San Francisco, California may be almost 2,400 miles from Montgomery, Alabama, but soon, the two cities will be linked by a bond as strong as welded metal.

Over the last month, Alabama-based artist Michelle Browder has been working out of The Box Shop (opens in new tab), a studio space in Bayview-Hunters Point, on a monumental sculpture honoring three Black women—whose pain and suffering in the name of medical science—has largely been obscured by history until recent years (opens in new tab).

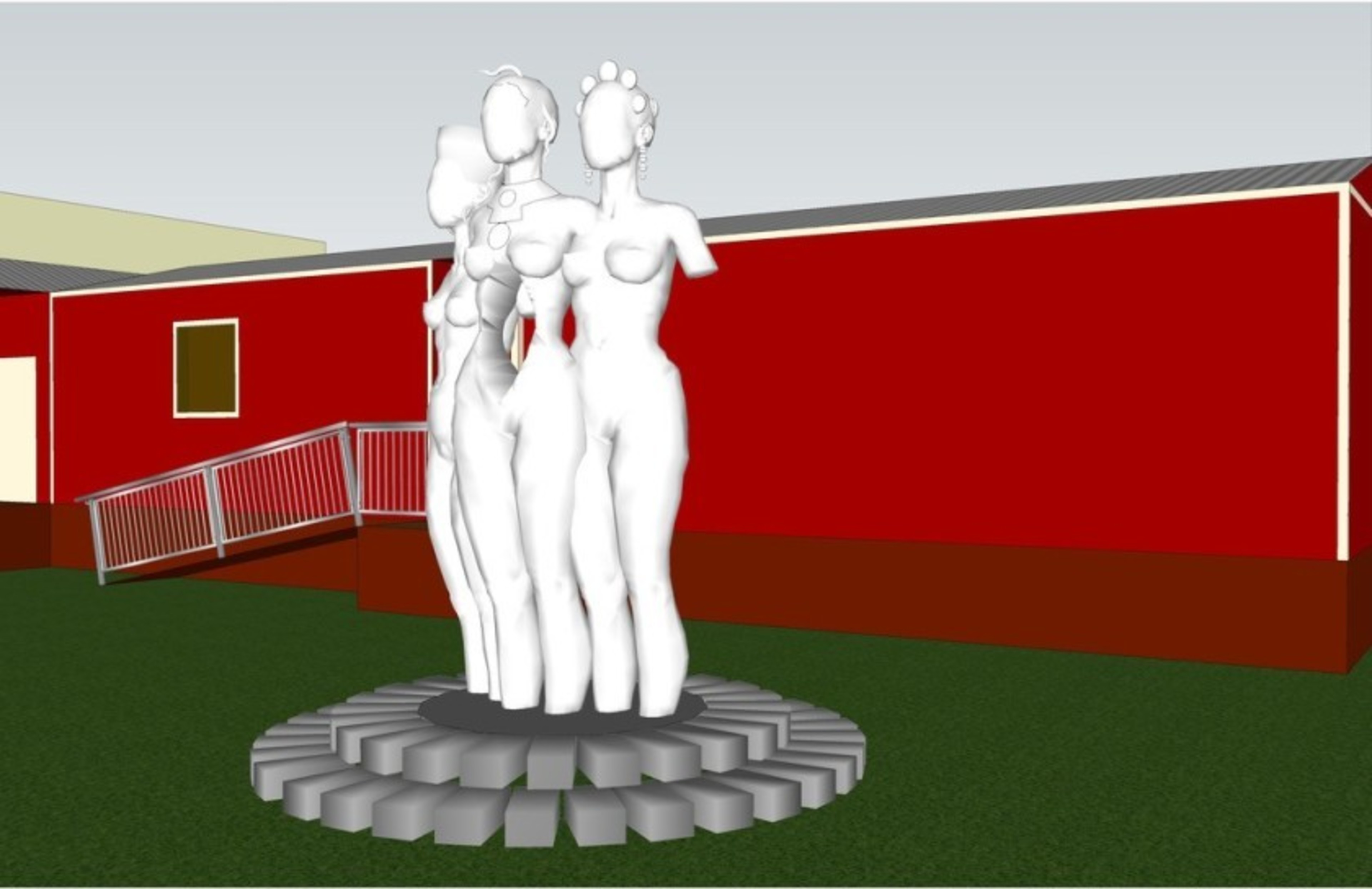

Each statue in the sculpture depicts one of three known women who underwent traumatic experimental procedures without anesthesia (opens in new tab) at the hands of 19th-century doctor J. Marion Sims (opens in new tab), the “father of modern gynecology.”

But these women are the “Mothers of Gynecology.”

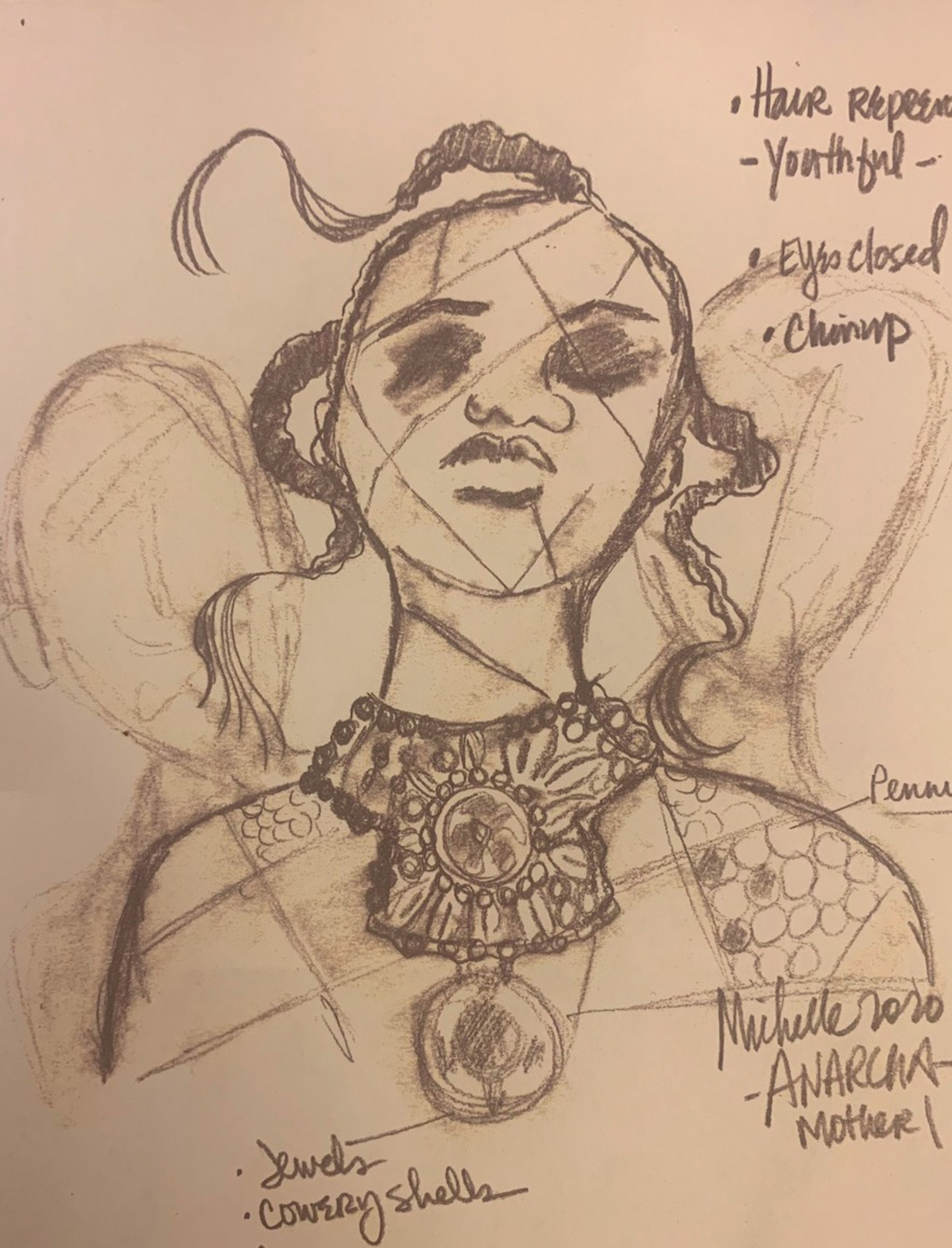

Anarcha stands 15 feet tall and “looks like a warrior,” says Browder. Her historical counterpart endured 30 operations before Sims perfected his method to repair a common and severe 19th-century childbirth complication that caused a rupture between the uterus and bladder (opens in new tab). Betsey is 9 feet tall and pregnant, a nod to the field of obstetrical medicine her body birthed through pain and suffering. And Lucy rises at six feet tall, a symbol of survival. The real-life Lucy fell critically ill after one of Sims’ surgeries. All three women were enslaved and likely could not consent (opens in new tab) to these procedures.

From sinuous spoons to cable wires, their sculptural representations are constructed with found and donated metal objects, and each statue wears a unique expression—“one of pain, one of honor and one of strength,” says Browder. Once fully assembled, they’ll stand on a platform of bricks emblazoned with the names of Black women such as Nina Simone, Eartha Kitt and Trayvon Martin’s mother, Sybrina Fulton.

The concept for a monument to the “Mothers of Gynecology” has been brewing in Browder’s mind for decades, ever since she first saw Robert Thom’s haunting portrait of Anarcha, Betsey and Lucy in Sims’ examination room (opens in new tab). But the idea to inscribe the names of impactful Black women at the foot of the sculpture as part of a fundraising effort (opens in new tab) came to the artist recently during her sojourn in San Francisco. Browder’s stay in the Bay Area is the third leg of a cross-country tour for the “The Mothers of Gynecology Monument” which will make stops in Austin, Dallas, Louisiana and Mississippi, before making its way to its permanent home in Montgomery—the same city where a controversial statue (opens in new tab) of Sims resides on the state capital’s grounds (opens in new tab).

By building this monument to the “Mothers of Gynecology,” and ultimately unveiling it just blocks away (opens in new tab) from where Sims conducted his experiments, Browder hopes to shift historical focus away from Sims to the real women, or “mothers,” he experimented upon.

“James Marion Sims … I think he’s had his due. He was not a saint,” says Browder. “Surely he knew that what he was doing was wrong because these were human beings. My end goal is to not only amplify their voices, but to bring humanity to these women—that they weren’t experimental subjects.”

A combination of serendipity and kismet brought Browder’s project to San Francisco. First, Browder connected with Bay Area local Kristin Eriko Posner (opens in new tab) through a historical tour that Browder gives in Montgomery. Posner then invited Browder to visit San Francisco sometime. When the two were touring Hayes Valley last year, Browder spotted San Francisco installation artist Dana Albany’s (opens in new tab) sculpture of an ancient female Buddha (opens in new tab), affectionately called “Tara” for short, on Patricia’s Green (opens in new tab).

Sophie Bearman for Here/Say

“I was in awe,” Browder remembers.

“She was just enthralled by ‘Tara’ and took a bunch of photos,” recalls Posner.

Then about a week later, Posner and her husband were at a dinner party and met someone who worked on the sculpture and was able to connect Browder to Albany. A year later, Browder is working with Albany, consulting artist Deborah Shedrick and a team of volunteer artists from all over the Bay Area and beyond to build the “Mothers of Gynecology.”

“I don’t like to say that the stars aligned, but destiny was calling us, and they called us to San Francisco,” says Browder.

The project has gained even more meaning as the statues have been assembled in Bayview-Hunters Point.

“To know that this is part of the old or one of the last Black communities in San Francisco by the bay, by the water… where these women are going to be erected, I think is phenomenal,” says Browder. “It just seems like this is the right place to do it.”

Some object donors have come from as far away as Los Angeles to contribute pieces to the sculpture. Volunteer artist Anthony Campanale traveled up from Southern California to donate a kit of surgical instruments, including forceps, clamps and umbilical cord-cutting scissors, that belonged to his mother-in-law, a nurse who worked on high-risk deliveries.

“When my wife found out about this project, she said she wanted to donate those pieces, that she thought it would be a good way to memorialize not just those three [women] but her mother as well,” Campanale told Here/Say.

Other volunteers, like Bernal Heights recycled glass artist Lauren Becker, have not only donated interesting objects but also their talents and expertise with particular materials.

“Basically I’m tracing the glass, making a little bezel or prong setting for it, and that’s going to get welded onto the piece,” says Becker, who also contributed a set of curvaceous candelabras that belonged to her grandparents. “I’m going to probably cry when I see them on these women’s thighs. They’re beautiful. They’ve got these nice sexy curves to them. They’re very feminine.”

This combination of found, donated, and “discarded” objects, as Browder also calls them, not only decorates the “Mothers” in magnificent sheaths of metal armor and bejeweled headdresses but also serves as a metaphor for the way that African Americans, especially Black women, have been treated throughout history.

“I wanted to tell a story about Black women and how even today we’re discarded,” says Browder, citing how Black women’s pain is regularly discounted by doctors (opens in new tab) and drawing a thematic line to gentrification. “When you talk about displacement, when you talk about being ‘discarded,’ Black people in San Francisco understand what that means with high rent,” Browder observes.

Gallery of 2 photos

the slideshow

Yet the abundant use of metal in the work also purposefully counteracts that narrative of oppression. For instance, a small bell once used to summon a Black maid has been repurposed as a decorative item on the hip of one statue.

“The metal tells a story in and of itself,” says Browder. “Like you can take a piece of metal, it looks dingy, it looks dirty. It looks like there’s no value in it. But once you clean it up, there’s value. There’s silver, there’s brass, there’s copper and beautiful colors, and I just thought that speaks to what these women were whereas white supremacy tells you that there’s no value in these women, but there is.”

Ultimately, Browder wants the “monument to draw from these disparate pieces, a spirit of camaraderie, community [and] conversation.”

While the final stop for the “Mothers of Gynecology” is Montgomery, where Browder plans to break ground on the monument (opens in new tab) on Mother’s Day, many pieces of San Francisco will travel with the sculpture on its cross-country journey, and Browder looks forward to maintaining the artistic bonds forged in the City By the Bay for this project.

“Everyone that donated a piece, whether it’s a little pair of scissors, glasses—people donated things that meant something to them,” says Browder. “So I’m hoping that people are happy to be a part of something like this and that they’re a part of the conversation. … You become part of the monument.”

Catch a last glimpse of the “Mothers of Gynecology” in San Francisco from 10 a.m. to noon on Sunday, April 4 (opens in new tab), at The Box Shop. To learn more about the monument, visit anarchalucybetsey.org (opens in new tab).

Video by Jesse Rogala.