. On the glass-topped dining table is a glamorous ice bucket and cocktail shaker by Shelia Bridges in her signature Harlem Toile, a tongue-in-cheek motif that depicts African American stereotypes in the traditional French style. Bridge’s wallpaper version is part of the MoAD show. The bright-yellow sideboards (a Wayfair find) are topped with a pair of antique slippers, a vintage record player, and a bowl of fragrant coffee beans holding the charred remains of incense sticks.

But the star of the living room is a painting of a pair of boxers by New Orleans-based Auudi Dorsey. It was part of the sports-themed exhibition “Versus” curated in the fall by Jonathan Carver Moore at the Four One Nine gallery. “When I first saw Dorsey’s “Gunslingers,” I stopped in my tracks,” says Lee. “Boxing has always seemed strange to me, and I find it hard to watch. But I wanted to understand the dynamic in this painting. I kept coming back. If I’m honest, it is still telling me why I love it.”

Nearby on the kitchen countertop are an electric tea kettle, a hefty cobalt Le Creuset pot, and a collection of pretty jars precisely labeled for salt, pepper, and weed.

A shiny, black cruiser bicycle is parked near the front door, a gold helmet dangling from the handlebars. Lee’s sofa is topped with no less than a dozen overstuffed pillows stacked three deep, all in shades and patterns of quiet ivory.

Up an open spiral staircase is her bedroom, a serene perch that overlooks the main space. A simple pine bedframe from Ikea doubles as a display for beloved textiles. Oat-colored linen bedding is punched up with a rose throw and a pair of boldly patterned pillows. On the wall hangs a vintage Roy Lichtenstein promotional poster from MoMA in New York, which she was gifted for her first apartment back in Philadelphia when she was 21.

The tech in this room is analog: On either side of the bed is a lamp with Edison bulbs (too dim for reading) and a new Vornado table fan, designed in 1945. Each contributes to the feeling of tranquility and offers up few other options than simply lying down and letting one’s eyelids flutter.

“In the galleries, I often ask visitors the question: So, when you think of Black women, how often do you think of them at rest?” says Lee. In “Liberatory Living,” she is particularly drawn to a triptych of paintings by Oakland artist Chantal Hildebrand that depicts Black women languid in a tub or wrapped in towels, drowsy and soft, limbs akimbo. She wants these scenes to be a part of what people think of when they think of Black life.

“It doesn’t mean that you have to sponsor my day off,” says Lee. “It just means imagining a place in which we are not the creators or destroyers of the world.”