Less than a year after joining the San Francisco Police Department in 2014, Rodger Ponce De Leon heard out of the blue from a teenager. They became Facebook friends, swapped nude photos and ultimately wound up in Ponce De Leon’s car, where he snorted cocaine, she smoked meth and they had sex.

This is the version of events SFPD heard from the teenager herself, Jasmine Abuslin, as a scandal unfolded around her in summer 2016. Abuslin alleged that she had sexual encounters with more than two dozen law enforcement officers from around the Bay Area, including at times when she was underage. She told SFPD that she had sex with Ponce De Leon on three occasions after her 18th birthday.

Ponce De Leon was stripped of his badge and his gun while awaiting discipline over the allegations, which are detailed here for the first time after The Standard won an extended legal battle to unseal court records.

But he wasn’t fired.

Instead SFPD assigned Ponce De Leon to a windowless room in Potrero Hill performing menial tasks with a morose group of officers who also have troubled pasts. He’s been there for more than six years earning a hefty salary that peaked in 2020 at nearly $240,000 for a combined total of about $1.2 million including benefits, according to city payroll records.

Together with 56 other officers sent by police brass to the windowless room since the beginning of 2016 and late 2022, Ponce De Leon and his colleagues have cost San Francisco an estimated $17 million, The Standard has found.

This kind of transfer, known as a “chief’s order,” is often but not always an indicator that an officer got into trouble, insiders say.

Ponce De Leon and his peers are stuck in a sort of purgatory that The Standard is exploring in a series of stories this week. SFPD spends millions paying them while asking for millions more to hire new recruits.

It’s here, at the Department Operations Center, where sworn officers manage a stolen and missing car database, send briefings to supervisors and field after-hours phone calls.

It’s much like the notorious “rubber rooms” of the New York City Department of Education, (opens in new tab) where reassigned employees get full pay and benefits that cost taxpayers fortunes.

Having a room like this means SFPD has somewhere to keep cops off patrol while figuring out whether to cut them loose or otherwise punish them.

But the practice also brings together embittered employees into a costly system that keeps officers accused of serious wrongdoing on the city payroll, while crushing morale of those accused of lesser misdeeds.

Inside the department, getting sent to the Operations Center is known as putting an officer “on ice.” Officers sent here face allegations ranging from the case against Ponce De Leon to a sergeant who nicknamed a recruit “Vegas” after she returned from a trip to Nevada.

Darius Jones, a former SFPD sergeant who spent 10 months at the Operations Center after he was accused of domestic violence, said the mood there is dispiriting.

He called it a cesspool of people who are “all wallowing.”

“Some people who come in are really bitter,” he said.

While Jones maintains his innocence, the chief did not believe him, and he was ultimately dismissed.

Officers enjoy extraordinary legal protections under state law that can let a case drag on for years and make imposing discipline difficult. SFPD needs a place to store officers while their cases play out.

Having an officer accused of misconduct out on the street means they could stumble upon evidence that requires them to take the witness stand. Their past conduct could tarnish such a case since defendants are entitled to all evidence that might prove their innocence.

“The police department, then, has to find jobs where that officer will never have to show up in court as a witness,” said Jonathan Abel, associate professor of law at UC Hastings Law School.

Even though this can be expensive—Ponce De Leon’s $240,000 in one year including benefits is unusually high for a clerk—police brass sometimes have few options for keeping officers away from the public and off the witness stand, Abel added.

“So they have to put them in some place where they can’t harm any cases,” he said.

Ponce De Leon’s peers over the years included a sergeant implicated in SFPD’s first racist texting scandal (opens in new tab), an officer who made false statements in federal court (opens in new tab) and a cop who shot at another driver while off-duty (opens in new tab). On average, these officers spent a year and a half at the unit before returning to patrol or severing ties with SFPD. Their total time served at the Operations Center amounts to about 33,000 days—or 90 years. Twenty of them ultimately left the department by termination or for other reasons.

The Standard combined the time these 57 officers spent at the unit with city salary data to reveal the estimated $17 million price tag.

Other cities have their own versions of a police rubber room.

In Los Angeles, police over the decades have been said to give officers “freeway therapy,” or send them to undesirable assignments as far away from their homes as possible.

Elsewhere, Abel said, it “can be sending memos, or writing emails internally. Other places, they will have an officer transcribing wiretaps or surveillance.”

San Francisco’s practice of stashing officers in a unit is no secret, according to retired Oakland police officer Mike Leonesio.

“It’s been well-known in law enforcement for decades,” said Leonesio, who currently works as a use-of-force consultant. “For whatever reason, they put them there, and they just spend the whole rest of their career there.”

In response to detailed questions and a request to interview Chief Bill Scott, SFPD spokesperson Sgt. Adam Lobsinger responded with an email rejecting the characterization of the Operations Center as a rubber room.

“We vehemently disagree that any of the units within the department are considered ‘rubber rooms,’” Lobsinger wrote. “That term is derogatory to the officers who sworn to serve and protect this city. Each assignment brings value to the department, and the officer’s unique perspective adds value to the assignment, including anyone assigned to the [Operations Center].

“It is inflammatory to consider any officer of this department is assigned to a rubber room,” he added.

That said, Lobsinger acknowledged that most duties at the Operations Center “can (and are) performed by both civilian and sworn staff.”

He said SFPD accounts for an officer’s skills and the needs of the department when transferring someone to the unit.

“Officers can be sent to the [Operations Center] for a variety of reasons that have nothing to do with discipline,” Lobsinger said.

Not explained in the SFPD statement is why, then, so many officers at the Operations Center have checkered pasts.

Contacted multiple times by The Standard, Ponce De Leon did not provide comment. One of his attorneys declined to provide a statement on his behalf. Attempts to reach Abuslin, including through her family and attorneys, were unsuccessful. The police union did not respond to multiple requests for comment on SFPD keeping officers on ice indefinitely.

An Unlikely Match

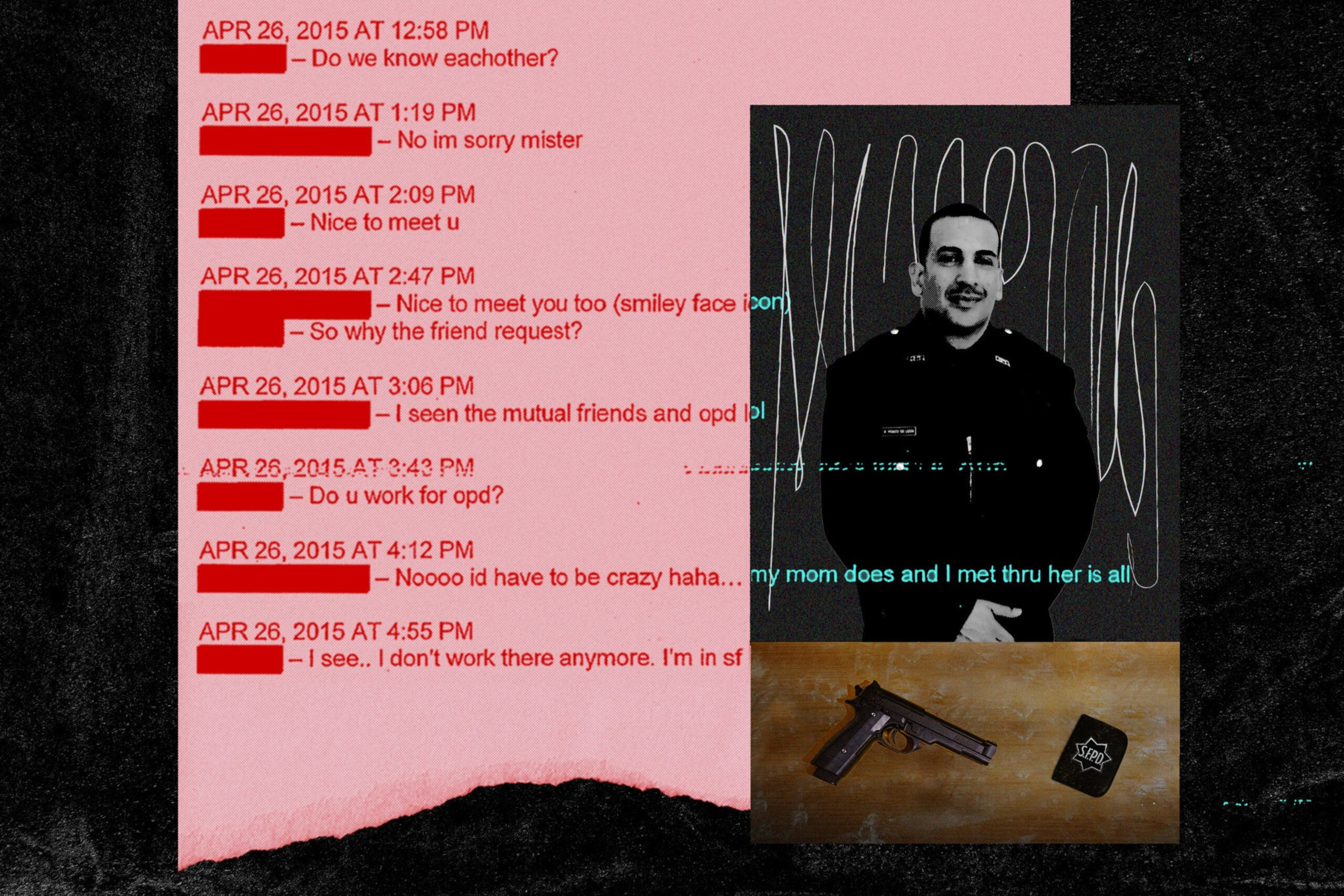

Ponce De Leon and Abuslin first met over Facebook on April 26, 2015. It wasn’t a natural fit.

Ponce De Leon was married, according to his Facebook page. Just six months had passed since he left the Oakland Police Department to join SFPD.

Abuslin, at 17, was a sexually exploited child. She contacted a large number of cops on Facebook—some of whom met her for sex before her 18th birthday.

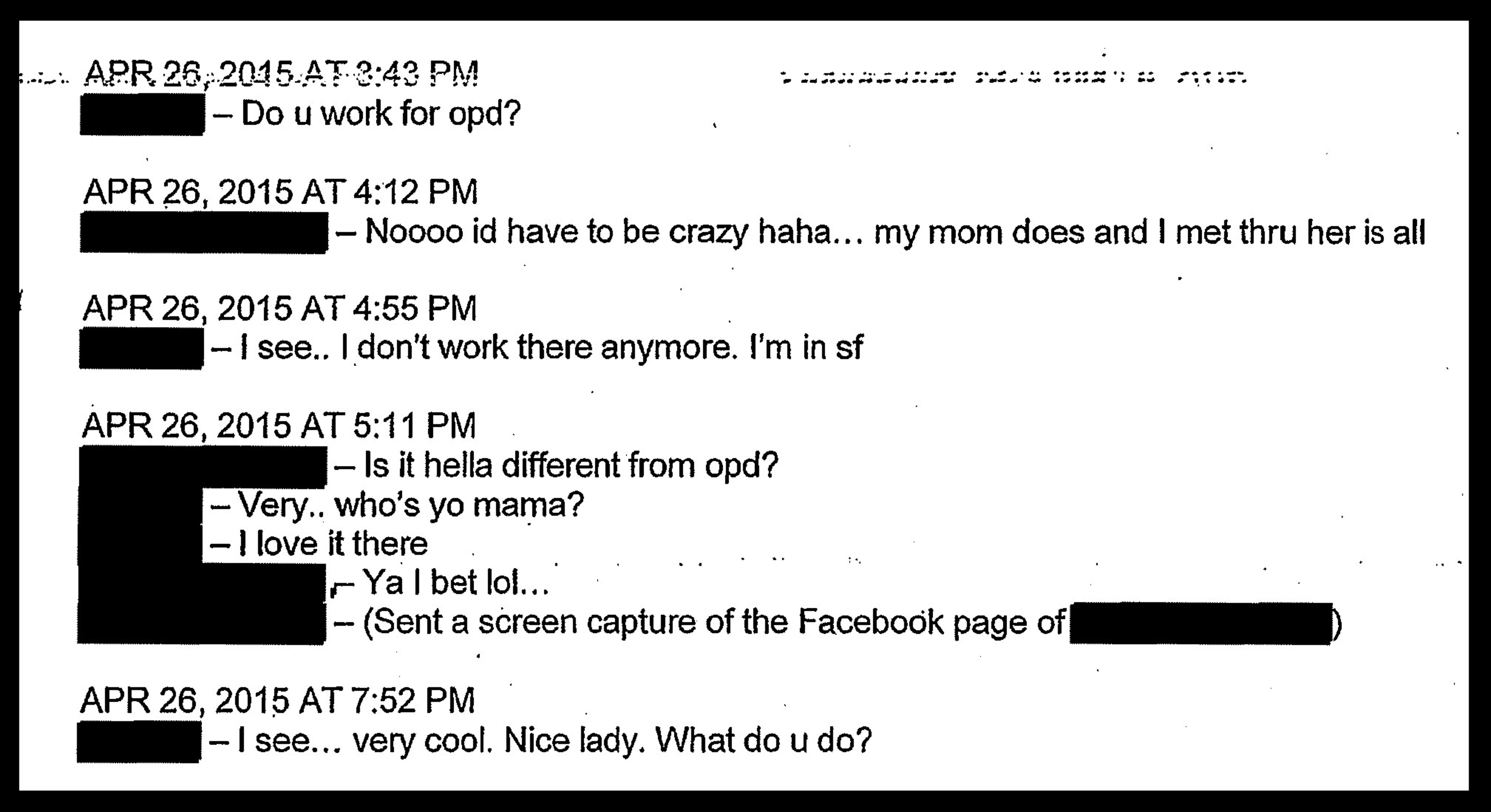

“Do u work for opd?” Ponce De Leon asked her, according to newly unsealed search warrants obtained by The Standard.

“Noooo,” Abuslin said. “Id have to be crazy haha.”

The relationship quickly turned sexual.

Months later, Abuslin told police investigators, she and Ponce De Leon exchanged nude pictures of themselves. (The search warrants don’t specify whether she shared those photos before or after she turned 18).

They first met for sex in late 2015, after her 18th birthday, when Ponce De Leon picked her up from her house in Richmond, she later told police. They drove to a nearby park where they had sex and she gave him oral sex.

They met for sex again about a month later. But this time, Abuslin said Ponce De Leon snorted cocaine that he kept in his wallet while she used methamphetamine, according to search warrants.

“Be there in 15 minutes mami,” Ponce De Leon texted her in November 2015.

“Oki:P” she responded.

The last time Abuslin said Ponce De Leon met her for sex, she invited him to a hotel by the Oakland airport where she was staying in a room booked by her pimp.

Ponce De Leon blocked Abuslin on Facebook after the sexual exploitation scandal broke that summer (opens in new tab). But it was too late.

Criminal Probe Expands

SFPD began investigating Ponce De Leon in June 2016, when an Oakland police captain probing the scandal sent the officer’s texts with Abuslin to his colleagues across the bay.

The messages spurred a criminal probe into Ponce De Leon that ensnared at least four other SFPD officers accused of either having sex with Abuslin or exchanging nude photos with her.

Abuslin told police that she had sex with a second SFPD officer at a park in Point Richmond in early 2016, and a third who took her to his home in Vacaville in April 2016 and gave her alcohol.

While names of the officers are redacted in the newly unsealed records, Abuslin identified the three she had sex with at SFPD in a later legal claim against the city as Ponce De Leon, Antonio Landi and Gregory Neal. The Standard obtained the names through a public records request.

Employees by those names are still on SFPD’s payroll, department records show. An SFPD spokesperson declined to identify the officers who allegedly had sex with Abuslin or disclose the outcomes of their investigations.

The newly unsealed records also implicate two other unnamed officers Abuslin talked to on Facebook beginning when she was a minor. Abuslin thought she exchanged nude photos with one of the officers, and said she probably did with the second. But it’s unclear what the department determined.

Records show investigators thought Ponce De Leon may have committed felony crimes including sex with a minor, possessing child pornography and sending harmful material with intent to seduce a minor. There was also the possibility of a prostitution-related agreement.

Police also investigated some of the other unnamed officers for possible crimes from exchanging nude pictures with a minor.

The criminal probe culminated with San Francisco police presenting a case against Ponce De Leon to then-Contra Costa County District Attorney Mark Peterson, who declined to file charges.

Without naming names, Peterson cleared two SFPD officers of prostitution and sex-in-public crimes (opens in new tab) for encounters with Abuslin that took place in his jurisdiction.

“Although some of the sexual acts took place in parked cars in public areas, there was no evidence that any member of the public was present, or likely to be present, or be offended,” Peterson wrote in a November 2016 press release. “According to Ms. Abuslin’s own descriptions of those incidents, no crimes occurred.”

Ponce De Leon was among a slew of officers from various Bay Area agencies cleared by Peterson. His charging decisions stood in contrast with those of the Alameda County district attorney, who filed cases against a number of officers, including two for misdemeanor engaging in a lewd act in a public place.

With the criminal probe over, SFPD investigated Ponce De Leon for potential disciplinary violations and concluded he “engaged in a number of serious internal rules violations,” court records show.

But SFPD ran into roadblocks trying to punish him.

In 2018, Ponce De Leon successfully petitioned the court to destroy evidence against him. He argued that the criminal investigators seized information from his phones and computers they had no right to take, and that internal investigators went on to improperly use it against him.

A San Francisco Superior Court judge agreed and, in 2019, ordered SFPD to destroy the evidence, court records show. SFPD responded by reducing the disciplinary charges against him to reflect the remaining evidence.

After a protracted back-and-forth with the Police Commission over how long to suspend him on what was left of his disciplinary case, Ponce De Leon agreed to a settlement in April.

He was ultimately charged with twice engaging in sexual intercourse in public and misusing his department-issued cell phone for personal reasons on and off duty.

The commission suspended him for 50 days (opens in new tab) and ordered mandatory training and a behavior health referral, holding his termination in abeyance, records show.

An SFPD spokesperson said Ponce De Leon has since “served and fulfilled the penalties and training” meted out by the Police Commission.

Ponce De Leon sued the city this past spring, claiming the department violated his peace officer protections under state law by sticking him in an “undesirable assignment” and failing to complete its investigation within the one-year statute of limitations for police facing discipline.

The city disputed the allegations, and last month, Ponce De Leon voluntarily dismissed the lawsuit.

The case was still playing out when George Floyd’s killing turned the nation’s attention to police accountability.

It began to unfold only months after SFPD faced a reckoning of its own over a series of deadly police shootings and two scandals over racist and bigoted text messages.

No one has spent longer at SFPD’s Operations Center than Ponce De Leon, records show.

Months after he settled his case, records show Ponce De Leon remained at the Operations Center. And he’s still there as of last week.

This story is the first in a series exploring the shadow system for holding officers accountable at the San Francisco Police Department. Click here for Part II.