Mayor Daniel Lurie is finally showing his cards on how he plans to fund his ambitious homeless shelter goals — but it could be illegal and result in the city facing costly lawsuits.

Lurie is asking the Board of Supervisors to change the rules of Proposition C, a law passed by voters in 2018 to tax large corporations for homeless services, in a way that would shift $88 million intended for homeless families, youth, general housing, and prevention toward funding shelter. But this week, the city attorney’s office circulated a memo to supervisors warning of legal risks if the law is changed, The Standard has learned.

Jen Kwart, the city attorney’s spokesperson, declined to share the memo. But she said any changes to the legislation must align with the law’s original intent, as passed by voters.

The warning is weighing heavily on supervisors who are already wary of approving Lurie’s proposal, which requires a supermajority of eight votes to pass.

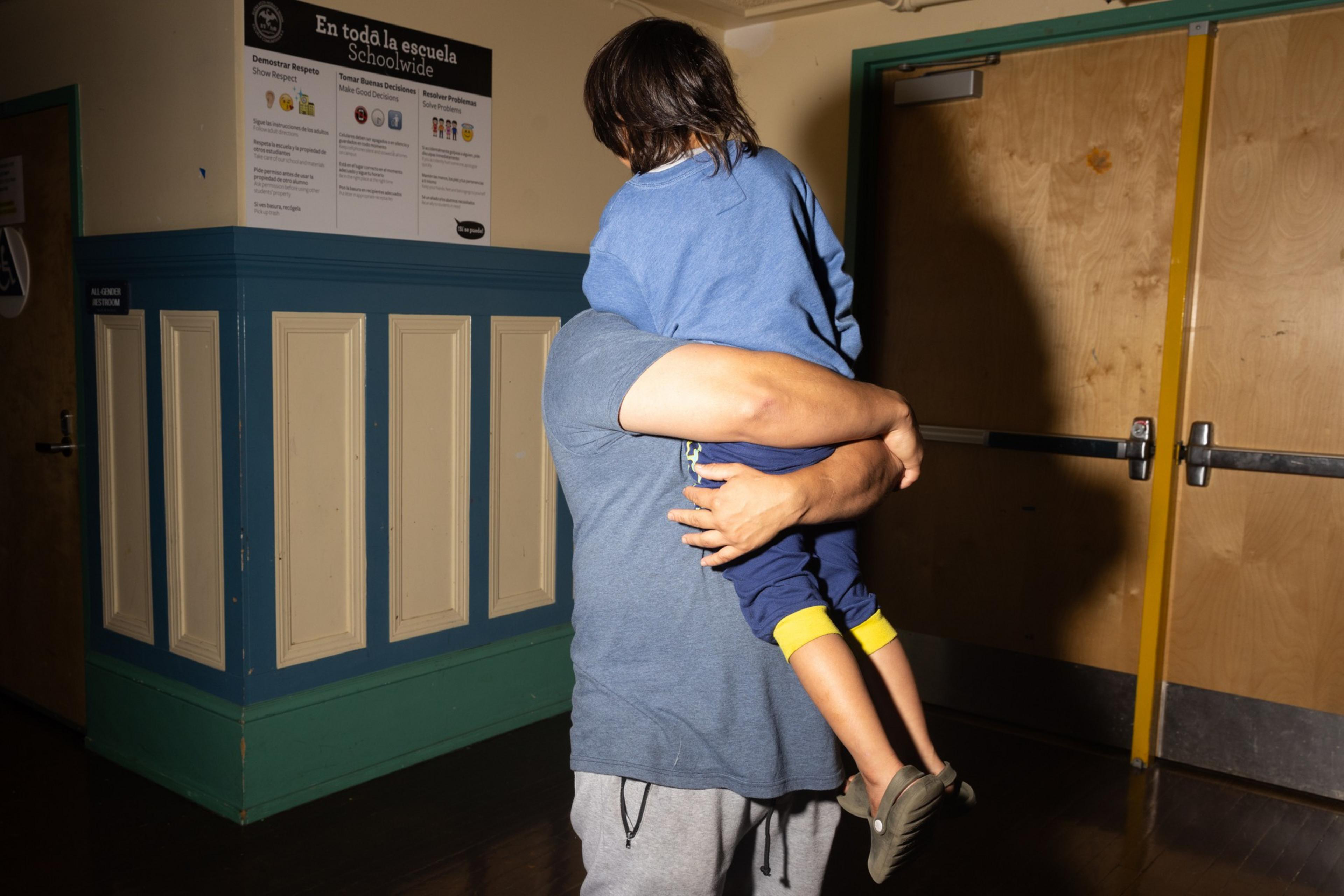

Supervisor Myrna Melgar said she understands the need for more shelter but is worried about pulling funds from homeless families and youth, who often aren’t as visible as single adults.

“I’m going to be very, very careful with the legal issues,” Melgar said. “The fact that they wrote a memo indicates there is a risk.”

As written, Prop. C requires the city to spend at least 25% of funds earned from the tax on mental health and 50% on housing, while up to 10% may be spent on shelter and 15% on prevention. As part of a plan to build 630 treatment and shelter beds at a cost of $121 million, Lurie is asking the supervisors to remove the regulations on $31.4 million for transitional-aged youth, $27.4 million for general housing, $19.8 million for family housing, and $9.8 million for prevention.

Christin Evans, an official proponent of the original law and homeless oversight commissioner, said she doesn’t believe these changes align with the law’s intent.

“Going back several mayors, there’s always been attempts to put more money into shelter and more money toward addressing visible homelessness, as opposed to actually going to the root causes of homelessness,” Evans said. “That’s why Prop. C was designed the way it was.”

Jennifer Friedenbach, director of the Coalition on Homelessness and an architect of Prop. C, said she would pursue legal action if Lurie’s proposal passes as is.

“It’s pretty clear to us that what the mayor is doing is illegal,” Friedenbach said. “What the mayor is proposing is we’re going to move money from one category to the other and wipe out the categories for three years and have a giant slush fund.”

After publication, Friedenbach asked to retract her statement threatening legal action, but maintained that the mayor’s proposal appears to be illegal.

The city last year counted a 45% increase in homeless families and a 19% increase in homeless youth, according to the most recent survey of the homeless population.

“Without these legally mandated set-asides, youth would be forgotten,” Marnie Regen, a director at Larkin Street Youth Services, said during a City Hall hearing Thursday. “Homeless youth are invisible. They hide in the shadows. This doesn’t mean they don’t exist.”

Kunal Modi, the mayor’s homelessness chief, contends that homeless families and youth stand to benefit from the city’s planned shelter expansion, arguing that the money had previously gone unspent.

“What we’re trying to do is use the unspent funds on the type of stabilization and treatment beds that can address the crisis on our streets,” Modi told The Standard. “Which will also benefit families and youth.”

Charles Lutvak, Lurie’s spokesperson, defended the proposal as in line with the original legislation.

“The intent of Prop C in 2018 was to fund solutions to homelessness. In 2025, families are sleeping on our streets and people are dying from overdose with nowhere to go, because the city does not have a bed for them to sleep in—all while millions of dollars raised through Prop C are sitting unspent,” Lutvak said. “San Francisco has a behavioral health and homelessness crisis today, and we cannot solve it without the interim housing and treatment support that will help those struggling on the street get onto the path to long-term stability.”

Sharky Laguana, a member of the homeless oversight commission, argued that the original law is outdated, and city officials should be liberated to spend the money on the current street crisis.

“If you’re trying to tell me that a group of people in 2018 know seven years later what is the best way to allocate those resources, I just find that incredibly difficult to believe,” Laguana said.

Supervisor Connie Chan, the board budget chair, aired concerns about the extent of the proposal during Thursday’s hearing. If the supervisors approve the motion, Lurie would have control over Prop. C funds for the next three years. If it is passed during this budget cycle, the mayor’s office would need only a simple majority of six votes to retain the changes in subsequent years.

As of Thursday, Chan said she was not ready to pass the ordinance without further explanation or amendments, signaling that Lurie may not have the votes needed for approval.

“We are confused about the plan. It has not been shown to us clearly,” Chan said. “And that’s a whole lot of money that we’re moving, and I am not getting sort of this definite answer that those families will be housed.”