East Bay real estate agent Andrea Chopp was working to close in on a potential five-figure payday when she heard the words people in her profession increasingly fear.

Chopp, who works for Redfin, was in talks with a couple who wanted to sell their Craftsman-style North Berkeley home, which she pegged at a sell-price above $1.5 million.

The pair had one reservation: An agent from a rival brokerage had told them about a private network of listings only viewable by its clients. They were intrigued by this “whisper network of exclusivity” and were worried about missing out, Chopp recalled.

Her heart dropped. Chopp attempted to explain that restricting the market of potential buyers could ultimately lower their home’s sale price, but the allure was too strong. She lost the sale.

The practice by brokerages of maintaining private for-sale listings that are only available to their clients is increasingly widespread — to the frustration of unaffiliated agents. Listings of so-called “hidden homes” (opens in new tab) aren’t publicly distributed through the multiple listing service (MLS) databases that populate entries on sites Zillow or Redfin, making them popular with celebrities, high-net-worth types, and others who put a premium on privacy.

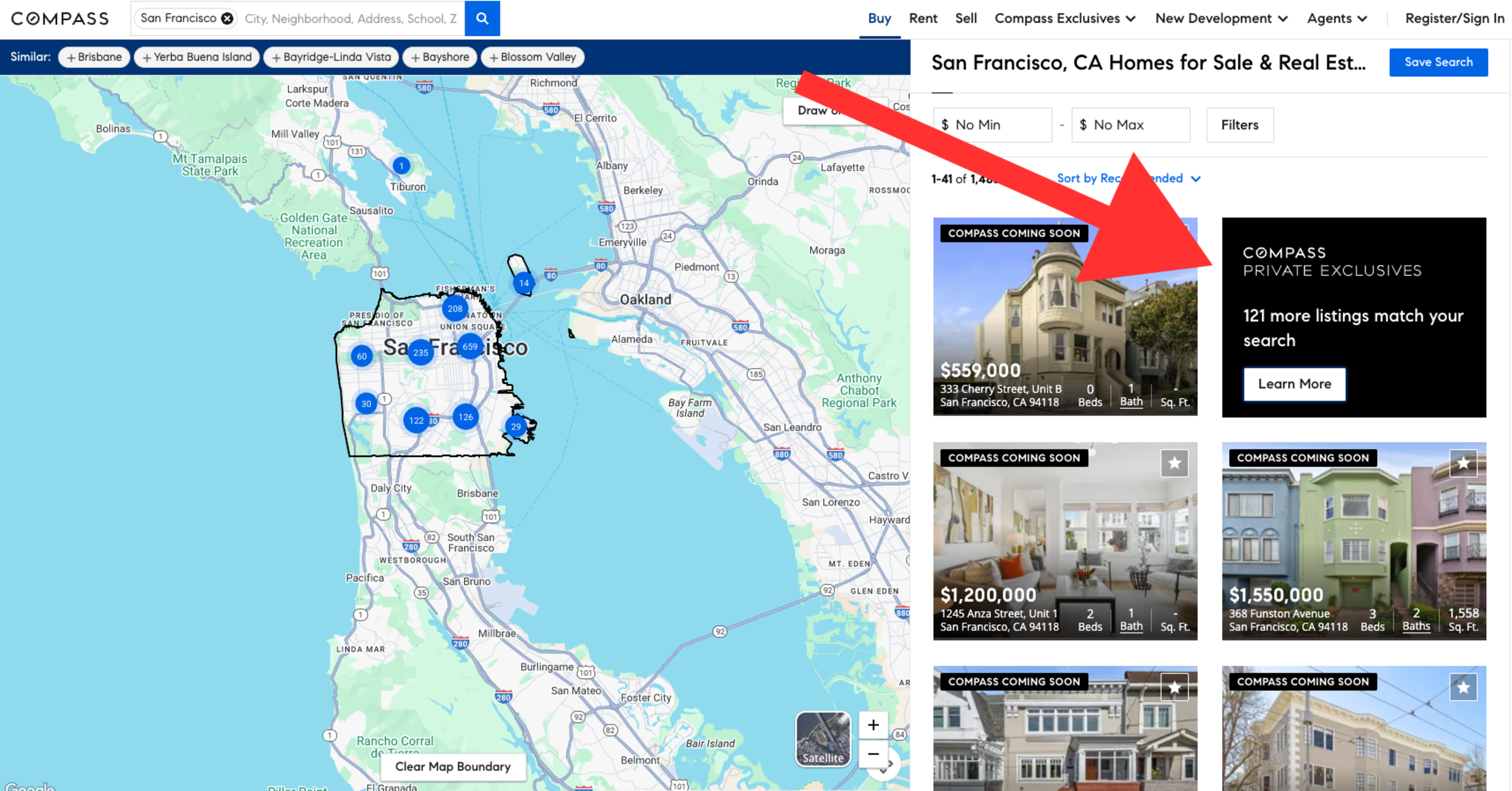

One of the country’s largest brokerages, Compass, has been particularly aggressive in pushing what it calls, evocatively, “private exclusives.” The pitch can be an effective one: Feel out the market behind the equivalent of a digital velvet rope; if you don’t find the right buyer, you can always go public later.

At least, that used to be the model. On April 10, the listings giant Zillow made a power move of its own, declaring that any home listed as a private exclusive would no longer appear on its platform, the biggest real estate site on the internet, by the end of this month.

For agents, who tend to have decidedly mixed feelings about Zillow, it was as though King Kong had emerged from the jungle to whomp Godzilla upside the head. Whom to root for: the platform squeezing them to pay fees for leads, or the mega-brokerage luring away their clients?

“On the one hand, I’m glad someone finally has the power to stand up to this practice,” said agent Jodi Nishimura (opens in new tab), who’s part of the Kai Real Estate group. “On the other hand, it’s Zillow, who for many years has been eating into agents’ hard-earned bread and butter.”

Rampant finger-pointing

While Compass isn’t the only brokerage with these exclusives, it currently advertises more than 100 in San Francisco on its website. The firm argues that a private network is the right choice for certain sellers, including anyone who doesn’t want to publicize details about their home or invite inside curious lookie-loos with little intention to buy.

The pitch can also be attractive to those looking to sell quickly, due to a death or divorce, or those who want to sell in, say, eight months, but would move out sooner for the right price. Compass touts data that shows that (opens in new tab) premarketed homes were associated with an average higher sale price last year.

For the brokerage, there’s also the competitive advantage it can hold over the heads of rivals — because having rarified listings is a selling point. Would-be buyers who want to get full access to all the potentially perfect Victorians or airy, modern lofts that Compass is selling in San Francisco would have to sign up to work with one of its agents. The network is billed as a “critical advantage in an inventory-constrained market.”

Critics call it a drag. Consumer advocates have described private listings as “terrible for buyers” (opens in new tab) and called upon the Department of Justice to investigate. Other brokerages have compared them to modern day redlining, or a predatory practice.

Detractors are also quick to point out that the practice allows Compass to double its commissions, since its agents are on both sides of the equation when a home is sold through a private listing. The sale of a $2 million home could bring a six-figure payout, for example.

Zillow has framed its decree (opens in new tab) as a fight for transparency and fairness. It cites its own data (opens in new tab) that says that privately listed homes sell for less — including by as much as $30,000 in California (opens in new tab).

The move sent shock waves through the industry, with some firms like Redfin quickly aligning (opens in new tab) with Zillow by also agreeing to ban these listings, while others accused (opens in new tab) the company of abusing its scale in the market. The CEO of Homes.com (opens in new tab) and CoStar group, Andy Florance, called it “a pure power play of epic proportions.”

“This isn’t about protecting consumers,” Florance wrote on LinkedIn (opens in new tab). “It’s about protecting Zillow’s ability to profit from listings by selling leads to competing agents.”

Nearly every party in the industry has been taking sides and bashing others for screwing people over.

“This is literally a few bad actors who are trying to move the industry back in time and make more money at the expense of buyers and sellers,” said Zillow executive Errol Samuelson. He argued that private listings mean “turning off the lights for a portion of the market, for buyers who no longer see everything.”

Ryan Schneider, CEO of Anywhere Real Estate Inc., which owns Coldwell Banker and Sotheby’s International Realty, said in the company’s first quarter earnings call (opens in new tab) that “we believe it is best for buyers to see all the inventory, and most critically, it helps sellers get the highest price for their home, full stop.”

Zillow’s announcement received blowback too.

Local real estate agent Kerri Naslund-Monday said the company’s stance is far from altruistic. “Zillow’s market is selling leads, so they’re afraid that they’re going to lose attention if they don’t have all the data,” she said.

Naslund-Monday, too, often markets homes for sale privately and questions how Zillow would even be able to find which listings to ban. “All’s fair in love and war,” she said. “If they’re going to be selling our very own listings back to us as leads, maybe they should have to do a little hunting every once in a while.”

Kevin Patsel, a Compass exec representing Northern California, said Zillow’s strategy is meant as a scare tactic intended to stop consumers from considering an option that might be good for them.

“What we’re fighting for is providing consumers with choice and not forcing them to comply with a company like Zillow that is setting rules based on [its] needs,” Patsel said. “Homeowners should have the right to choose how they market their homes, and Zillow shouldn’t take that right away.”

Smaller brokers surprised to be cheering on Zillow

While Nishimura doesn’t love Zillow, she still hopes its stance could stop the rise of the private exclusive strategy.

In her eyes, these listings “basically only benefit the brokerage” and their increasing use amounts to duping both sellers and buyers into limiting their options, especially in a place like the Bay Area with scarce inventory.

“It’s kind of predatory to capitalize on the desperation in the market so you can keep the business in-house,” she said. “To me, it’s so blatantly wrong, but there’s a lot of slick marketing around it.”

Lamisse Droubi (opens in new tab), who works with Generation Real Estate, described the strategy as “a basic grab for market share” that has contributed to the consolidation of the real estate market in San Francisco.

“If the goal is to monopolize information, I don’t see how that’s ever benefiting the consumer,” she said.

Redfin’s Chopp said that for buyers, the private listings market means being locked out of a potential purchase just because they didn’t want to lock arms early on with a particular brokerage.

“Instead of having a store that everybody can go to buy things, suddenly it’s like now there’s a Costco and a Sam’s Club that you have to be part of to even see what’s for sale,” Chopp said.

For sellers, her philosophy is simple: Unless there’s a reason for wanting more privacy, limiting the potential buyer pool just doesn’t make sense. “If you open your product up to sale to the largest possible audience, you’re going to get the most money.”