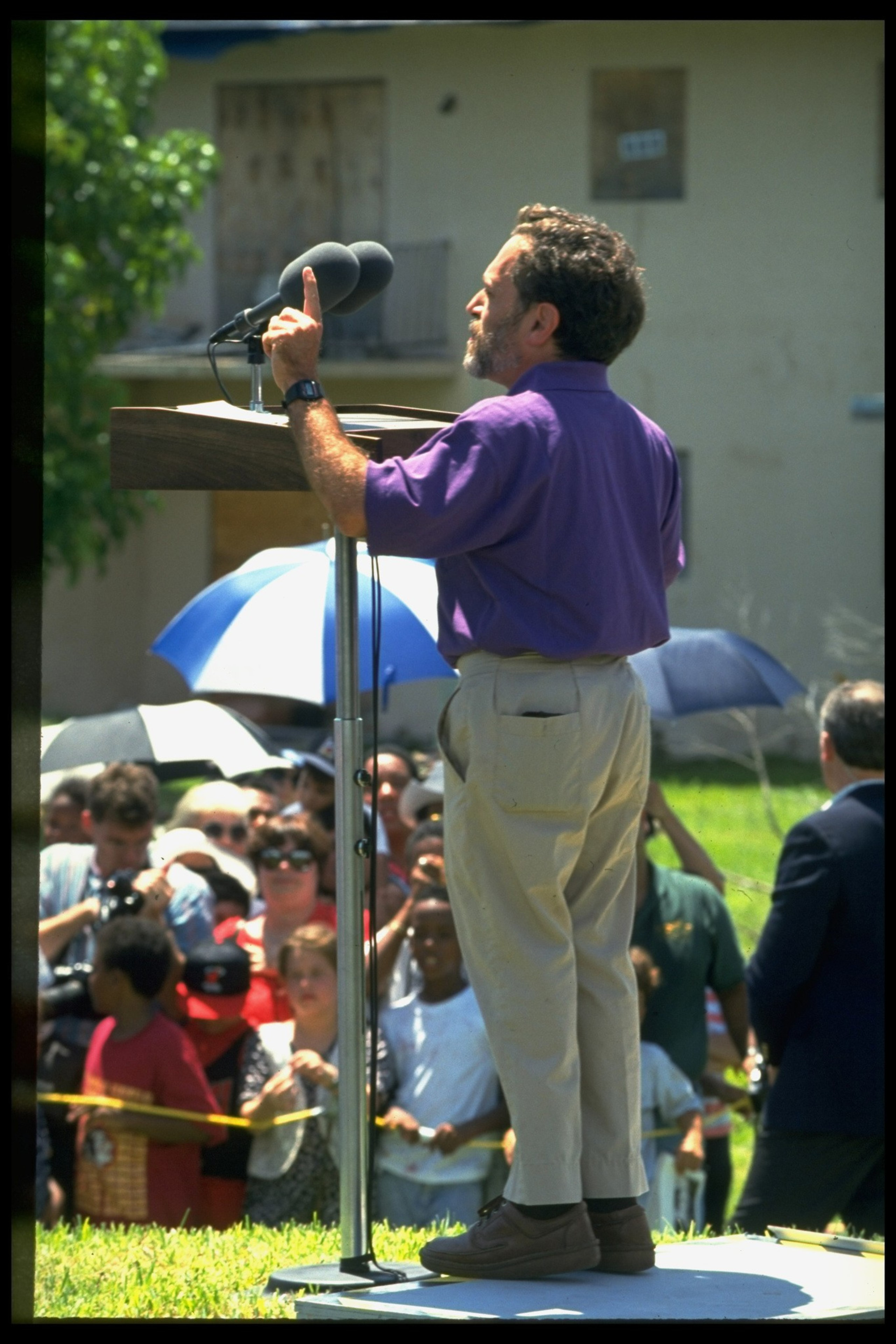

Robert Reich, the former labor secretary and longtime UC Berkeley professor, has spent a lifetime fighting for the working class. Now 79, he’s reaching a new generation, amassing millions of followers online (opens in new tab) with sharp critiques of corporate power and widening inequality.

This week, Reich releases (opens in new tab) “Coming Up Short,” a memoir that doubles as a national reckoning. The title is a nod to his height — just under 5 feet — but also to a country that, he argues, has fallen short of its ideals. He offers a blueprint for how to find its way back.

The Standard spoke with Reich in 2024 for an episode of “Life in Seven Songs,” our podcast that asks guests to share the songs that define their life. He reflected on the moments — and music — that shaped his politics: being bullied as a child, narrowly avoiding the Vietnam draft, and his love for Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5.”

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Students entering your lecture hall at Berkeley would hear “9 to 5” as they walked in.

Yes. It was my theme song, in a way. The course is about work. And I have been writing and worrying about the shrinkage of the middle class for many decades.

And you’re a fan of Dolly Parton. I read a tweet (opens in new tab) where you said you’re the same age, same height, same values. But she sings a little bit better.

She sings much better.

Where are you from?

I come from a little town 60 miles north of New York City called South Salem, which, when I first got there at the age of 9 months, was country. My parents worked six days a week in a little clothing store nearby. Looking back on it, the biggest gift they gave me was love. I was, and am, very short, a kind of a genetic condition. But instead of trying to increase my height, they smothered me with love. They told me I could do anything. They made me feel very confident

How did the community react when your parents arrived in South Salem?

They were met by a group of people from the community. My mother thought they were a welcoming party, but they were not. They told my father and mother that because we were Jewish, we were not welcome. My father, when he heard that they were bigoted, decided that he’d never leave. And so they stayed there for the next 25 years.

What were kindergarten and elementary school like for you?

A little bit fraught. When you’re as short as I was and am, the bullies really did see me as vulnerable. One day I went into the boys room, and second graders threatened to hold me upside down and put my head in the toilet. I ran screaming out. With my parents’ help and the help of the principal, I figured out that what I needed was an older boy to be my kind of protector. He was named Mickey. I forgot about Mickey until I learned that he, along with James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, had been tortured and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. When I heard that my own protector had been murdered by the real bullies of America, something changed in me. I began to understand that the definition of a good society was one that kept the bullies at bay.

You reached adulthood during a pivotal time. How did the events of the ’60s affect you?

I went to college starting in the fall of 1964. I was active in the anti-Vietnam movement junior and senior years. I went “Clean for Gene” — Gene McCarthy, who was the anti-war candidate. More and more of my friends were being drafted and sent to Vietnam. I had to do something.

Did you fear for yourself?

I thought I would be spared. If you were under 5 feet tall, you were not going to be drafted. But I wasn’t sure. I went to the Oakland Induction Center. The examining sergeant said, “You’re very short.” I said yes. He said, “You’re exactly what we need. We’re looking for tunnel rats.” But regulations are regulations. And I was 4-foot-11, and he could not accept me.

So you went to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar.

It was a great privilege. Right after Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were assassinated in 1968. And then Nixon is elected. What a horrible year. Then to go to Oxford — what an escape. I met Bill Clinton there. But at the same time, I was aware that it was fiction — an escape.

How did you meet Clinton?

We took the SS United States over there. It was a six-day journey. I got terribly seasick. There was a knock on my door, and there was a tall, gangly Southerner with chicken soup and crackers. He said, “I heard you weren’t feeling too well. I thought these might help.” I was surprised at his empathy, his compassion — or his political acumen, you might say. That was the beginning of a long friendship.

You felt a calling to return to the U.S. at some point.

I knew I had to. The question was, how was I going to take on the bullies of American society?

Did you have a sense at that point of whom you’d be fighting?

Time magazine did an article on the class of 1968, and I was one of the people they chose. The headline from my section was “The smallest big man on campus.” I engaged with bullies, really, beginning with the Vietnam War. I just felt that social justice required good people to be heard, to stand up, to prevent bullying.

What are you most proud of?

My years as secretary of labor and arguing before the Supreme Court stand out. The Family and Medical Leave Act was a major breakthrough. I’m also proud of what we did to close down sweatshops across America and raise the minimum wage. But I think teaching. I began in 1981, ended last year. I taught many thousands of students. Even if a small fraction go on to change the world for the better, I will have accomplished what I set out to.

How do you want to be remembered?

As a teacher.