For the first time in his nine mostly charmed months on the job, Mayor Daniel Lurie is facing some real heat. The pushback comes on the heels of the landslide recall of a supervisor who angered his constituents in the Sunset. Having tasted blood, advocates for neighborhood preservation are running exceedingly hot — and looking for their next fight.

So here they have it: The mayor’s “family zoning plan,” a sweeping effort to raise building caps and boost density across a broad swath of the city — most notably on the suburbanish west side. Into the frying pan we go.

It is a fitting symbol of San Francisco’s unique brand of civic dysfunction that nobody can even agree on what to call Lurie’s comprehensive plan. The mayor glibly calls it “family zoning”. Because, yes, housing affects families, and his label is snappier than “the-get-the-state-off-our-back-housing-appeasement plan.” A strange-bedfellows alliance of west-side-homeowner NIMBYs and anti-development progressives prefers to term it an “upzoning plan,” which is accurate, if triggering, because building upward blocks longtime homeowners’ views. And sober-minded policy wonks call it what it is: “rezoning,” or a needed and required revamp of the city’s complicated zoning code.

This is more than a spat over words. The outcome of an actual legislative battle will determine if the city can comply with a state requirement that San Francisco create the conditions to add about 36,000 new homes by 2031—or relinquish control over such matters to Sacramento. The kerfuffle, which already has played out in dueling rallies on the steps of City Hall and a 10-hour hearing at the Planning Commission, will test if Lurie can convert his first-year popularity into a major policy accomplishment — or become embroiled in the kind of tribal bickering that has bedeviled his predecessors.

Suffice it to say the debate is a hairball of legalese so arcane that (opens in new tab)the city’s own website on the subject (opens in new tab) is a jumble of color-coded maps, fact sheets, and argumentation. I’ve done my best to wade through it all, as well as the positions of the plan’s opponents. My conclusion: Lurie’s rezoning scheme is a good and necessary plan that bends over backwards to assuage many of the concerns ordinary San Franciscans (as opposed to cantankerous gadflies) will have with it.

Sarah Dennis Phillips, director of the city’s Department of Planning, is charged with implementing the plan — and selling it to the public. “We want to increase heights on transit corridors,” she told me, by way of simplifying the plan’s goals. “And to allow flexibility in the rest of the neighborhoods without increasing heights.”

It’s important to note, and Dennis Phillips has been doing it repeatedly, that nothing about the plan guarantees anything will get built. Zoning laws allow for things to happen. Furthermore, not having a plan—in this case, the Board of Supervisors not approving one by Jan. 31, 2026 — would mean the state would suspend funding and take over approving developers’ proposals, as it has done in Palo Alto, Menlo Park, Portola Valley and other communities.

These nuances haven’t stopped the plan’s opponents, who include residents nervous about what will happen to their neighborhoods, activists who fear evictions of renters and business tenants, and more than a few political rabble-rousers who see an opportunity to bloody up a mayor who’s far too popular for their taste.

Take Aaron Peskin, the former president of the Board of Supervisors, who told a community meeting in the Richmond this month: “I believe that we can build the housing that San Francisco needs and deserves without turning Ocean Beach into Miami Beach.”

It’s a good line, one he’s been using since his failed mayoral campaign last year. The problem with it, though, is that Lurie’s plan won’t allow for a Miami Beach-style, 48-story skyscraper (opens in new tab) anywhere near Ocean Beach. The tallest a building could be built on any block near the coast is six stories, only two stories more than is currently allowable — a prime example of how incremental this plan is.

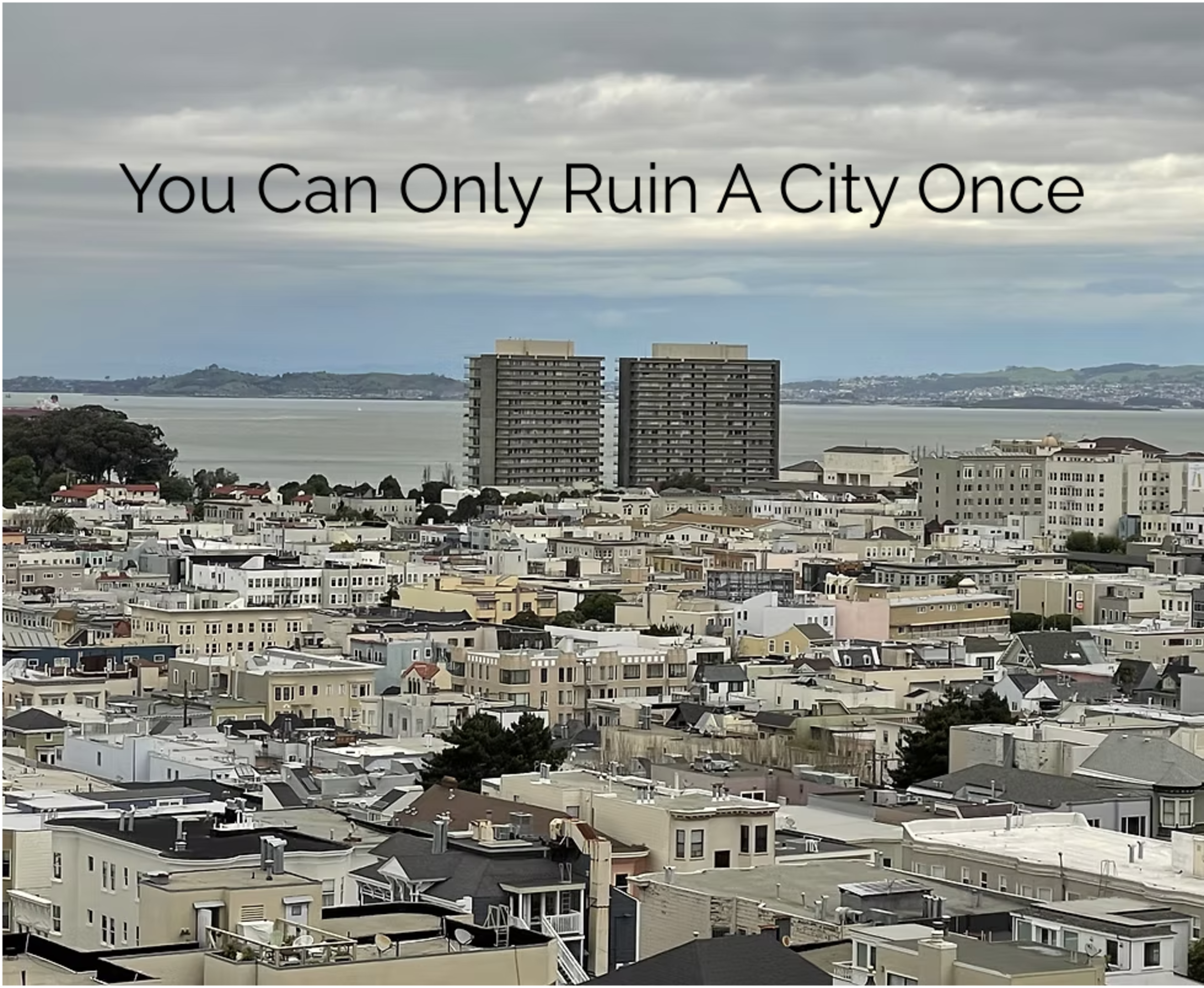

Of course, history is important here. Activists are justifiably obsessed with eyesores like the 18-floor Fontana Towers along the northern waterfront and the bitter battles of the1960s and 1970s over the “Manhattanization” of downtown. But evoking them, as the activist group Neighborhoods United SF does with a photo labeled (opens in new tab)“You Can Only Ruin A City Once,” (opens in new tab) is more scare tactic than critique.

What’s notable about the plan is its focus on the western half of the city. Past rezonings have concentrated on the city’s eastern side, notably around the now-thriving Mission Bay development. The city has been clear that in order to meet the state’s 36,000-home mandate it must address the lack of density in neighborhoods heavy with single-family homes. “The Family Zoning Plan ensures that ALL neighborhoods do their fair share,” reads one of its fact sheets.

That language reminded me of the legislation Supervisors Bilal Mahmood and Shamann Walton introduced earlier this year, the “geographic equity” ordinance, to ensure that homeless shelters and services facilities get built in every part of the city.

I asked Walton if he planned to vote in favor of the mayor’s plan, given that it does something similar to what his and Mahmood’s homelessness proposal would have, while mandating no changes in District 10, the southeastern section of the city he represents. In a text-message exchange, he told me he hasn’t decided yet. But he shared his litany of concerns, which serve as a neat summation of the progressive theory of the case against the plan: “Not 100% sure this will equate to building on the Westside. No financing with the zoning plan, no projects in the pipeline, no will to build on the Westside and not sure if rent control, businesses and affordable housing will be protected or created in this plan.”

Walton’s skepticism is warranted, because it’s true that the plan guarantees nothing, including no financing mechanism that would help the city meet its housing goals. That’s because zoning plans are about zoning, not financing. There’s nothing stopping the Board of Supervisors from appropriating money alongside the zoning plan.

In fact, his colleagues Myrna Melgar and Chyanne Chen have introduced a bevy of ordinances to strengthen rent controls, provide for tenant protection, and stand up a Small Business Rezoning Construction Relief Fund (of an unspecified amount) to aid the low number of businesses that might be displaced by new developments. Their legislation mirrors a long list of demands another supervisor, Connie Chan, sent to the Planning Department. On the sacred-cow issue of rent control in particular, the city contends that existing protections ensure that little will change. “Right now, the only way to demolish any rent-controlled housing is to go before the Planning Commission and ask for permission,” said Dennis Phillips. “And the commission almost never grants that permission.”

At a certain point, with something as complicated and hotly (and endlessly) debated as this plan, there comes a point when citizens need to stop digging into maps and shouting about demands that are actually being addressed. They need to trust their elected representatives and public servants to do their jobs. And if they’re that upset about their electeds’ votes, they can show them the door next time they come up for election.

But it’s time to stop obstructing and obfuscating this plan, no matter what you want to call it.