Two weeks after withholding $1 billion in homelessness funding over lackluster local plans, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced Friday that most cities and counties would get the funds as early as next week anyway—as long as in the next round, they commit to more aggressive plans to reduce street homelessness.

But it’s been a whiplash-inducing couple of weeks, triggered by a funding process that frustrated both the governor and the locals. Newsom dissed local applicants for seeming too complacent about a dire California problem, while the applicants retorted that the Newsom administration sent conflicting signals—and that in any case, state lawmakers had inadvertently given them a financial motive to lowball their goals.

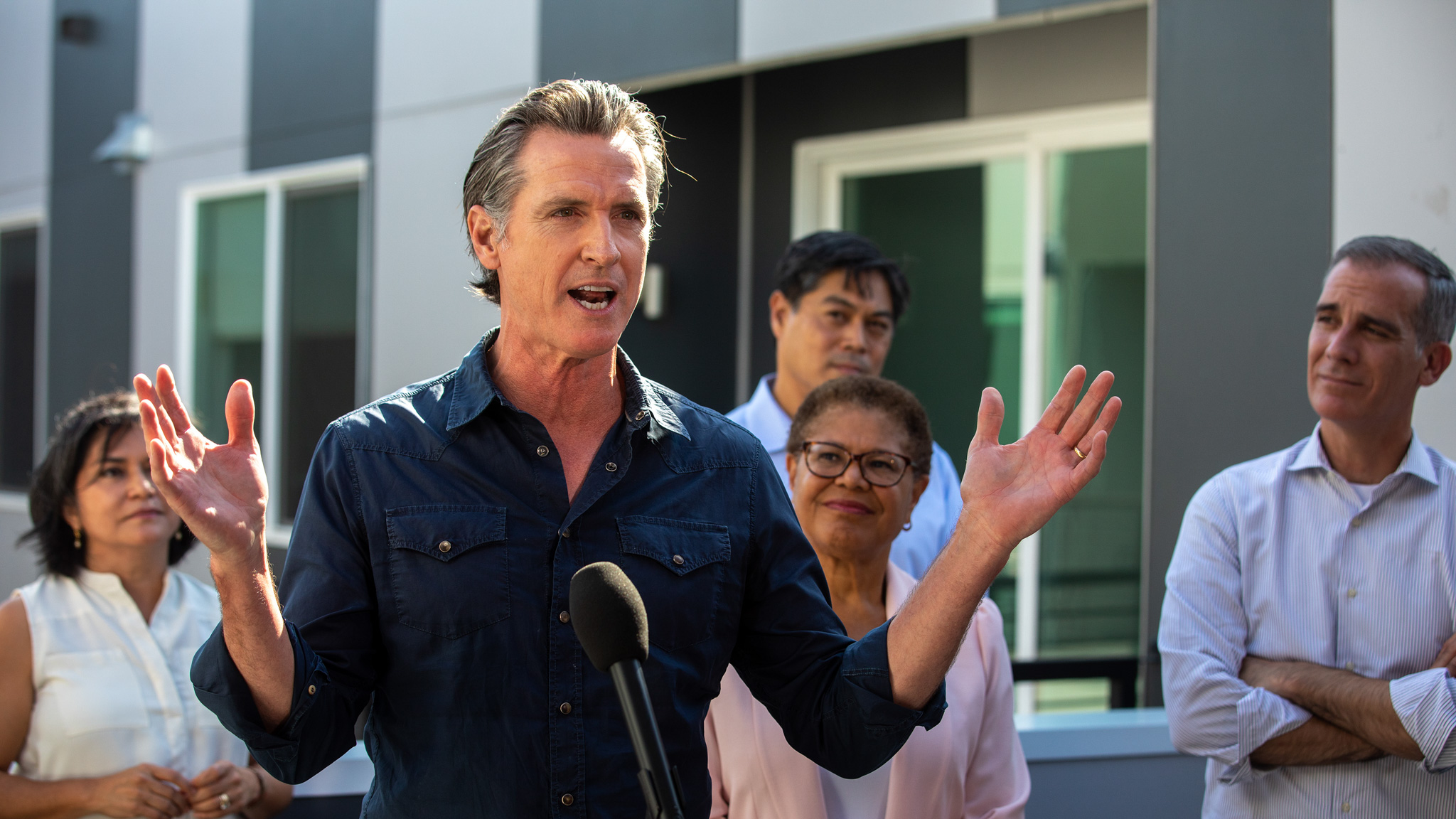

More than 100 local mayors and county officials gathered virtually and in-person in a sleek downtown Sacramento government building Friday afternoon to broadly discuss how to better tackle the state’s most pernicious crisis.

“It was nice to hear their progress, and it was nice to hear their recognition that we have to get to another level,” Newsom told reporters following the over two hour-long private meeting.

It was a quick reversal some local leaders and advocates saw as a political stunt: The episode gave everyone a chance to air their grievances, but landed on no specific targets, while briefly risking the continuity of services for people experiencing homelessness.

“If you asked me what emerged from the meeting, I don’t know. I did not hear any specific policy changes,” said Sam Liccardo, mayor of San Jose. But, he added, “Nobody’s going to criticize the state or the governor at a time when it’s critical to get resources to bring people out of the cold. Lives depend on this.”

Other local leaders said they welcomed the prodding.

“Sometimes, you have to provoke,” said Darrel Steinberg, mayor of Sacramento. “And then gather around a table like we did today, and actually talk about what it’s going to take to provide a further jolt to this problem.”

The governor sent shockwaves through the state two weeks ago, just days before Election Day, when he summarily rejected every local homeless action plan. On the line: nearly $1 billion in homelessness funding. The plans, altogether, promised to reduce visible street homelessness by 2% between 2020 and 2024—or 2,000 fewer people statewide—which Newsom had called “simply unacceptable.”

His move triggered chaos among many of the 13 largest cities, 58 counties and 44 homeless service providers who went through the process. Many of them thought they had been approved after workshopping the plans with Newsom’s own homelessness agency, only to learn of their rejection en masse.

But local governments didn’t have much of an incentive to shoot for the stars in their plans, either, because of the way the governor and Legislature wrote the grant. In the name of accountability, they tied nearly a fifth of the $1 billion to local governments meeting their own unsheltered targets. With more people falling into homelessness than they can catch, many felt ambition might set them up for failure.

That criticism came up during the meeting, Newsom told reporters, holding up yellow pages ripped from a notepad.

“We worked with 120 members of the Legislature to put this forward,” he chuckled. “And now we’re working with 75 jurisdictions on these plans. … In fact, literally right here, the recommendations: ‘What specifically do you want to change in terms of these metrics and plans?’ And that’s exactly what this conversation was about going forward.”

As soon as applicants sign a pledge to submit more ambitious unsheltered targets and try harder in their plans for the next $1 billion grant—the final round of flexible local homelessness funding approved in the 2021 budget—the state will start cutting checks for this round, according to Jason Elliott, Newsom’s deputy chief of staff. Those new plans are due Nov. 29. A handful of local governments will have to work with the state to adjust their current plans before seeing the funding, although Elliott declined to name which ones.

Punishing the Emergency Room

During the pandemic, homelessness only spiked, and experts expect to continue to see its fallout on the streets in the coming years as rental assistance and eviction bans end. Between 2019 and 2022, homelessness increased by at least 22,500, to 173,800 people statewide, according to a CalMatters analysis of local point-in-time counts. Nearly 70% of those people were sleeping outdoors or in vehicles, while the rest stayed in shelters and transitional housing. (These biennial visual head counts on a given night often are criticized for their inaccuracies.)

Yet the state asked cities and counties to calculate their 2024 goals based on their lower pre-pandemic counts of homeless people. At the time the application was due this summer, most localities simply figured they couldn’t promise to make homelessness that much better when it had already grown so much worse, and was on track to keep worsening. And being too ambitious risked failure to meet their targets and losing any shot at the bonus money.

Newsom saw what they did and cried foul. He called out the Sacramento region in particular—though not by name—for its lack of ambition: Instead of promising a reduction, the local governments and service providers foresaw a 71% hike in homelessness in their report. Why? That’s exactly how much homelessness had already risen in the capital city this year, and the latest data that would be available by the time communities were evaluated on their progress to qualify for $180 million in bonus funding statewide.

Comparing the relatively current 2022 numbers with the 2024 goals, communities had really signed up for a 4% or 5,000 person reduction, according to a CalMatters analysis—which if achieved would be better than the state has done in years. Since 2015, homelessness has only increased in California, by an average of 7% a year, or about 8,300 people.

After the turmoil of the past couple of weeks, Steinberg said Sacramento has now put forth a new goal, promising a reduction of 15%, or 1,000 fewer unsheltered people, by 2024. How progress might be measured differently remains unclear.

The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, which promised a 10% decline, or 4,600 less unsheltered people between 2020 and 2024, took a similar approach.

“If the (count) alone can mean that we receive 0% of the bonus funding, of course we’re going to approach it conservatively,” said Molly Rysman, the authority’s chief program officer.

Still, Newsom had a point: Some regions had set targets that would represent more than 30% growth between 2022 and their 2024 goals. Bakersfield, for example, initially promised to lower street homelessness by 1%. But after a big fall in unsheltered homelessness this year, their new goal would represent a hike of 37%, or 266 people.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development—which mandates the homeless count—has often advised against tying it to funding because shooting for a certain number could influence its accuracy. Still, the point-in-time count remains the only uniform way to measure the number of people sleeping on the streets.

“It’s imperfect at the moment and over the years. … I hope we can evolve and consider different strategies,” Newsom said, suggesting the count can miss homeless people who are less visible. “Now what I see is what I see on the streets. And that’s a challenge.”

The federal department instead advises measuring success using the count in conjunction with other outcomes, like higher placements into permanent housing or fewer returns to homelessness.

“If I see positive trends in those other areas, and either stagnation or maybe just a slight downturn in the (count) that’s actually probably a positive thing,” a HUD spokesperson who would only speak anonymously told CalMatters.

California, like many other states, has seen a massive jump in homelessness since 2015, “way beyond the great work that many communities are doing to house people,” the spokesperson added. The driver: a housing shortage propelling skyrocketing rents.

Newsom himself promised to abate that shortage when he first ran for governor, vowing to oversee the building of 3.5 million homes. He’s fallen dramatically short of his goals.

Local service providers felt unfairly stung by Newsom’s criticism because they have no control over housing unaffordability and the other system failures that cause homelessness. And while they are getting more state funds than ever before, their resources don’t match demand. Funding the current affordable housing need alone would require nearly $18 billion a year, according to an analysis from Housing California and California Housing Partnership, two affordable housing policy advocacy groups.

“This would be like the governor saying, I’m going to hold funding to emergency departments because the number of car accidents in your community hasn’t gone down,” said Anna Laven, executive director of the Bakersfield Kern Regional Homeless Collaborative. The collaborative is one of 44 “continuums of care” in California that oversee the region’s homelessness response and applied for the grants in conjunction with city and county governments.

‘He surprised everyone’

When Newsom withheld the funds earlier this month, service providers were aghast.

“He surprised everyone, up and down the state,” said Stephen Simon, interim executive director of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, another continuum of care.

Laven, from Bakersfield, shared with CalMatters a Sept. 1 email from the California Interagency Council on Homelessness—which ultimately reports to Newsom— saying their application had been “moved forward for final review in preparation for the award and disbursement process.” She thought it had been approved. But when she asked for a contract and check, it never came. Instead, they got additional questions about their application weeks later, which she thought was a mistake. Then came Newsom’s announcement that he was yanking the money.

“We were all feeling pretty blindsided and, you know, sort of reeling,” she said.

The council “conducted intensive technical assistance over a six-month period” with all applicants, grants director Victor Duron reported during a Nov. 10 meeting. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority said its own meetings with the council had gone so well, it had already struck contracts, including one to fund more than 1,000 interim housing beds, with its $84 million share.

“They wanted to see impact as soon as possible, and so we followed that guidance and allocated all of the dollars,” said the authority’s Rysman.

The state had approved none of the applications before requesting additional information, according to Lourdes Castro Ramírez, secretary of the Business, Consumer Services and Housing Agency, which directly oversees the council. She told CalMatters “there was no conflicting communication” from her agency and the governor’s office.

“At the end of the day we all have the same goal,” said Laven of Bakersfield. “I just wish we were working together.”