Like she did every Friday, Silver Wiesler woke at 6:30 a.m. in her family’s Victorian home in Bernal Heights. She washed her face and picked an outfit for her day at Alvarado Elementary School, settling on a pair of pants that matched her American Girl doll’s, and a white sweater with a blue-eyed cat. She kissed her mom goodbye before she and her little sister, Evening, scrambled into their dad’s Toyota Prius and headed to a nearby coffee shop to look over their homework before school.

That would be the last time Silver, who was 8, and Evening, 5, would see their house and almost everything they owned. An hour after they left, it all burned down.

Eight years later, in February 2025, the Wiesler sisters walked into a makeshift classroom in Santa Monica to share their story with a group of 8-year-olds who had just lost their school building and, in some cases, their homes, in Los Angeles’ devastating fires.

“ While people were giving us toys and clothes, we didn’t really know what to do with all the big feelings we were having,” Silver, now 16, told the kids, clutching a stack of blank journals. “We wanted to make sure you guys had the same opportunity that we did with our recovery process.”

She passed a journal to each child.

What started as a coping mechanism for two heartbroken little girls and their mom has become an act of radical empathy, connecting survivors and providing an outlet for young fire victims to express their pain and loss. In 2017, Silver and Evening created the Fire Journal Project, which would lead them to donating nearly 5,000 journals to survivors young and old throughout California.

And it all started with three words: “Dear new friend.”

A freak accident

It was 8 a.m. on Sept. 23, 2016, when someone pounded on the Wieslers’ front door to alert Silver and Evening’s mother, Samantha. The fire had been spreading inside the walls of the family’s four-story house on Prospect Avenue. A menacing plume swelled above the roof, but there were neither flames nor smoke in the rooms.

After sending her daughters and husband, JJ, off for the day, Samantha was feeding her infant boy, West, and getting ready to head to work when she heard the banging on the door. A day laborer told her in Spanish that the home was on fire. In the commotion, she thought the stranger must be mistaken. Her house couldn’t be burning — she was inside it and sensed nothing. But the man insisted, so she stepped out to indulge him.

“He was a good samaritan, or an angel. I don’t know,” Samantha recalled. “Just someone who saw something scary happening and took action instead of just walking past.”

Even a breakneck response from the San Francisco Fire Department wasn’t enough to save the Weislers’ home. Samantha grabbed only two things — her son and her bag, before firefighters chainsawed part of the roof off and doused the house with water. In the process, two surrounding buildings were damaged and one firefighter was injured.

Farmers Insurance determined the cause of the fire to be a furnace malfunction — it was no one’s fault, just a freak accident.

For Samantha, the event didn’t fully register at first: the total loss of their home of 15 years. It was where she gave birth to all three children. It was a home filled with quirky, handmade furniture, musical instruments, scribbly drawings, the wedding dress she was saving to pass down to her daughters. Samantha, J.J., and the kids would start their recovery journey with only the clothes on their backs and a few precious items, like stuffed animals the firefighters rescued at the last minute. They’d need a place to stay, clothes, food, diapers, hygiene products — everything that makes a life.

But that day, the girls, at school, were blissfully unaware of their loss. When Samantha arrived early to pick up Silver from her after-care program, the third-grader noticed white spots on her mom’s favorite boots. “What’s wrong with your boots?” she asked. “We need to talk,” her mother responded. “That’s actually drywall, from our house.”

The details of this conversation are branded in Silver’s memory eight years later. She recalls the San Francisco community rallying around her family in the first weeks after the disaster. Friends and neighbors organized a meal train. One neighbor offered his empty apartment for the first week, free of charge.

But it was the loss of the little, everyday things that was most disorienting for the girls. “ I was so concerned about my American Girl doll and her pants,” Silver recalled. “Now I have my pants and I don’t have the doll. Who am I gonna match with?”

Beyond the feelings of loss, Silver was struggling with the reactions of some of the adults in her life. “Everything is going to be alright,” they would say. She wished they would instead acknowledge that it wasn’t. “Everything was not OK,” she said. “ I had just lost everything that I owned. I didn’t know how to process this.”

One donation stood out to Silver among the piles of clothes and toys: two empty journals, one for her and one for Evening. They didn’t know it at the time, but these items would put the sisters on a path to healing, and then onto something bigger.

Ambiguous loss

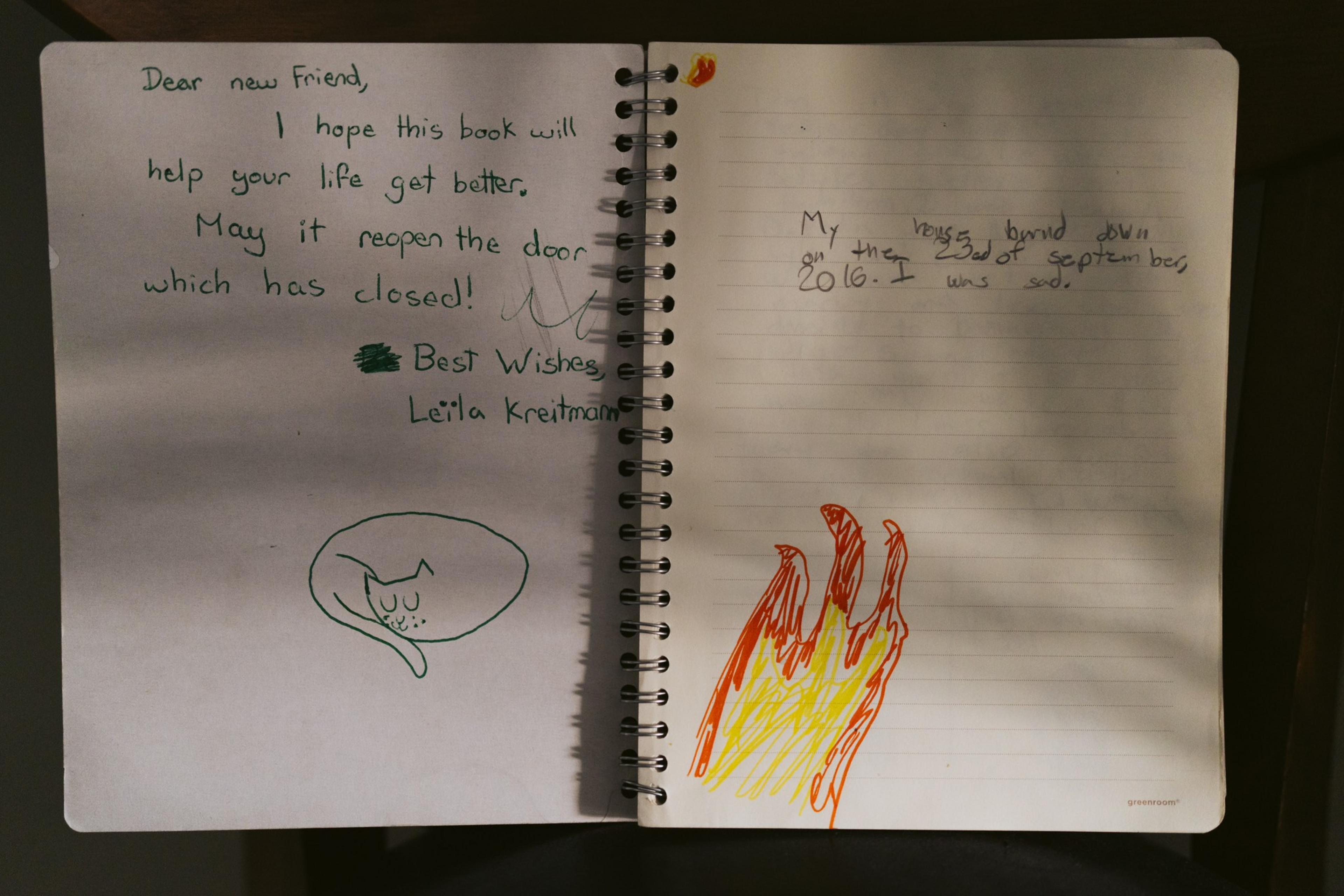

The simple lined notebooks came from an older girl whom they hadn’t met, Leïla Kreitmann. On the inside of the cover, she had written a brief message: “Dear new friend, I hope this book will help your life get better. May it reopen the door which has been closed!” Under the note was a hand-drawn picture of a sleeping cat.

“I always thought about the girl who wrote it and how she was my friend, even though I never met her,” Silver said.

Unlike every other donation, the journal wasn’t focused on replacing a possession. It wasn’t trying to make her forget or displace her old life. Instead, it gave her a way forward. For the 8-year-old, processing the loss of her home looked like orange scribbles in a fire-like shape, accompanied by the words “I am sad.” Evening, who was in kindergarten, drew pictures of the burning house and wrote a list of the things she still owned (the lamb she fell asleep with) and things she had lost (a dollhouse). This felt good. For both girls, having a sense that another kid — a stranger — knew they might need this outlet made a difference.

Dr. Pauline Boss (opens in new tab), professor emeritus in family social science at the University of Minnesota, said there are unique challenges to recovering from the loss of a home. Once urgent needs are addressed and media attention is redirected, the routines of school and work are expected to resume as usual. But the lack of established grieving rituals — there is no funeral for a dead house — can leave survivors in limbo. To describe this phenomenon, Boss coined the term “ambiguous loss.” One antidote? Community acknowledgment of the pain.

In October 2017, a little over a year after the Wieslers lost their home, the Sonoma Complex fires burned for almost three weeks, taking 24 lives, destroying 6,997 structures, and causing direct losses exceeding $7.8 billion. Silver noticed the attention her school community paid to the disaster. For as long as the fires were on the news, they were all anyone was talking about.

There was even renewed interest in her family’s loss. During one school assembly, a mom presented the girls with handmade quilts embroidered with their classmates’ handprints and the words “We got you covered.” The kindness moved Silver, but she noticed that soon after, her classmates turned their focus to other things. She, on the other hand, couldn’t stop thinking about the hundreds and thousands of displaced kids in Sonoma.

“ That was what made me realize I had a different experience or interpretation of it than other kids,” she said.

The project

It was during this time that Silver, then 9, and Evening, 6, went to their mom with the idea of distributing journals to fire survivors. Samantha started a crowdfunding campaign (opens in new tab) through GoFundMe that quickly raised more than $10,000. With a little haggling, she was able to purchase 5,000 journals from a company called Guided and created a website (opens in new tab). The girls took photos of their fire diaries and posted them to encourage others.

At that point, the girls hadn’t seen their house since the day of the fire. Samantha didn’t want them to witness the devastation — it felt too violent. So instead of taking the girls to Sonoma to see the fire zone first-hand, Samantha reached out to the Sonoma County Department of Education for help with the distribution of the journals.

Proctor Terrace Elementary in Santa Rosa committed to distributing the journals to students who were directly affected by the fires. The Mark West Union School District took 1,500 journals and gave them to the entire student body, recognizing that children whose houses didn’t burn were also experiencing loss and needed ways to process it.

Tragically, the process repeated a year later, in November 2018, when the Camp fire, the deadliest wildfire in California history, raged for 18 days in Butte County. When they heard the news, the Wieslers were ready. The Fire Journal Project now had a workflow.

Silver, Evening, and Samantha formed an assembly line in their apartment. They had printed stickers with their website name and a QR code, which they had to attach to journals. On the website, journalers could find the Wieslers’ story, photos of the girls’ entries, and other prompts.

Silver remembers fondly the first email she received from a mom whose son had drawn his house in flames. “I was like, wow. That’s, like, something that I did,” she said. “I remember I was so happy. I just wanted to go back to the school and hear everyone’s story.”

Journey to L.A.

On a Thursday morning in the tail end of February, it was sweltering in Los Angeles. The LA River bed was mostly dry. Ducks were hiding in the shade, desperate to get their whole bodies wet in the shallow pools. Samantha and Evening had taken a mother-daughter road trip the previous day from San Francisco, and spent the night at the Kimpton Everly hotel in Hollywood.

Silver flew in late in the evening, after running a track tryout and taking a chemistry quiz. They planned to drive to Pacific Palisades to see the burned-out remains of the schools whose students would be receiving fire journals the following day. Samantha already had a stress headache getting into the car.

Scenes of luxury and destruction were oddly juxtaposed along West Sunset Boulevard. 2Pac’s “To Live and Die in L.A.” was playing on the car speakers. Evening noted that upscale shops, like Lululemon and Erewhon, the trendy organic grocery store, stood intact while homes were charred. Silver had read that some of these businesses survived because landlords had hired private firefighters (opens in new tab)to keep their complexes safe.

Soon, they turned onto La Cruz Drive and reached their first destination: Village School. Large broken branches, hollow metal frames, rubble, pieces of blackened wood — the devastation was complete, save for a stone wall and a metal fence. A sign with silver letters read “Village School, This is childhood.”

Samantha put her arm around Evening as they stared at the remnants. Finally seeing what fire does to a building stirred up raw emotions in the sisters. “ I hadn’t thought about the real feelings that the fire brought up for me,” Silver said. “Being in this environment really brought them back in real time.”

They visited Palisades Charter Elementary School around the corner before the toxic fumes gave everyone a headache, and they headed back to the hotel to begin the familiar journal assembly line. Walking through the detritus of the fire had been heavy, but for Silver, who never saw the remains of her former home, it felt necessary. “Seeing it, walking through, smelling it, getting that headache was something. I feel a lot more mature now and a lot more able to handle it,” she said.

Stuck in three hours of traffic on the way back to the hotel, Samantha had plenty of time to mull over the experiences of the day. She had long resisted taking her daughters to the fire-stricken places where their journals were destined. But she learned she could trust the girls’ reactions. “I would never wish this on anyone,” she said. But losing everything had “provided the kids with an opportunity to discover their own resilience.”

The sisters had built a spreadsheet with schools affected by the fires and planned to visit as many as time would allow on their two-day trip. They donated journals to Marquez Charter Elementary and Palisades Charter Elementary, both of which were destroyed and are sharing facilities with other schools in the area, and to Harvard Westlake, where 50 students and staff lost their homes and another 50 or so were displaced.

In most cases, they would speak to the school principal and maybe a counselor, share their story, get a tour, and drop off journals. They were thrilled to do a good deed but disappointed when they didn’t get to connect with the children who were the intended recipients of the journals. Until they did.

The temporary home of Village School looks nothing like a school at all. It’s now housed in a business park on Broadway in Santa Monica, complete with paid underground parking, a manicured courtyard, and a glass entrance — it screams tech startup rather than elementary school, a far cry from the gorgeous campus in the heart of Pacific Palisades, with old-growth trees and thoughtfully designed outdoor spaces.

Yet, when the Wieslers passed the security kiosk by the elevators, the elementary school spirit conquered the office vibe. Only weeks after the fires, there were whiteboards and posters, colorful artwork, makeshift classrooms with little desks and chairs, and hangers at appropriate heights for little ones.

Head of school John Evans, a Tony Stark lookalike in a gray crewneck Village School sweatshirt and baseball cap, welcomed the Wieslers at the entrance. He was affectionate in a calm, restrained way and listened to Silver’s story of their house fire with a hand over his heart. When she finished, he pulled in Anu Burkhardt, the school’s “information and imagination specialist.”

The fires had taken Burkhardt’s home and workplace, so the Fire Journal Project immediately resonated. “First of all, can I give you all a hug?” she asked. Samantha, who let the girls take the lead, was crying quietly.

An hour and 300 journals later, the Wieslers exited the flashy building, electrified. Silver and Evening had been invited to walk into each classroom impromptu and talk to the hundreds of kids in matching red uniforms about their loss, their project, and about how, eventually, they had started to heal.

The kids had asked questions, smiled, and thanked them profusely for the journals. With each classroom, Silver had become more confident as she addressed the kids and their teachers. She was luminous.

Over lunch that day, a new tone appeared in Silver’s voice. “I felt really fulfilled. That really made me feel like I was actually doing something,” she said.

The realization that there was a place for everything she had struggled to name in the past eight years hit her. She was able to see a small silver lining in the loss of her childhood home — not one any well-meaning neighbor may have offered, but one of her own: As awful as it was, the experience would help her relate to survivors in a way others couldn’t. “It makes me want to work with kids,” she said. “I don’t just want to bring the journal, I want to lead the classroom activities.”

And so, Silver began to dream up a future she was genuinely excited about.