Lauren Post has a unique perspective on the role of San Francisco’s 130-some commissions and advisory bodies, having served on a couple herself and even chaired one. So when she says the commission on which she’s been the chairperson since its creation no longer serves a purpose and should be eliminated, the city should listen.

“I have come to the conclusion, after chairing the Public Works Commission since its inception, that it is not needed,” Post told me over coffee last week.

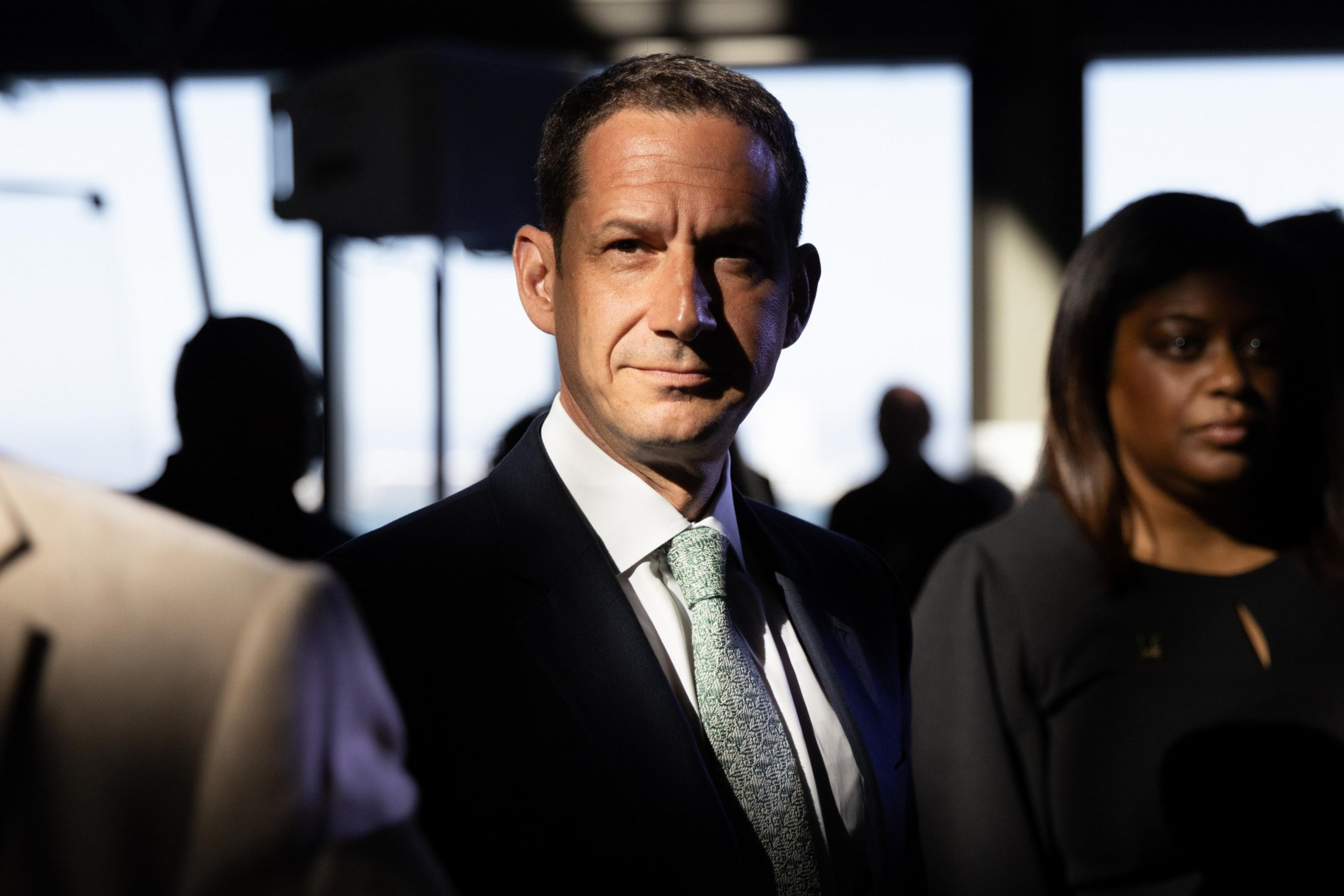

Now, before you leap to any conclusions about Post’s anti-democratic political agenda, there are some things you should know about her. A Stanford MBA and a retired investment banker who specialized in municipal bonds, she has served on a city bond oversight committee, her local community benefit district, and two other citizen committees related to the Transbay transit hub. In 2020, voters created a Public Works Commission to provide oversight of the scandal-plagued Public Works Department, and then-Controller Ben Rosenfield named her to it. She even calls herself “Ms. Civic Volunteer.”

Post is, in other words, exactly the kind of citizen San Francisco needs serving on its stuffed-to-the-gills collection of often toothless advisory committees, boards, and councils — as well as its several commissions that are critical to governing the city. Her experience gives her credibility in what is certain to be a fraught debate when the issue of what to do about these bodies comes to a head next year.

“It is my opinion, and I say this with affection, that San Francisco has an excess of democracy,” she told me. “Many people feel it's their right to have a lot of influence in how decision-makers make decisions about the government. At some point, you have to trust your government is doing its job. And if it's not, then you un-elect them. You throw them out.”

The Budget and Legislative Analyst’s office estimates that these commissions cost the city just shy of $34 million a year, or just over $300,000 per commission.

Since she was appointed to the Public Works Commission the body has done some good work, Post believes, including helping the department’s employees improve their rock-bottom morale by regularly reviewing their vital work and guiding them to adhere to a set of accountability metrics. Partly because the department is on firmer footing, she believes the commission that watches over it has outlasted its usefulness.

Post’s informed point of view is music to the ears of those of us who think our plethora of ineffectual oversight boards gums up the gears of government more than it provides useful transparency into how things work. Her chief reason for wanting to eliminate her own commission is one opponents of advisory bodies often cite: They are too much of a distraction to city personnel, who expend an excessive amount of effort responding to their requests.

“It takes a lot of staff time to prepare for our commission meetings,” she said, noting contributions from project managers, financial officials, liaisons from the City Attorney’s office, and senior management. “That’s all time they could be doing their jobs, delivering services to San Francisco.”

She also thinks her commission wastes its own time. For example, it conducted a rigorous search for a new Public Works director,ultimately landing on Carla Short, the interim director. Post said Mayor London Breed’s office ran a parallel process that would have been sufficient. “I did work almost full-time for a year on the search, and it is my opinion that the process and the outcome would have been the same with no commission involvement.”

Then there’s the cost of all this governmental cosplay. Prop E, approved by voters last year, mandated that the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s office of the Board of Supervisors make an estimate of what the city’s 130-some advisory bodies cost. Based on responses to a survey by 111 commissions, the analyst estimates that these commissions cost the city just shy of $34 million a year, or just over $300,000 per commission. That is based mostly on estimates of staff time serving the commissions, including their salaries and benefits, plus the city services they consume to operate them.

There’s an irony of how the Prop E process is playing out. Aaron Peskin, former president of the board of supervisors, placed the measure on the ballot last year to counter a competing initiative, Prop D, that would have willy-nilly chopped the roster of commissions. (Michael Moritz, chairman of the Standard, was a prominent financial backer of Prop D, which was closely — and, I would suggest, ruinously — associated with the lackluster mayoral candidacy of Mark Farrell.) While Prop D would have killed commissions outright, Prop E instead called for a Commission Streamlining Task Force to study the matter.

Post’s rhetorical hand grenade seeking to blow up her own commission is timely, as it coincides with the Prop E-mandated task force making surprising progress. In fact, it is likely to make draconian recommendations next year that promise to set up yet another showdown between good-governance advocates and those who like things the way they are. (For a recent example of these forces at play, see the bizarre feud over the Sweatfree Procurement Advisory Group I wrote about in July.)

I assumed the Commission Streamlining Task Force would be a classic Peskin kick-the-can-down-the-road vehicle. So far it hasn’t proven to be. It has been meeting regularly and already has tentatively agreed to recommend eliminating 36 volunteer bodies. Many of these are inactive, like the San Francisco Residential Hotel Operators Advisory Committee or the Street Design Review Committee. Another, the Relocation Appeals Board, oversees a state agency that has been dissolved. The task force’s work continues, and it will recommend further eliminations and consolidations in coming weeks. (It will consider the fate of the Public Works Commission on Sept. 17.)

Importantly, the body is also recommending that the mayor have the sole right to appoint members of most governance commissions — and to remove them as well. This would be a dramatic change. Right now, the mayor is saddled with appointees of his predecessor as well as designees of the Board of Supervisors, creating separate power bases on many commissions. (The task force explicitly voted to keep split appointments for the Police Commission, a notorious hot potato.)

Unsurprisingly, the proceedings of the task force have been contentious. Its chair is former controller Ed Harrington, organized labor’s representative on the panel and noted fan of commissions, while its vice-chair is Jean Fraser, head of the Presidio Trust, who was chosen by the mayor for her expertise in “open and accountable government” and has repeatedly voiced her skepticism of multiple advisory bodies. The other three positions are filled by senior officials from the offices of the City Administrator, Controller, and City Attorney.

Harrington told me last week he was frustrated by disagreements inside the task force over the fate of the volunteer bodies. “I understand [commissions] can be a pain in the ass,” he said. “But I also understand they can add value.”

There was something revelatory in how Harrington expressed his frustration to me. Prop D, he said, was about “getting rid of commissions.” Voters rejected it. Prop E, which they approved, posited that “public engagement is a good thing and that we should address the detritus,” Harrington said, meaning the bodies that constitute dead wood in the system.

His positivity about the commissions system is echoed in the text for Prop E itself, which celebrates commissions for leveraging “the perspectives, lived experiences, and expertise of the City’s residents, and ensure that important policy decisions are not made behind closed doors by a powerful few.” (If you hear the voice of Peskin in these words, you’re not alone.)

That’s all well and good. Yet the meat of the measure, the part that empowers the task force, asks it to make recommendations to the mayor and Board of Supervisors about ways “to eliminate, consolidate, or limit the powers and duties of appointive boards and commissions” to improve the administration of government.

That is exactly what the streamlining task force is doing — even if at least one of its members is queasy about the results.

This being San Francisco, getting from task-force recommendations to legislative reality will require some additional steps. Prop E made it so that the task force’s suggestions regarding changing the city charter will require approval of the Board of Supervisors and yet another voter-approved ballot initiative. Some advisory bodies are governed merely by city ordinances, and only a super-majority of eight board members can veto the task force’s recommendations to amend these.

With board scrutiny will come, you guessed it, more public comment. Recent history shows what happens when the board tries to do away with anything. Witness how Board President Rafael Mandelman was stymied during the aforementioned fight over the Sweatfree Procurement Advisory Group.

Any way you slice it, though, San Francisco voters said last year they wanted the city’s commission structure cut down to size, Post pointed out to me. The populace’s intent is clear. Said Post: “I believe voters expect results from this.”