Timothy Simon’s view was almost perfect. From his Bayview hilltop balcony, he could see the downtown skyline, the glistening bay, and the Oakland hills in the distance. But in the foreground, for much of the last five years, was a line of RVs.

He tried everything to have the persistent homeless encampment removed. He pestered cops, filed 311 reports, and lobbied City Hall. But the city’s response to his pleas was often no response at all, he said.

“We’re sitting out here with this beautiful little strip,” said Simon, gesturing to his view of San Francisco’s southern shoreline. “Our issue is, the city wants to keep treating this like an industrial shithole.”

Simon is one of an increasingly vocal group of Bayview residents frustrated with the lack of response to their complaints about homeless encampments.

The city’s response time to these grievances is far slower in Bayview-Hunters Point than in any other neighborhood, according to an analysis by The Standard of reports to the 311 help line. City staff took a median of 14.6 days to close 311 encampment cases in the Bayview last year, nearly 10 times the citywide median of 1.5 days.

The number of 311 encampment complaints skyrocketed citywide last year after a landmark Supreme Court decision freed officials to take a more aggressive approach to removing tents and RVs. In 2024, the 311 system logged nearly 48,000 encampment reports. This year, the city is on track to reach about 58,000, more than double the 2021 total. The pre-pandemic high, in 2019, was 70,000 complaints.

Even with the increased volume of 311 cases, officials managed to respond to reports faster across much of the city. But in the Bayview, the median resolution time quadrupled between 2023 and 2024.

For comparison, the median time to close a complaint in the Marina in 2024 was less than a day. In the Tenderloin, it was 1.8 days. In Portola, it was 6.1 days, second only to neighboring Bayview, with its two-week median resolution time.

Closing out a complaint typically means the city took some action, such as sending outreach workers or police officers. But for 10% of reports in the Bayview, the city let the case languish for a month before automatically closing it out; it then instructed neighbors to submit a new complaint if the encampment was still there. In most other neighborhoods, this happened with fewer than 1% of reports.

The Department of Emergency Management said encampments in the Bayview are often larger and more complex than those in other neighborhoods, frequently involving structures and vehicles, which require a more nuanced approach. The Bayview is home to the highest concentration of people living in vehicles, according to the the city’s quarterly counts.

‘Relegated’ to the Bayview

Bayview residents refute the idea that the slower response in their community is due solely to the complexity of its encampments.

They attest that the neighborhood has long borne the brunt of the city’s ills — from chronic potholes to persistent illegal dumping and hazardous pollution (opens in new tab) — while standing last in line for government services. To this day, about a quarter of Bayview blocks are labeled by the city as “unaccepted,” meaning the Department of Public Works takes no responsibility for their condition.

“This isn’t a planned neighborhood,” said Marsha Maloof, president of the Bayview Hill Neighborhood Association. “You couldn’t live as a Black person anywhere else, so we were relegated to this area. All these years later, we still don’t have a lot of things that would come to a planned neighborhood.”

Warehouses and empty lots make up much of the community, providing refuge for homeless people who would face greater scrutiny in other parts of the city.

In one corner of the Bayview lined with abandoned fields and factories, two homeless migrant families from Honduras live in trailers parked next to each other.

A 1-year-old boy played with toy monster trucks inside one trailer. His father cried as he explained their fears of being towed.

“They would leave us on the street,” said the father, whom The Standard is not naming due to the family’s immigration status. “Every parent seeks the best for their children, but under these circumstances, it is not possible.”

Prior to living in the RV, the family slept on trains and buses, or in a school gymnasium in the Mission, the father said. He said he works in construction but business has been slow due to the rain.

“We came to San Francisco because San Francisco is — well, from what one hears — a sanctuary city that supports immigrants,” the father said. “Not that we are in better condition, because the city doesn’t want us to be living here either.”

Having grown up in poverty or experienced homelessness themselves, several Bayview residents said they empathize with people living on the streets. But they see the city’s response as insufficient and inconsistent.

“Those families deserve affordable housing. I’m all in on that,” Simon said. “But the city just throws money at it so they can have their little atonement. It doesn’t really make certain that the money is being properly allocated and distributed.”

‘A cold day in hell’

The stretch of Gilman Avenue that extends into Candlestick Point, within view of Simon’s balcony, embodies how the city’s well-funded efforts often fail to improve the lives of homeless people and housed residents alike.

Throughout the Covid pandemic, there was a persistent RV encampment along the road. In 2021, people were living out of about 150 vehicles at the Candlestick site, infuriating neighbors, who filed numerous complaints. Officials eventually took action after major flooding in November 2021 left people stranded.

In January 2022, the city opened a triage site in a parking lot at the end of the road where homeless people could live in RVs. The site provided access to showers, bathrooms, and three meals a day — desperately needed resources for people living in vehicles.

The cost of the facility reached $17 million by the time it closed March 3. But that figure mystified clients, who say the food was nearly inedible and the staff unaccommodating.

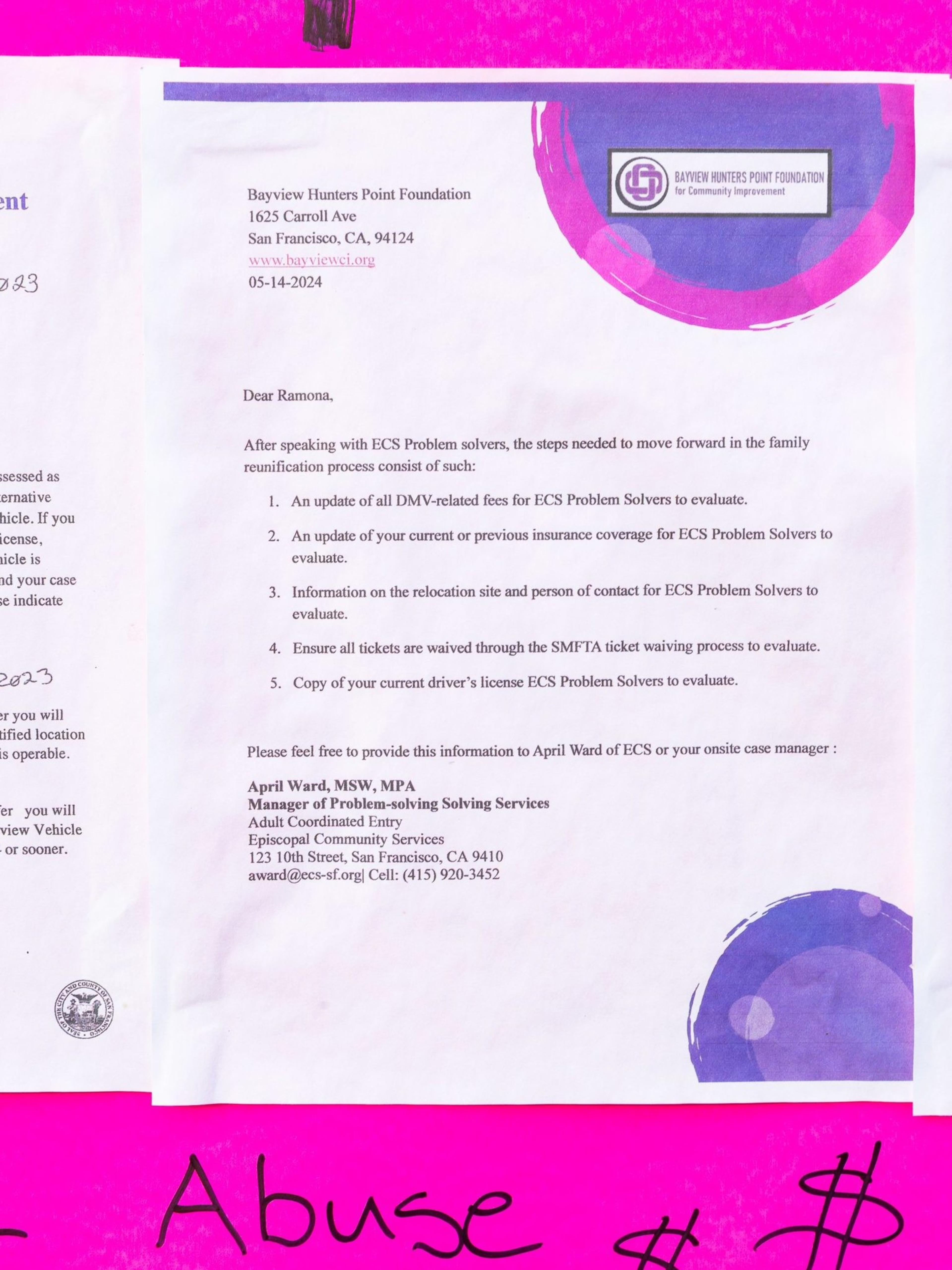

“They make millions while we’re given a bowl of gruel,” said Ramona Mayon, who has lived in an RV for more than two decades. “There’s such a huge gap in the money that’s spent and the services we receive.”

When the city shuttered the site, roughly a dozen people moved their RVs back onto Gilman Avenue. The new gathering quickly drew complaints from locals.

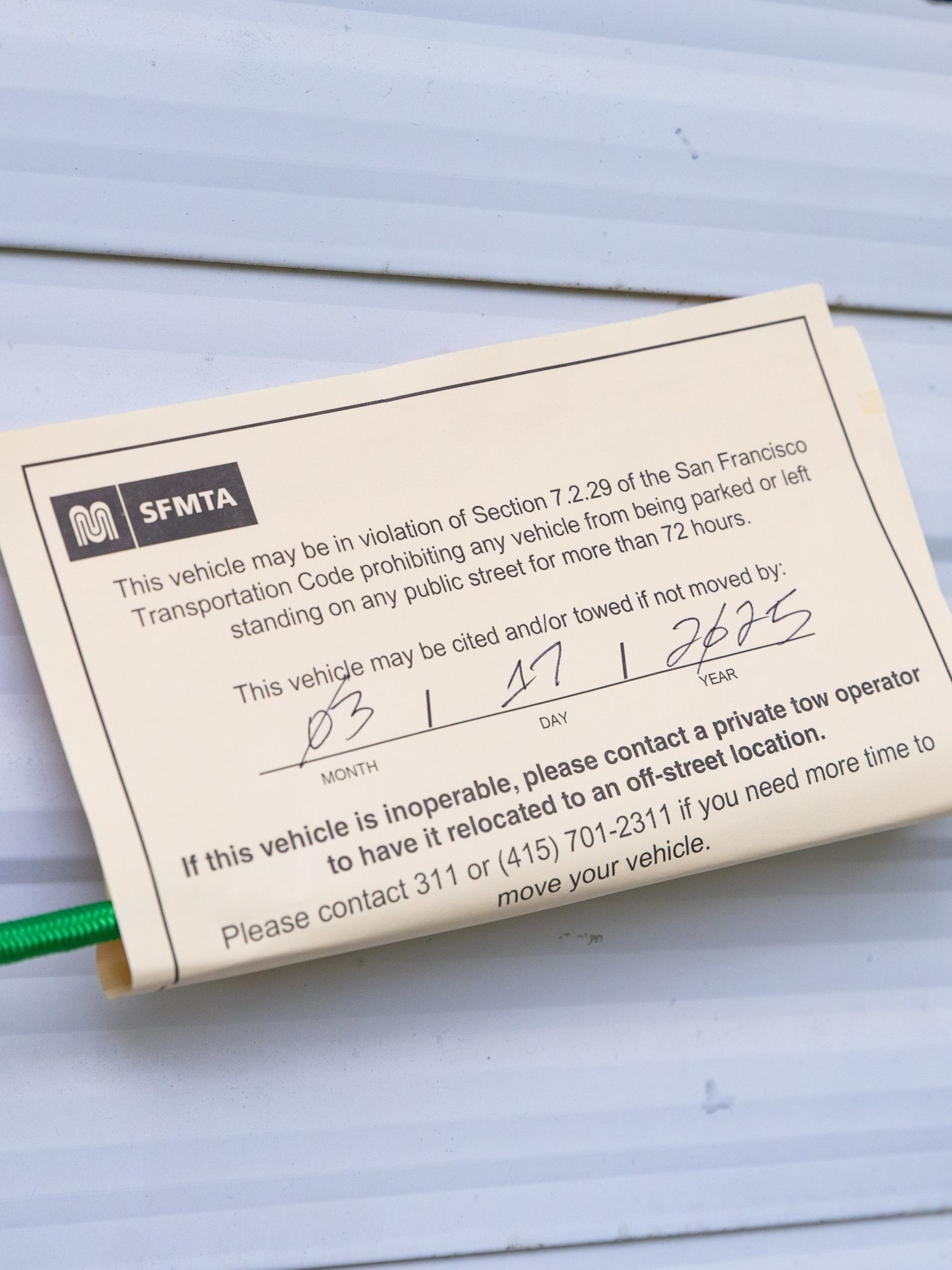

Several people living in the RVs said the city’s Homeless Outreach Team had promised them spaces at another parking site, Jerrold Commons. But when city workers moved the group on March 12, no social workers were on the scene — just police and tow trucks.

Officers informed homeless residents of their options: Leave, accept shelter, or have their vehicles towed.

“I was terrified. I’m too old and too sick to be towed,” said Mayon, who has cancer. “They never come through. It’s not the Department of Homelessness, it’s the Department of Gaslighting.”

The Department of Emergency Management said in a statement that none of the RV occupants on Gilman accepted shelter, but the city’s outreach team would “continue to work with the former guests to support their transition.” Of 42 people living at the triage site when it closed, the city moved 12 into housing and five to shelter.

After the sweep, the lineup of RVs scattered across the neighborhood. Those with working vehicles helped make last-minute repairs for less fortunate members of the group. One man, who was deaf and only gave the name Andrew, used a U-Haul to tow several vehicles to safety.

“I know it’s a lot, but we can’t leave anyone behind,” Mark Noti, an RV occupant, yelled to Andrew as they struggled to unlock the steering of one RV. “It’ll be a cold day in hell when I let them take something.”

By the end of the operation, at least three of the RVs had moved half a mile away. Another eight moved around the corner, next to a children’s park, where police immediately issued the occupants another five-day notice to move.

Some Bayview residents watched the reshuffling with heavy hearts.

“It could be me,” said Lajuan Bibbs, a lifelong resident. “I feel bad for them. They’ve got to live somewhere.”

Others looked on in disbelief.

“It’s stopping our kids from playing in the park,” said Gayle Hart, who lives across the street. “It’s ridiculous. No way in a community park in the Sunset or the Marina District would they have these RVs right here.”