Ebony Nolan expects trouble when she applies for a job.

One time, Nolan thought she was about to get hired as a bank teller. The interview went well, but after running a background check, the bank suddenly turned her down, she said. Another time, she had already started working shifts at a local sandwich shop before her conviction was flagged during a background check. She said she left that job soon after, too.

Nolan was convicted of a felony crime in 2007. Then 19 years old, she was sentenced to serve over 100 days in jail and three years of probation. But long after her incarceration ended, Nolan continues to face the fallout from her criminal conviction as it resurfaces during background checks.

That’s why she recently submitted a petition to get her record cleared through a process called expungement—a general term for the collection of legal processes Californians can pursue to make their criminal history less public.

For Nolan, expungement would have meant that her criminal case from 15 years ago was dismissed, allowing her to lawfully say that she has no conviction on her record when applying to most jobs or housing.

The trouble is, Nolan still owes about $700 in victim restitution, according to the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office. So prosecutors are opposing her expungement until she makes more payments to the court.

That’s left Nolan—who makes about $30,000 as the sole breadwinner for her two children—in limbo.

“I need to build something for them,” she said.

But without the expungement, that years-old conviction will continue to haunt her.

A Fresh Start

The Fresh Start Act (opens in new tab)—which is awaiting action on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk—would remove this financial barrier for Nolan and others seeking expungement. The proposed law, authored by state Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, would prevent courts from denying an expungement because the person owes an outstanding restitution debt.

If passed, people throughout California who owe court fees will gain an easier path to clearing their records.

Advocates for the Fresh Start Act say that tying expungement to people’s debts unfairly punishes the poorest defendants, and, in a twist of irony, prevents them from getting the jobs that could enable them to pay down the sum.

But defraying victim restitution fees from expungement will get rid of an important incentive to pay people harmed by crimes the financial amends they’re entitled to, said Kathy Storton, a retired prosecutor and member of the CA District Attorney’s Association Legislation Committee. Her organization opposes the bill, arguing that judges already have the discretion to grant expungements to defendants who owe outstanding fees.

If the governor vetoes Wiener’s bill—as he’s already done to another high-profile would-be law this legislative session—then here in SF, prosecutors in District Attorney Brooke Jenkins’s office will retain significant influence over who can get their record expunged. And local judges will continue to have the final say on the issue.

Debt to Society

Each year, tens of thousands of people are convicted of crimes across California, according to data from the Judicial Council of California (opens in new tab), the policymaking body of the state’s court system.

But even after they serve time behind bars and complete parole and probation, many are left with another debt to society: court fees. Some are fines, which can range from a few hundred dollars up to $10,000.

Courts also issue orders of restitution, which require convicts to pay money directly to a victim to cover costs that person incurred as a result of the crime, including the value of stolen property, medical treatment, wages lost due to an injury and more.

The median amount that California courts order defendants to pay to crime survivors is $10,000, Delaney Green, Clinical Supervisor at the UC Berkeley School of Law, found in an unpublished study of 15 counties. The study did not include San Francisco.

Currently, people convicted of crimes in the San Francisco Superior Court owe a combined outstanding balance of over $11.8 million to crime victims, according to data provided by the court. That figure includes fee accounts created in the past five years, so the grand total that San Franciscians owe in victim restitution is surely higher.

These restitution fees are a significant hurdle for San Franciscians seeking expungements, explained Vilaska Nguyen, a managing attorney in the Public Defender’s Office Specialty and Collaborative Unit.

“If there’s a red flag with victim’s restitution, generally the DAs are going to object,” he said.

The vast majority of expungement motions filed by the city’s Public Defender’s Office in recent years have been granted, according to data the agency shared with The Standard. For the past three years, about 95% of expungement motions were granted. But even with that high approval rate, dozens of people in 2020 and 2021 failed to get their records cleared—often because they still owed victim restitution, Nguyen said.

The majority of the cases during that time period arose during the tenure of former District Attorney Chesa Boudin. But in 2019, the year before the former public defender became the city’s top prosecutor, the number of granted expungements was significantly lower, coming in at 82%. That year, over 300 people were blocked from getting their cases expunged.

“Boudin’s administration was by far the most progressive and understanding compared to his predecessors,” San Francisco Deputy Public Defender Kelly Pretzer wrote in an email when asked to compare recent district attorneys’ records on expungement. “We are hopeful that DA Jenkins continues the practice of supporting people who have turned their lives around, particularly for those people who owe restitution on their cases.”

“The District Attorney’s Office follows the law, and objects in cases where probation conditions have not been met, including restitution requirements. The office has operated this way since DA Gascon’s tenure,” said Randy Quezada, spokesperson for the SF District Attorney’s Office. Quezada declined to comment further on the office’s expungement policies, or any of the data presented in this story.

So far, that data indicates that Jenkins’ administration is taking a tougher tack on expungement than her predecessor. There have been seven expungement cases where outstanding victim restitution was at issue since Mayor London Breed appointed her DA in early July.

Her office has opposed every expungement.

In one case, a man with a 2006 conviction for assault with a deadly weapon owes the court over $2,700 and has an annual income of under $10,000. His case was postponed so he could begin making “good faith payments” on his debt to the court before giving expungement a second shot.

Another man was convicted in 2010 of illegal possession of an assault weapon. He owes the court over $16,200 and earns over $112,000 annually. He also agreed to withdraw his case to refile after paying down more of the debt.

‘I’m a Good Person Again’

Celeste Saldaña was inspired by the resilient work of medical workers during Covid, so the mother of five decided last year to become a medical assistant. She juggled childcare and a graveyard shift at Amazon to put herself through school while also putting in work for a volunteer externship at an urgent care center. She was thrilled when the urgent care center offered her a job.

The excitement quickly subsided.

“When they did the background check,” she said, “my conviction came up.”

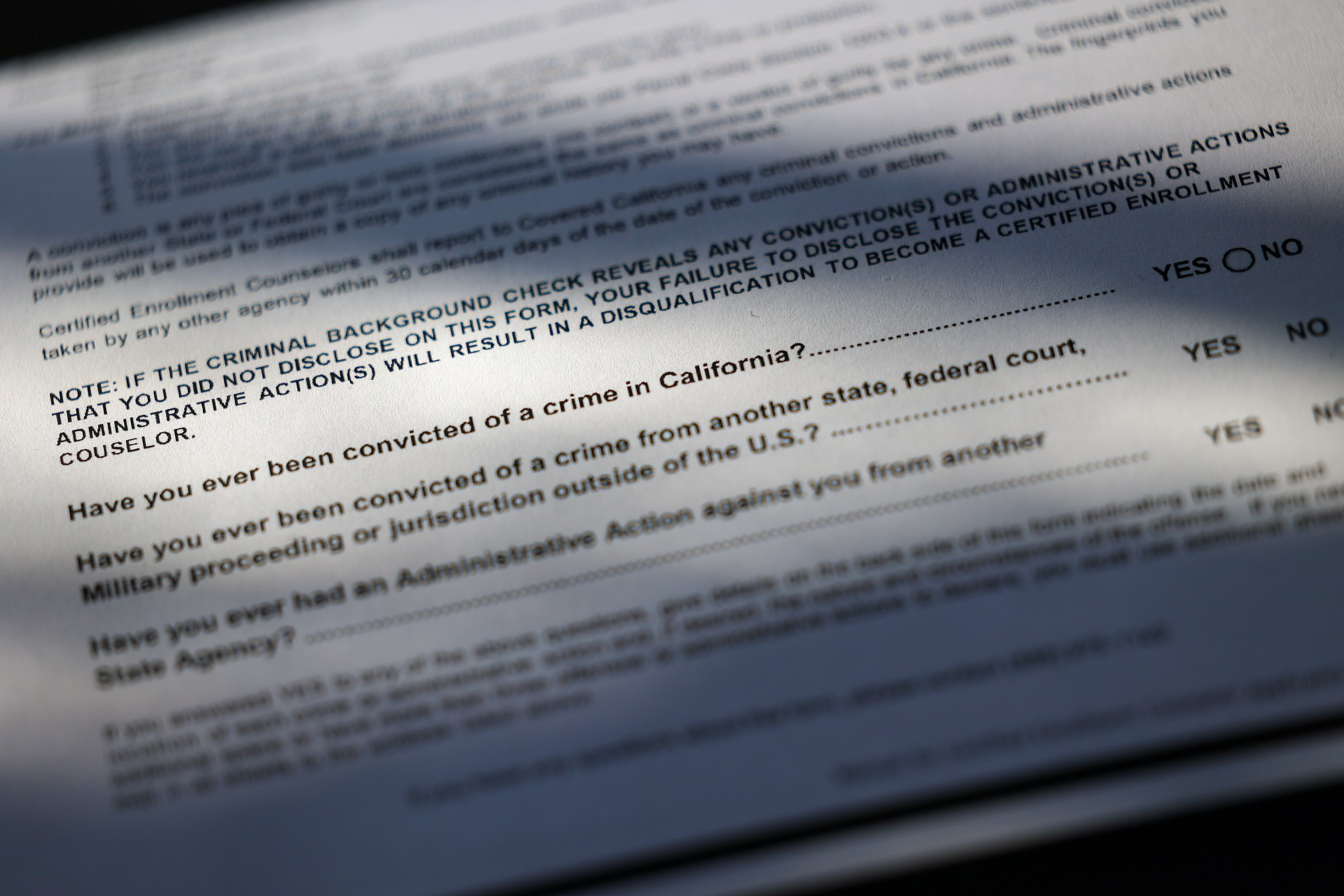

Saldaña, who was convicted of a crime in 2017, rushed to the courthouse that day to file the paperwork for an expungement. Reassured that the process was underway, the urgent care center brought her on as a medical assistant.

Earlier this month, a judge granted Saldaña—who owes over $4,000 in victim restitution—an expungement over the objection of the prosecutor, according to data from the Public Defender’s Office.

Saldaña says she felt elated.

“It shows that I’m a good person again,” she said. “I didn’t make the same error after error after error and never want to better myself.”

Instead of the person she used to be, the person who was always fighting, she said she’s now a medical assistant who translates for Spanish-speaking patients at her care center.

Ebony Nolan, meanwhile, was crushed earlier this summer when she learned she didn’t get her record expunged because of outstanding court fees. She currently hosts local pop-ups selling her signature “Bossy Wings” chicken and dreams of growing the passion project into a full-fledged company. But she fears her criminal conviction will hamper her every step of the way once she starts the process of launching a business.

“I don’t want to have this over my head,” Nolan said. “I know that I shouldn’t have made the mistake, but at the end of the day, I can’t take it back. The only thing I can do is move forward.”