I am on record as a critic of San Francisco’s oversized collection of toothless, performative, and time-wasting commissions. Too much nonsense surrounds these bodies, which distract city officials from conducting the important work of municipal government. It’s a more-democracy-than-we-need apparatus that has gotten so bad that we (still) have a commission that oversees a city department that doesn’t exist.

Imagine, then, my pleasant surprise to have witnessed a scene at a Small Business Commission hearing last week that proved at least some of my anti-commission priors wrong.

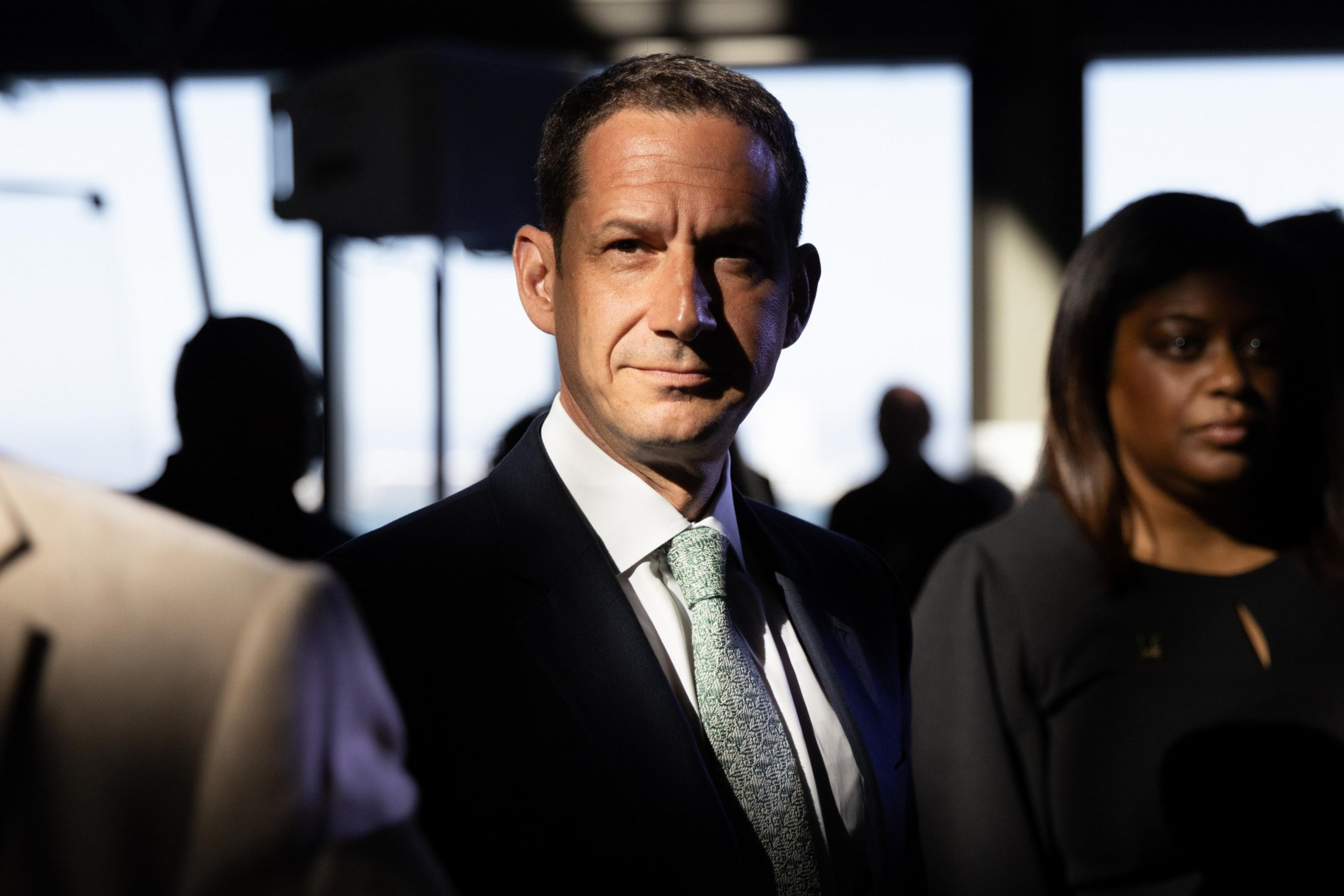

What caught my attention was an early evening exchange on Aug. 25 between Connie Chan, the leading progressive on the Board of Supervisors, and William Ortiz-Cartagena (opens in new tab), a longtime commissioner, advocate for small business, and self-described kindred spirit of Chan's. Chan was there to rally support for the extension of legislation she believes protects the little guy from big, bad capitalists. Ortiz-Cartagena, in authentic, genuine, and obviously knowledgeable language, told her the measure in question already was having the opposite effect.

The result is likely to be the gutting or outright defeat of Chan’s legislation. That would be a victory for common sense. It also would support Mayor Daniel Lurie’s efforts to make San Francisco a saner place to live and do business, a point winked at multiple times over the course of the hearing.

It’s enough to make even a skeptic think this Lurie-era “vibe shift” shtick is real.

Chan showed up because the commission planned a nonbinding vote on her bill, which aimed to continue one she co-sponsored (opens in new tab) last year with Aaron Peskin, then the board president. It made it so that if a so-called legacy business, one in place for 30 years, left a location, any business seeking to go into that spot would need something called a “conditional-use authorization” from the city.

Conditional-use permits have long gummed up the wheels of commerce in San Francisco because they allow the community to object to a new business for reasons that may or may not have any merit. For instance, posh neighbors in Lower Pacific Heights used it earlier this year to oppose a new Nordstrom concept store on Fillmore Street, raising concerns about traffic and the business’ suitability for the block. (Fortunately they were unsuccessful.)

Without a conditional-use requirement, merchants looking to open a new business can simply work out a lease with the landlord, fill out some forms, and open for service. You know — like they do in most normal cites.

Chan cast her legislation as a “modest” proposal intended to maintain the character of many neighborhoods, notably in the Richmond, which she represents. The thinking is that if the barrier is high for filling a space, then landlords will think twice about “displacing” an existing tenant. She painted a benign picture of the law’s requirements, saying that rather than banning certain businesses from entering, it simply facilitates public discussion (my italics). “That’s what this legislation is about, allowing that conversation,” she said.

(If you think that the one thing San Francisco lacks is enough public conversation, well, I have some swampland near Alligator Alcatraz I’d like to sell you.)

Chan, not surprisingly, faced ample opposition coming into the hearing. The Lurie Administration is against her bill. The Planning Department cast shade on the legislation in a May report, saying it “may not effectively support preservation goals” and might “create uncertainty for prospective tenants and buyers.” Predictably, the San Francisco Apartment Association, which represents landlords, opposes it. “This legislation does not offer a single protection for existing legacy businesses,” Charley Goss, the group’s government and community affairs manager, wrote to the Small Business Commission ahead of the hearing. “At a time when the city is focused on cutting red tape and making it easier to open and operate a small business, this proposal should be a non-starter.”

But what Chan obviously didn’t expect was opposition from the Small Business Commission itself, which has sympathy for mom-and-pop enterprises built into its DNA.

For all the slick, over-groomed, silver-tongued politicians I’ve seen in my time, including in glow-downed San Francisco, Ortiz-Cartagena was an eloquent antidote. He told Chan several times he was with her “in spirit,” that he wanted to believe that conditional-use authorizations could be an effective tool against greedy or otherwise undesirable landlords.

However, he said, the requirement she was pursuing amounted to a “hex” and “a scary thing,” especially for small businesses owned by people of color in the Mission, where he is based.

Speaking directly to Chan and wearing his trademark San Francisco Giants hat, Ortiz-Cartagana told the supervisor that conditional-use requirements favor those who can both afford expensive land-use attorneys and who have the time to wait out the city’s slow-as-molasses approval processes. He said he understands that the authorization was meant as a tool to prevent displacement, but that “in the field, it’s like getting a weapon and the weapon backfiring on you and shooting you in the foot.”

With this unexpected turn, the board dialogue devolved into some Kafkaesque maneuvering around delaying the bill’s approval, which in any event, carries no legal weight. The commission’s endorsement of this legislation would merely be a signaling event, a talking point its proponents or opponents could then take before the Board of Supervisors.

But the exchange—and the commission’s decision neither to approve nor reject the bill — did have a notable effect on Chan.

When I caught up with her later in the week she gamely called the discussion “great feedback” and said she is prepared to make amendments to her bill. “This is all part of the legislative process,” she told me. She envisions adding provisions for three types of businesses that would not need conditional-use authorization to occupy a spot vacated by a legacy business: another legacy business; a “neighborhood-anchor” business, which generally means it has been operating in San Francisco for 15 years in one location; and any business with less than $5 million in annual sales.

These would be good changes, I suppose. But here’s a better idea: How about scrapping the law altogether? I told Chan I’d like to see a drastic reduction in condition-use requirements, not an expansion of them, however many exceptions she draws up. She reminded me that she supported a recent measure (opens in new tab)that added flexibility for certain kinds of retailers.

But I still couldn’t help feeling that Chan was looking to solve a problem that simply doesn’t exist. Oftentimes legacy businesses close up shop for the obvious reason that their owners grow old and retire. Other times they fail because, ya know, that’s what happens. Protecting existing establishments at the expense of new ones is fundamentally conservative behavior, a desire to keep things as they are — the opposite of progressivism.

Chan also told me that the previous day she had gone for a walk with Mayor Lurie in her district, on Balboa Street in the Outer Richmond, to discuss his housing upzoning legislation — what he calls his “Family Zoning Plan” and she calls a 439-page “monstrosity.” She said that she is looking for a way to compromise with him on it.

“I really would love it if we could work together on this and to articulate our vision for San Francisco,” she said. She envisions an upzoning bill that enables new housing to be built without “demolishing history” in the process. She said she is cautiously optimistic about working with the mayor’s office on this issue — optimistic because she believes Lurie cares about San Francisco, cautious because of the “overwhelming” pressure from monied interests that she’s convinced could lead the city to a worse outcome.

But I have a different reason for cautious optimism. Namely that there are citizens like Ortiz-Cartagana who have the courage to speak up and call out nonsense when they see it. He showed me exactly what these citizen-advisory panels can accomplish. At their best, they are an opportunity to deliver direct feedback to politicians — and a public way to get electeds to do the right thing.

It was the rare case when the hurly burly of San Francisco’s political process actually made some sense.