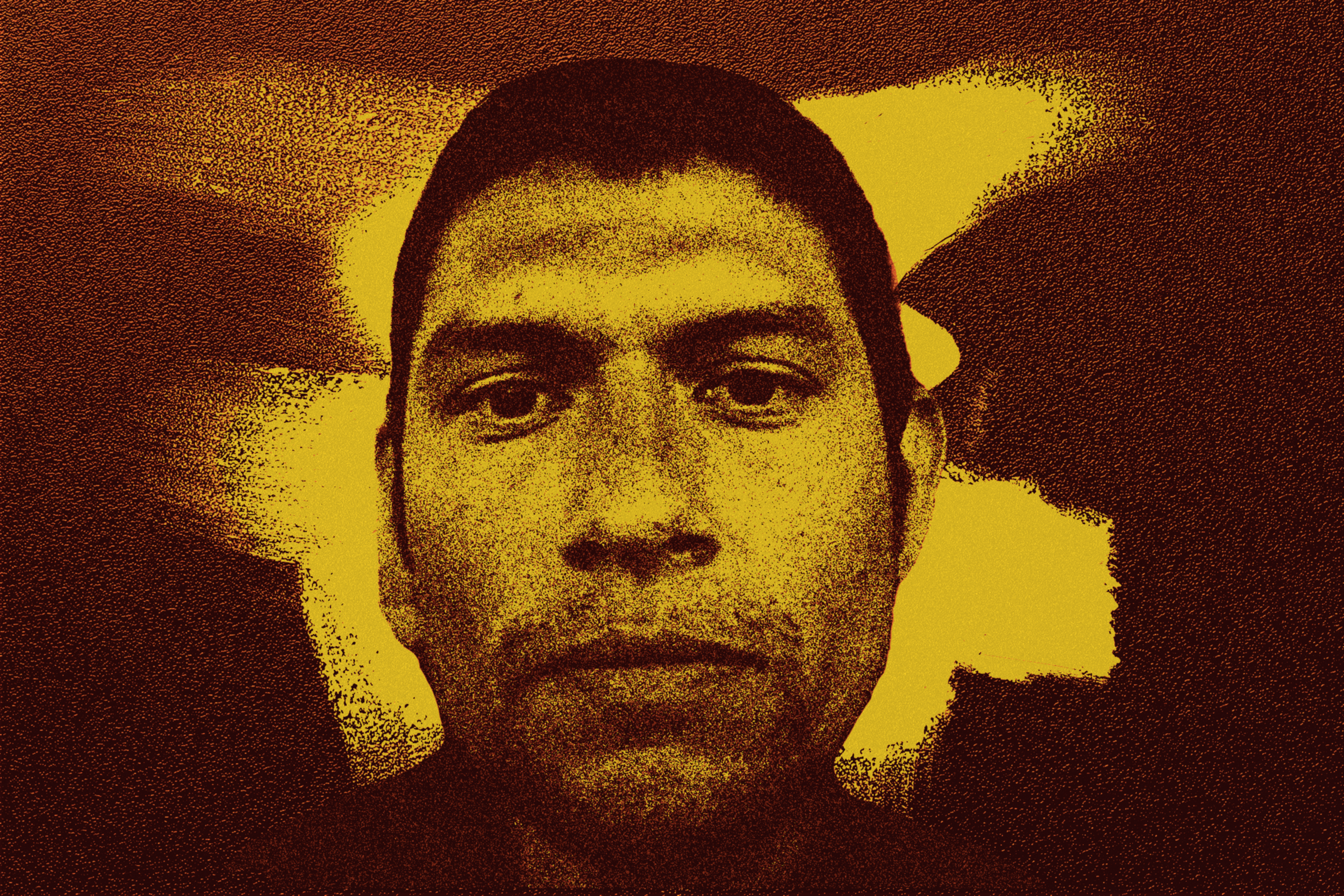

It was the restless summer of 2020, and Zero Triball was on a rampage.

The first warning came from the farmers market. Stall operators in the Castro complained to Supervisor Rafael Mandelman’s office that Triball, a homeless man, was harassing employees and customers.

Then it escalated. On June 8, a couple reported that Triball punched them as they walked through the Castro. Two days later, witnesses said he chased a business owner for a block and cornered him in a storefront. A week later, he allegedly vandalized a bar, The Detour.

By the end of the month, Triball had punched a man while his 2-year-old son looked on, sending him to the hospital with a broken jaw, according to court records and an interview with the victim.

These were not the first offenses Triball would allegedly perpetrate, nor were they the last.

Since 2020, he has threatened to burn down a community center and hogtie its owner, punched a man in the back of the head, broken another man’s nose, hit a person with a rock, and threatened to burn a tourist with a blowtorch (only to be beaten up by nudists), according to court records and reports compiled by Mandelman’s office.

These incidents are just a fraction of Triball’s publicly known crimes, and there are likely others that haven’t landed in court or the press, said Dave Burke, the Castro’s public safety liaison. Triball, accordingly, has served considerable time in county jail and rotated in and out of the city’s drug and mental health courts.

Victims say that isn’t enough.

To many in the Castro, 39-year-old Triball epitomizes a perpetual discontent with San Francisco institutions that they say have failed to protect them from violent repeat offenders. Some call it bad governance; others, Democratic malfeasance.

The reality, experts say, is that a Byzantine web of state and city infrastructure is unequipped to handle prolific offenders suffering from mental health and substance use disorders. Triball’s long-lost friends and family — some of whom did not know he was alive until contacted for this report — say a troubled childhood and young adult life led him to drug use and legal troubles.

But that may come as little solace to people who pass such offenders on the street every day.

“We give less rope to toddlers,” said Zack Karlsson, a resident who once found himself on the receiving end of a back-of-the-head sucker punch from Triball. “This guy is violent, and he hurts people and has hurt people repeatedly. Does somebody have to die before they do something? Even then, would they do something?”

‘He can still be saved’

In reporting this story, The Standard reviewed hundreds of pages of court records spanning two decades in three states. The documents offer a window into some of Triball’s darkest moments. But they don’t tell the full story of his life.

The way his friends and family put it, Triball is a good kid gone bad.

“He was the sweetest young man,” his sister Samantha Joe said through tears by phone from her Wyoming home. “We were so close. He’s a good man, he’s a good man. I hate that this is happening.”

Triball, who is currently in jail, was not available for an interview.

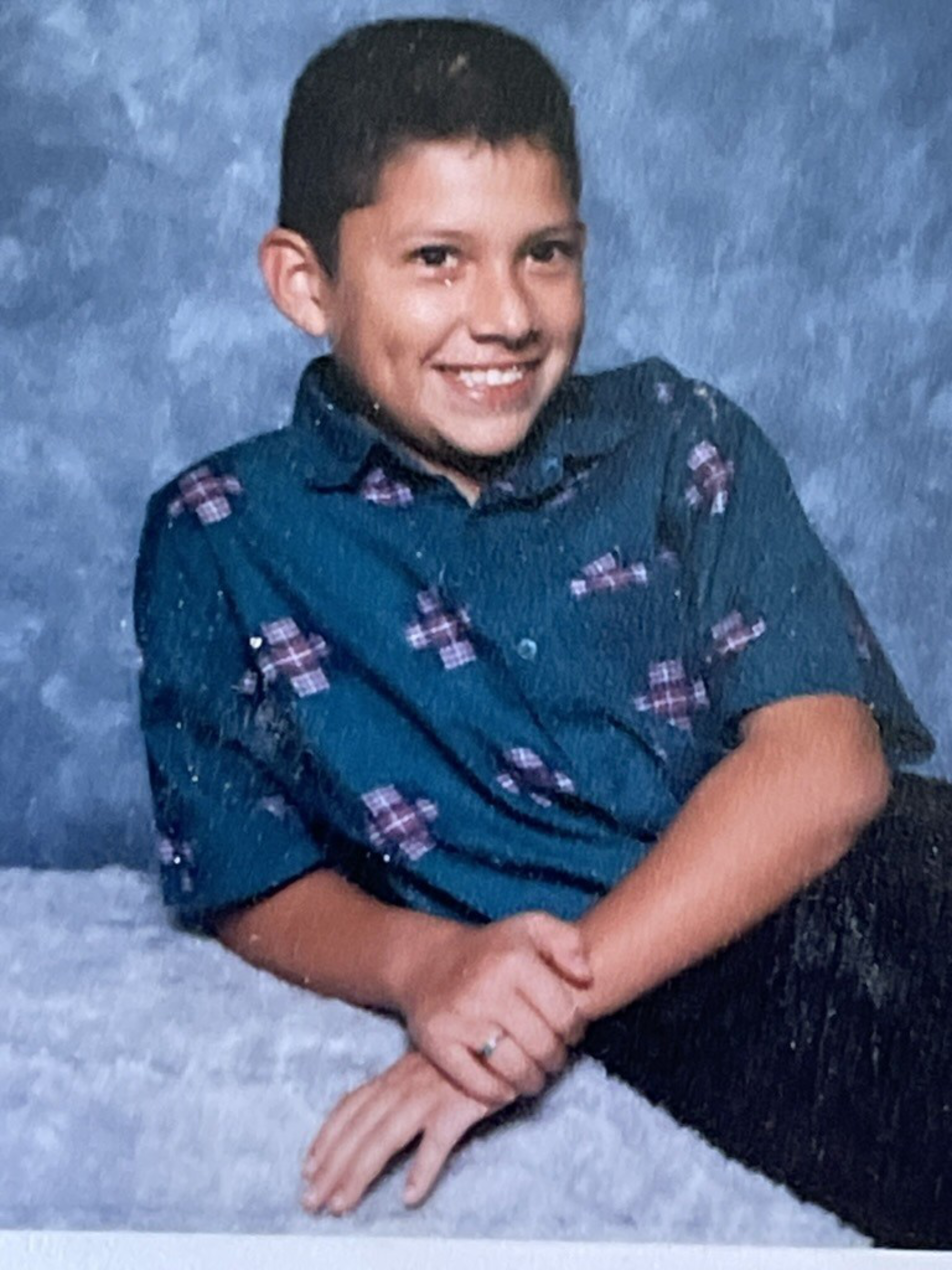

Born Kristo Armando Amaya Jr. on Jan. 4, 1986, Triball spent the first few years of his life in Oceanside. His father was a radio operator in the Marine Corps at Camp Pendleton, and his mother was a homemaker. They divorced when Triball was a toddler.

Joe, who’s 18 months older, said the siblings were raised largely by their maternal grandparents in Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska. Life at home was tough.

The siblings wore long sleeves to cover their bruises, she said, adding that Triball sported a scar on his forehead from when their mother’s boyfriend slammed him into a pool table. Their grandparents were “manipulative” and frequently reminded the kids that they “could’ve been in foster care,” Joe said.

But Triball, who didn’t change his legal name until age 28, got the worst of it, in Joe’s telling.

“He would do things that they considered effeminate — he would hold his hand a certain way — and they’d be like, ‘You’re not a fag, don’t put your hand that way, don’t be a little pansy,’” Joe said.

Their mother, PaulAnn Evans, who did not live with them at the time, denied that her children were ever abused, though she acknowledged that her parents were “super strict.” She said Triball earned the scar on his forehead in a pillow fight with five other children. The Standard was unable to reach Triball’s father.

Joe and her brother were close. When she got pregnant in high school, Triball rushed to defend her from anyone who gave her dirty looks. He walked her to class and relinquished his lunch to satisfy her pregnancy cravings.

When Triball came out as gay while studying at Chadron State College in Nebraska, his already frayed relationship with their grandparents snapped, Joe said. That night, he tried to take his own life.

“He had a lot of anger and a lot of hurt, and he didn’t know what to do with it,” Joe said. “He ran off. He didn’t feel like he belonged.”

After leaving Nebraska, Triball bounced around homes. At one point, he lived with his mother in New Mexico, where her husband got him a job delivering medical oxygen tanks to homes, she said.

He drank excessively and smoked weed in the home, despite her repeated pleas not to do so, Evans said. Still, she described their relationship as “pretty good.”

“Everybody was so nice to him,” she said. “There were so many helping hands out there. You just can’t make somebody want to be OK. It broke my heart when he left.”

Around 2005, Triball lived in California’s Lancaster area, according to a friend. It appears he stayed in the state until at least 2009, according to Nebraska court records filed by debt collectors. In YouTube videos (opens in new tab), Triball has suggested that he lived in San Francisco for around two years during this time.

After a stint in the Golden State, Triball went north to Eugene, Oregon, sometime before 2014. There, he lived in a peeling house with wooden planks over the upstairs windows and a weedy front yard. He legally changed his name to Zero Triball, a reference to how his grandmother said he was worth “zero,” according to a friend who lived with him at the time.

Then things turned for the worse.

A friend, who wanted to be identified only as Tuck for privacy reasons, said Triball was infatuated with a man who claimed to be a Buddhist monk descended from vast wealth. The boyfriend, whose name Tuck could not recall, insisted that the U.S. government would soon collapse — but that he and Triball could flee to safety in China.

The Standard was unable to locate the boyfriend; Triball has claimed in several YouTube videos that a lover, whom he referred to also as his Buddhist “teacher,” succumbed to cancer.

Tuck said he frequently saw Triball and the boyfriend drink excessively, but he was unaware of any hard drug use. Triball was prone to erratic outbursts but was rarely violent, Tuck said.

“He had his head on him back then,” he said. “He knew what lines he could cross and what lines he couldn’t cross.”

Then the legal troubles began. During an absurd spat with a next-door bakery in 2016, Triball wrote “NO FUCKING PARKING DIPSHIT” on a customer’s Honda Fit, according to Oregon court records. He was convicted of misdemeanor criminal mischief and sentenced to mandatory community service.

Cheryl Reinhart, owner of the Sweet Life Patisserie bakery, said Triball frequently berated and screamed at customers but never physically assaulted anybody.

By June 2018, Triball was back in San Francisco. But at some point while in Eugene, he “fell off the face of the Earth,” Joe said.

In fact, neither Joe nor Evans knew Triball was alive until they were contacted for this report. They were unaware of his exploits in San Francisco; local news outlets haven’t reported his birth name.

“I thought my brother was dead,” was the first thing Joe told The Standard, crying. “The fact that he’s alive means he can still be saved.”

9 cases, 3 convictions

“Saving” Triball — and preventing him from harming more people in the Castro — has not proved easy.

There are three broad tools the city has to rehabilitate offenders.

The first is the traditional judiciary. A judge can sentence convicted defendants to prison time, and, in certain circumstances, order them held in county jail before trial. Indeed, Mandelman, who is now president of the Board of Supervisors, has asked judges on three occasions to detain Triball before trial, arguing that he posed a “significant public safety threat.”

But the reality is that while county facilities offer rehabilitation programs, simply jailing a defendant may do little to address the substance use or mental health disorders that drive their violent actions once they’re back on the street.

Court records and sheriff’s logs show that Triball has spent at least 600 days in San Francisco County jail, but it’s impossible to pin down an exact timeline because of privacy laws.

Triball has been charged in nine cases over six years and convicted of three crimes in the city: All were felony assault charges for attacks in 2020, 2022, and 2024, records show. In the first two cases, a judge sentenced him to prison, but he never entered a state facility because of his time served in county jail. He was ordered to serve probation for his latest assault.

Triball’s other, more minor, charges were either dismissed as part of a deal that required him to plead guilty to the assaults or dismissed after completing a pretrial diversion program.

The second set of tools at the city’s disposal are alternative courts. These include so-called collaborative courts (opens in new tab) like Behavioral Health Court and Drug Court, as well as the state-created CARE Courts.

In these programs, judges seek to rehabilitate those with qualifying mental health or substance use disorders using an approach that’s less punitive than that of traditional courts.

Participants appear before judges to provide updates on employment, housing, and progress in their rehabilitation programs. People who graduate from collaborative courts typically avoid prison time.

Such programs are voluntary. Medical professionals cannot forcibly administer medication, which means participants have to want to get better for the programs to be successful, said Melanie Kushnir-Pappalardo, director of San Francisco’s collaborative justice programs.

“There is a lot of accountability that has to go with it,” she said.

Court records indicate that Triball has visited Drug Court and Behavioral Health Court multiple times; details of what occurred or what qualified him for the programs are unavailable due to privacy laws. Community members have reported seeing him smoking meth.

Triball’s public defender, Will Helvestine, declined a request for an interview. But in a statement, he wrote that “Zero is serious about treatment, and at a recent hearing, he spoke directly to the judge and said that he wanted to break out of the cycle of addiction.”

The third, and perhaps most draconian tool at the city’s disposal is conservatorship.

These programs, which are overseen by the city, allow physicians to forcibly administer treatment to conservatees. But they must meet a narrow set of circumstances.

A prolific criminal defendant driven by mental health and substance use disorders would most likely fit a specific type of conservatorship outlined by the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, said Amy Harrington, a Bay Area conservatorship attorney.

To qualify (opens in new tab), conservatees must have a mental health illness or “serious problem” with drugs or alcohol, be unable to care for their basic needs, and be unwilling to get help on their own. This leaves a gray area.

“It’s cumulative,” Harrington said. “It’s like, when have you crossed the line?”

The public conservator accepts referrals from hospitals and other designated facilities. Typically, these referrals stem from 5150s, temporary psychiatric holds that enable hospital staff to admit and treat patients involuntarily.

In 5150s involving drug use, the patient often regains sobriety by the end of the mandatory 72-hour hold, so hospital staff often can’t advocate for longer detention, Harrington said. Triball has been placed on at least three 5150 holds since 2020, according to Mandelman’s office.

And then there’s the bed problem.

Bay Area counties have a perennial shortage of space in treatment facilities. In November, the San Francisco Chronicle reported (opens in new tab) that some conservatees waiting for beds continued to rotate through the streets, emergency rooms, and jail — the very cycle the overburdened system is meant to stop.

It is unclear if Triball has ever been conserved or referred to such a program, but in March, a judge ordered the Department of Disability and Aging Services to “initiate an investigation into conservatorship.”

‘He’s unchecked’

Castro locals, exasperated by Triball, argue that he needs to be locked in mandatory treatment until medical professionals determine that he won’t hurt anybody else.

Anything short of that puts them in danger, they say.

“This is such a classic failure of the progressive attitude,” said Rory Burdick, the man whose jaw Triball broke in 2020. “It makes me hope that the Republicans take California. And I’m not even Republican.”

“He continues to be a menace in large part because he’s unchecked by the city representatives who are supposed to be keeping us safe,” said Karlsson, the man Triball reportedly sucker-punched in 2020. The DA at the time, Chesa Boudin, did not file charges.

Burdick and Karlsson both said they want to see Triball in mandatory treatment. Mandelman has advocated for a conservatorship. Even Triball’s mother and sister agree.

“He needs help, and I don’t think he’s going to get it on his own,” Joe said.

She pleaded with San Franciscans not to simply dismiss her brother as untreatable.

“I’m not forgiving him, and I’m not saying it’s an excuse,” Joe said. “But he’s got a lot of anger that he hasn’t learned how to take care of. He’s got mental issues that he hasn’t been given a chance to address. And people have always written him off.”

If you or someone you know may be struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can call or text “988” any time, day or night, to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or chat online (opens in new tab).

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with previously unavailable information from court documents. The documents showed that Triball had been convicted of three crimes, not two, as an earlier version of this story said. After publication, The Standard also learned that a judge recently ordered a conservatorship investigation.