Before Ida B. Wells, before Rosa Parks, there was San Francisco’s Mary Ellen Pleasant—a staunch abolitionist who refused to give up her seat on a San Francisco streetcar in 1866, a case that went all the way to the California Supreme Court.

She also was a fierce, sharp-witted businesswoman, owning everything from laundries to boarding houses, real estate to restaurants. At one point, she was worth more than $30 million by some estimates. One of the properties she owned, the Beltane Ranch, still operates today as a high-end retreat (opens in new tab) and another, the Geneva Cottage, served as a refuge (opens in new tab) in San Francisco’s Ingleside neighborhood.

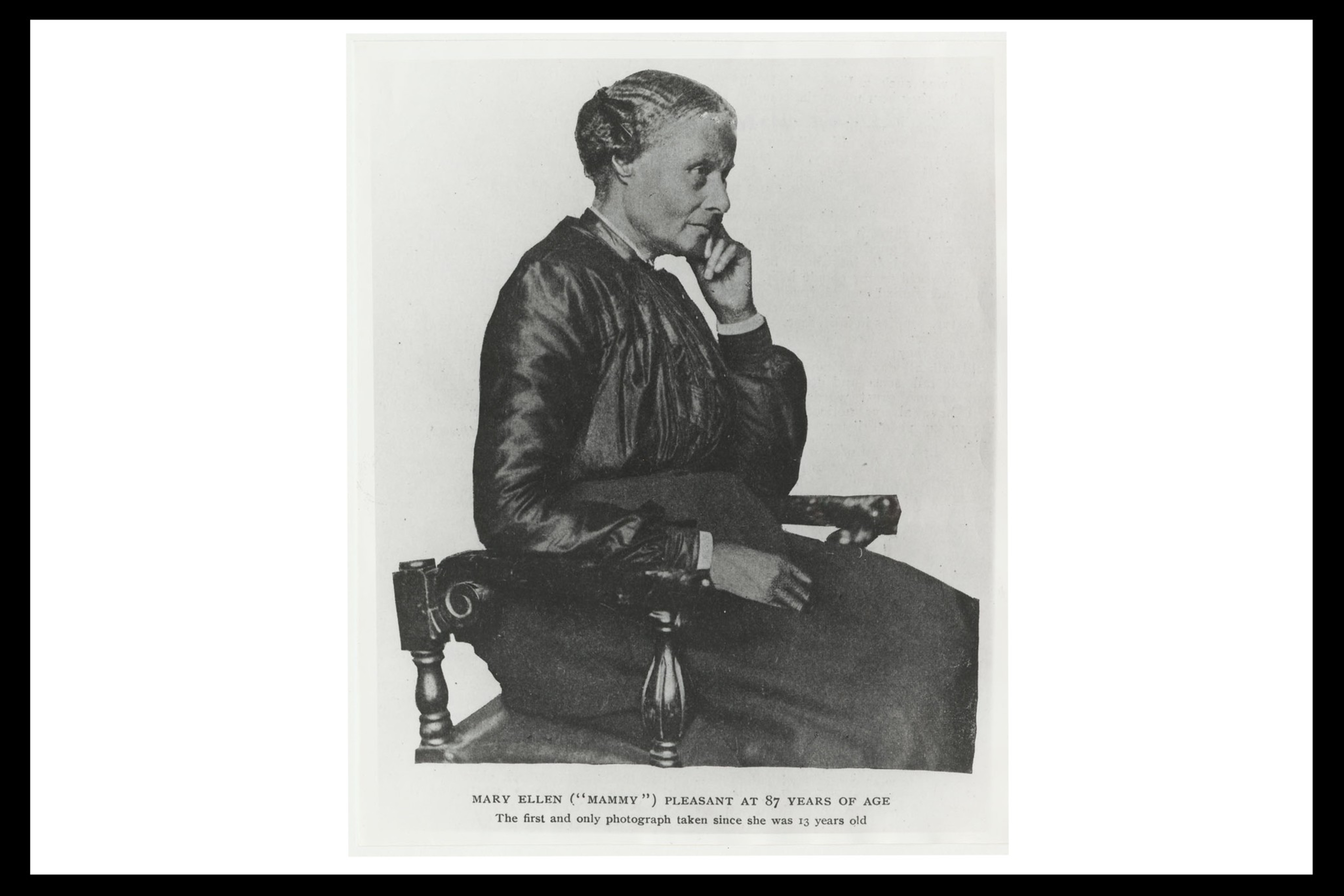

Yet Pleasant, who donated the equivalent of $1 million in today’s money to John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, has not become the household name that some of her fellow freedom fighters have. Her legacy is memorialized by a tiny, grassless patch—the smallest public park in all of San Francisco—that’s often used as a starting point for ghost tours during Halloween.

While African American organizations, activists and historians have never lost sight of her legacy, the fact remains that several features of her biography have conspired to keep her on the fringes.

One issue is that people associate the Underground Railroad with the East Coast, according to Lynn M. Hudson, author of The Making of “Mammy Pleasant”: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco.

“We don’t think of California as a place that had Black abolitionists,” Hudson said. “So that serves to erase her legacy as someone who worked on the Underground Railroad.”

Another problem is that many of Pleasant’s endeavors left little paper trail, and her three autobiographies contradict one another, all of which complicates telling her story.

But it was her participation in the William Sharon trial—what Hudson likens to the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky scandal of its day—that precipitated her demise and led to the salacious rumors that trailed her for the rest of her life.

Pleasant was the key witness in the trial of the U.S. senator, because she was the only one to see the marriage certificate that Sharon’s alleged wife, Sarah Althea Hill, said existed. After testifying on behalf of the white woman who was Sharon’s lover, Pleasant was labeled a baby killer and sorceress.

“That’s when she becomes a voodoo queen, when you see her in cartoons selling baskets of babies, when she’s putting spells on underwear,” Hudson said. “It’s all these stereotypes, many rooted in slavery.”

It makes one wonder why Pleasant would have the audacity to aid in the prosecution of a prominent white senator in a sensational case, with an enormous fortune to lose.

“She was committed to women who were getting totally screwed in every sense of the word by wealthy men in the city,” Hudson said. “It could have been that she felt like she was sticking up for yet another woman who was not getting her fair share of the deal she was promised.”

Originally from New Orleans, Pleasant moved to San Francisco from Nantucket in 1852 with her sights on the opportunities the Gold Rush city would provide. She gave shelter to the enslaved Archy Lee (opens in new tab)—another case that would go all the way to the California Supreme Court—and joined abolitionist committees, paving the way for the modern-day civil rights movement.

“What’s so fascinating is that Pleasant had her lawyer make the argument that she was harmed in mind and body when she was refused entry onto that streetcar,” Hudson said. “So she’s making this really interesting argument about how Jim Crow worked 100 years before Brown vs. Board—that segregation damages the self-esteem of Black children, what ends up being the most effective evidence.”

Pleasant later joined forces with banker Thomas Bell, combining their fortunes and households to live together in a sprawling mansion on Octavia Street. The arrangement gave good cover for Pleasant’s many business affairs, since she would not arouse suspicion by playing the role of domestic servant for the Bell family.

She and Bell lived together in the mansion on its manicured grounds—what is now the site for her memorial park—for nearly 20 years, until Bell’s untimely death from a fall over a stair rail, which the coroner’s office ruled an accident. Guides on San Francisco’s ghost tours will swear you can feel a chill in the air from Pleasant’s spirit, one that scares dogs and passersby.

But if anything of Pleasant’s ethereal spirit lives on, it’s in the trees she planted: the rustling eucalyptus on Octavia Street, the sway of the palms at Beltane Ranch.

Tales of voodoo spells and ghostly encounters are not the real story of Pleasant’s legacy—her absolutely fearless abolitionist work is.

“I’d rather be a corpse than a coward,” she writes in one of her memoirs.