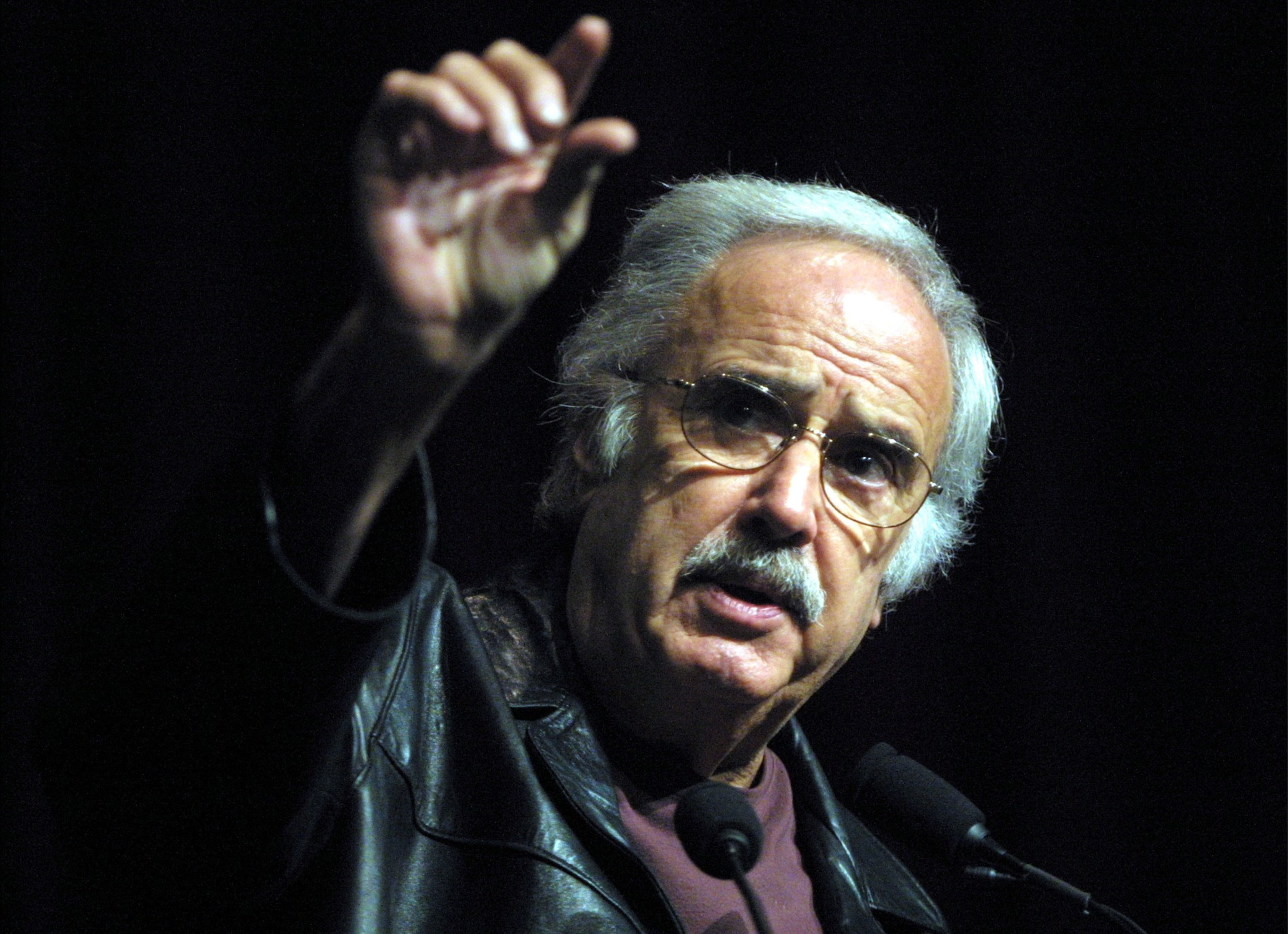

John Lowell Burton, the powerful Democratic politician who championed worker rights, environmental protection, and a host of progressive causes — and who used profanity almost as a form of punctuation — died Sunday at 92.

Burton served a combined 18 years in the California Assembly and eight more in the state Senate. He was a U.S. Congressman representing San Francisco County and, later, portions of Marin County for eight years and was chairman of the California Democratic Party in two terms totaling nearly a decade. Among his many accomplishments was reshaping and expanding the foster care system in California.

“There was no greater champion for the poor, the bullied, the disabled, and forgotten Californians than John Burton,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a statement. “He was a towering figure — a legendary force whose decades of service shaped our state and our politics for the better.”

It could be argued that Burton’s political legacy began in 1951 as he stood in line for Reserve Officers’ Training Corps at San Francisco State University. Students were grouped in alphabetical order, and beside Burton was another future Democratic titan who would become one of his closest friends: Willie Brown, the longtime California speaker and former mayor of San Francisco.

The two teamed up in a political juggernaut in California over the last half of the 20th century.

“That’s a good accusation against two college friends, law school friends, first elected friends, and two people who really love doing what we did,” Brown told The Standard on Sunday. “We both became leaders of various houses which we served: I in the assembly, and he in the Senate. And San Francisco has never had that kind of an operation, frankly.”

Brown added, “This may be the very first time we’ve been separated.”

“He and Willie Brown, for so many years, were almost a tag team working together,” said Larry Gerston, professor emeritus of political science at San Jose State University. “The period of the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s was pretty important for the reemergence of the Democratic Party in California, absolutely.”

Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi called Burton “a towering progressive warrior, who for half a century never pulled a punch in his dogged fight for a fairer future for our children.”

“All who knew John knew that behind his profanity-laden language was a profound progressive vision for how to make real the promise of America,” Pelosi added.

Born in 1932 in Cincinnati and raised in San Francisco, Burton earned a BA in social science in 1954 from SFSU and a Juris Doctor from the University of San Francisco School of Law. His brother, Phillip, entered politics first, becoming a prominent member of Congress who advocated for AIDS research. It was Phillip who urged John to join him in politics, which he did in 1974. He was re-elected to the four succeeding Congresses, until leaving the House in 1983. After a five-year break from elected office, during which he sought treatment for cocaine and alcohol abuse, he returned to the California State Assembly in 1988 and served until 1996.

In California, Burton’s legislative efforts focused on occupational safety, workers compensation, state worker retirement benefits, and student scholarships. He was also a staunch opponent of asset forfeiture laws, which allow law enforcement to seize the property of citizens suspected of illegal drug activity. He co-authored the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, which imposed economic sanctions on South Africa in response to its policies of racial segregation.

Burton’s profanity could be an attraction in itself. As chair of the California Democratic Party, he drew crowds at conventions where he was inevitably a featured speaker. Generally, an American Sign Language interpreter would be assigned to stand nearby to translate. Alicia Wang, who was vice chair of the party, recalled that during these speeches, “I’d be sitting on the stage and after a while I’d notice that everyone was looking at the signer. They’d all developed a sudden interest in ASL, because they were looking to see how you sign the F-word. Sometimes the signer would just blush and stop signing.”

Burton’s memoir (opens in new tab), “I Yell Because I Care,” was published just last week. His coauthor Andy Furillo told The Standard it was the honor of his lifetime to work with Burton, whom he described as more than a politician but a “man about town in San Francisco during the golden era between the Beats and the hippies.”

“John had great passion and compassion for working people, for poor people, for people who live in the SROs south of Market,” Furillo said. “They were his constituency. His entire political career was with them in mind.”

In a statement from Burton’s family, his grandson Juan remembered a phrase Burton had learned from his own father and which he repeated “so many times, we’d roll our eyes and repeat it along with him: ‘Never pass a blind man without putting a penny in his cup.’”

When he stepped down from state politics for good in 2017, Burton told reporters (opens in new tab): “You know, fighting for people and being able to win or improve their lives — for me makes all the bullshit worth it.”