Before the 1972 Transamerica Pyramid became an icon, it was the most-hated project in San Francisco.

Organizations lined up like chess pieces against it: San Francisco’s Planning Department, San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association (SPUR), the San Francisco Fire Department, the San Francisco Police Department, San Francisco Beautiful, the American Institute of Architects and numerous planning commissioners.

Designer William Pereira’s fame and charisma—he’s one of the few architects to appear on the cover of Time magazine—also wasn’t enough to convince people.

“Save our skyline from the Transamerica Pyramid,” exclaimed flyers protesting the construction of the triangular-shaped piece of San Francisco’s skyline. Allan Jacobs, then-planning director of San Francisco, described it as “an inhuman creation in an urban area that strives to be human and supremely livable.”

Half a century before there was “stop the steal,” there was “stop the shaft”—a slogan used by protestors who wore pyramid-shaped hats and handed out pyramid-shaped cookies (there was a pyramid-shaped cake, too).

The triangular-shaped goodies may have ended up popularizing the spire rather than lampooning it, since the building was a near-immediate success. Hailed as the world’s first modern pyramid, it was referred to as a symbol of San Francisco just a handful of years after it opened, one that was up there with cable cars and Coit Tower.

The 48-floor building cost $35 million to complete and includes a 212-foot unoccupied spire. The fifth floor is the largest, with 21,025 square feet (and the 48th is the smallest, with just 2,025 square feet). In 1987, more than 1,500 people worked in the building representing 50 different firms, including the Transamerica Corporation. The pyramid has a 9-foot foundation, which was the result of a continuous 24-hour concrete pour.

The building has 18 elevators, two of which reach the top floor, and boasts 3,678 windows—but it took less than two years to build, which seems like an unimaginable feat today.

The design was shrunk down from its original proposal, which was a towering 1,040 feet and almost within spitting distance of the 1,070 feet of today’s Salesforce Tower.

The Dutch insurance firm Aegon purchased the Transamerica Pyramid in 1999, and the Transamerican Corporation moved its headquarters to Maryland.

The Pyramid’s Transformation

Before the pyramid’s hate-love relationship with San Franciscans, it stoked controversy in another city—New York—where a similar design had been proposed as the headquarters for ABC.

“ABC, they’re a bunch of cowards,” said Michael Shvo, the developer who purchased the Transamerica Pyramid for a cool $650 million in 2020. “They said the design was too bold.”

In the ultimate embarrassment, San Francisco scored for itself a landmark, while ABC later ended up demolishing the building it constructed instead of the pyramid.

An exhibition at the Queens Museum titled “Never Built New York” included a model of Pereira’s original 1963 design and noted that the never-realized ABC headquarters was proposed for Columbus Avenue, across the street from Lincoln Center.

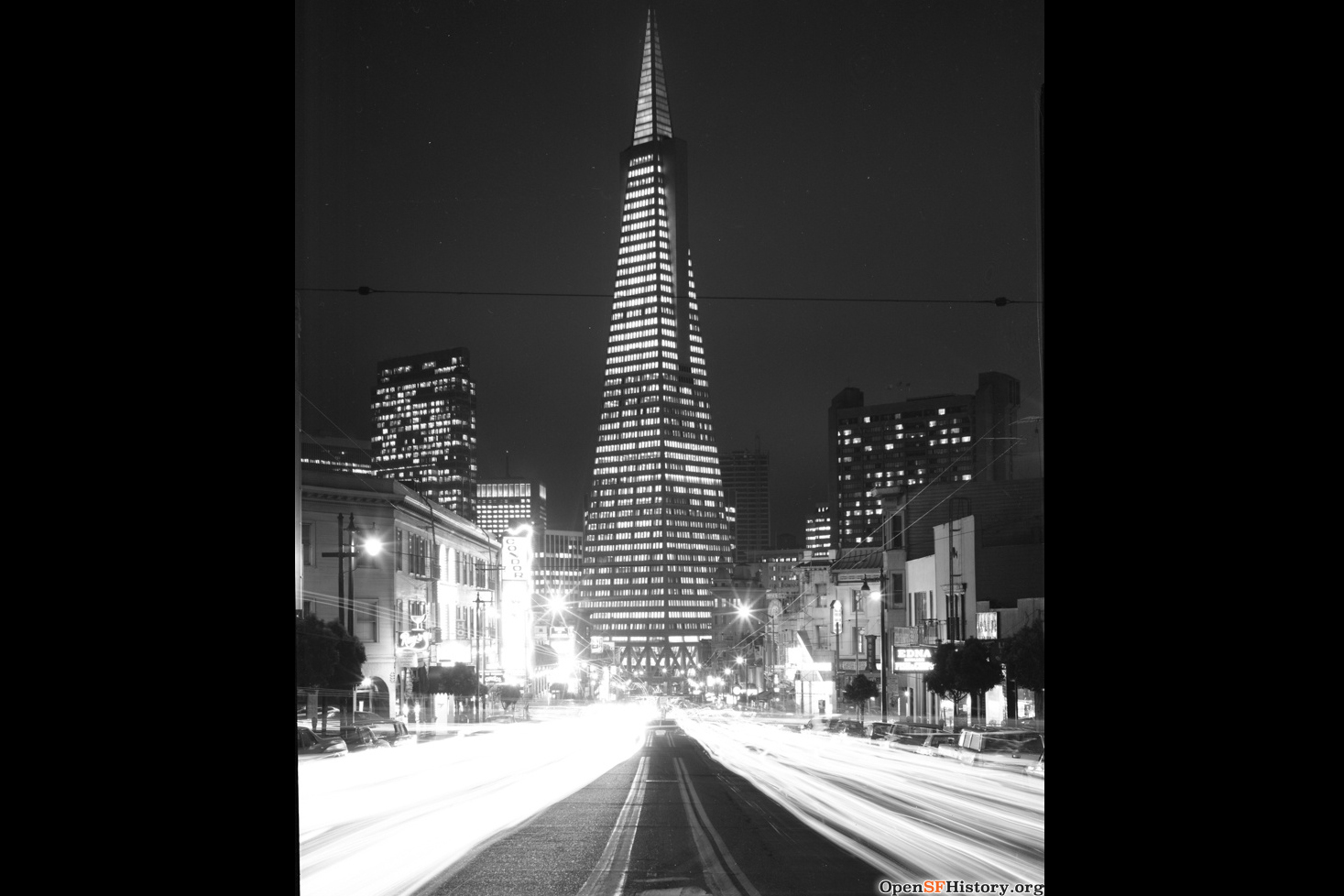

In one of history’s many coincidences, Pereira’s futurist building ended up adjacent to a different Columbus Avenue—San Francisco’s main thoroughfare through North Beach.

The pyramid rose a floor a week over Montgomery Street, opening in 1972 across the street from the flatiron building where the Transamerica Corporation had its roots. (A.P. Giannini’s multipronged financial empire eventually became both Transamerica and the Bank of America, and today houses a Church of Scientology.)

Even though the Transamerica Pyramid no longer serves as the corporate headquarters of its namesake, the insurance and investment company uses the building’s shape in its logo as a nod to its famed association.

San Franciscans surveyed today uniformly approve of the tower. “It’s iconic,” said Mila Shimko, who has been inside the tower on the 14th floor and remarked on the incredible views. Another drew a comparison with the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty—structures also hated before becoming beloved. At 853 feet, the Transamerica Pyramid was the tallest structure in San Francisco when it was built, a title it held for nearly five decades before the Salesforce Tower snatched it.

“It’s a landmark, and it’s recognized,” said Alicia Perez, who works as a sales and marketing manager for Giuliani Construction and Restoration. “If it was gone, people would notice something lacking.”

While the building is not currently open to the public, some 30 people come in every day requesting a tour, according to an attendant working the front desk. And elementary schoolchildren have been visiting the pyramid’s 36th floor as part of a citywide program.

“I remember my field trips as a kid,” said Russell Eisenman, the assistant general manager of the building. “Can you imagine coming to the pyramid on a school trip? What an incredible memory.”

Layers of History

The corporate emblem became a city landmark on what was already hallowed ground as the site of the Montgomery Block, an office and residential building that was a bohemian mecca. Writers like Jack London, Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain lived or worked there (the 1865 building was constructed on yet another layer of history, the Niantic sailing ship that became part of its foundation).

Nicknamed the “Monkey Block,” the Montgomery Block was the largest office building of its time—and the tallest building west of the Mississippi when it was constructed in 1853—and one of the few buildings in the area to survive the 1906 earthquake and fire thanks to its steel structure. Its offices had saunas, Dionysian baths and billiard rooms. It also had affordable housing, which made it possible for artists to live and work in the area.

Sun Yat-sen drafted the proclamation for the Republic of China within the walls of the Montgomery Block, and Robert Louis Stevenson chartered a yacht there for his voyage to the South Seas.

But most famed of all was the saloon, with its marble-tile floor, Wedgewood porcelain beer pumps and solid mahogany bar, where Duncan Nicol, inventor of San Francisco’s signature Pisco Punch, tended bar.

The Transamerica Corporation re-created the legendary Bank Exchange when it first opened with a saloon and restaurant that featured an exact replica of that mahogany bar.

Ralph J. Brady, a civic leader in the 1970s, recalled surveying the re-creation of the Montgomery Block saloon inside the newly opened Transamerica Pyramid.

“It was a challenging invitation, being asked to the Transamerica Pyramid to view plans for the re-creation of the Bank Exchange, one of San Francisco’s most famous early day saloons—the Buena Vista of the City’s golden age,” wrote Brady, who was still not convinced by the insurance company’s design.

“Making a pilgrimage to the pyramid to examine San Franciso history is like being hit in the face with a lemon pie and quipping, ‘It’s crazy, but I like lemon pie however it’s served up,’” Brady said.

Brady’s comments, alongside the love and admiration for the landmark today, show just how much things have changed.

Yet despite being such a visual and popular landmark, there’s currently no way for the public to access the tower. There used to be an observation deck on the building’s top floor, but it closed in the 1990s. The appropriately named Vertigo restaurant, an upscale eatery at the base of the pyramid, has also long since closed. And while Shvo has announced extensive plans for upgrades, many of them will be membership-based or available only for tenants.

Shvo does promise, however, a redwood-filled park at the pyramid’s base that will be open to the public. But we’re still keeping our fingers crossed for a revival of Duncan Nichol's famed saloon for a third round.