Thirty-one years ago, supervisors in San Francisco passed a landmark piece of legislation as a signal of the city’s commitment to the environment and conserving water.

Any new buildings that were bigger than 40,000 square feet and located in designated zones on the city’s west and east sides would be required to have “purple pipes.” These pipes, which are literally required to be the color purple, would be installed to transport water from a recycled water plant. Wastewater—known as blackwater—would be tested, treated and cleaned, vetted again, and then shipped back to the source to be reused for non-potable purposes, such as flushing toilets and irrigating landscapes.

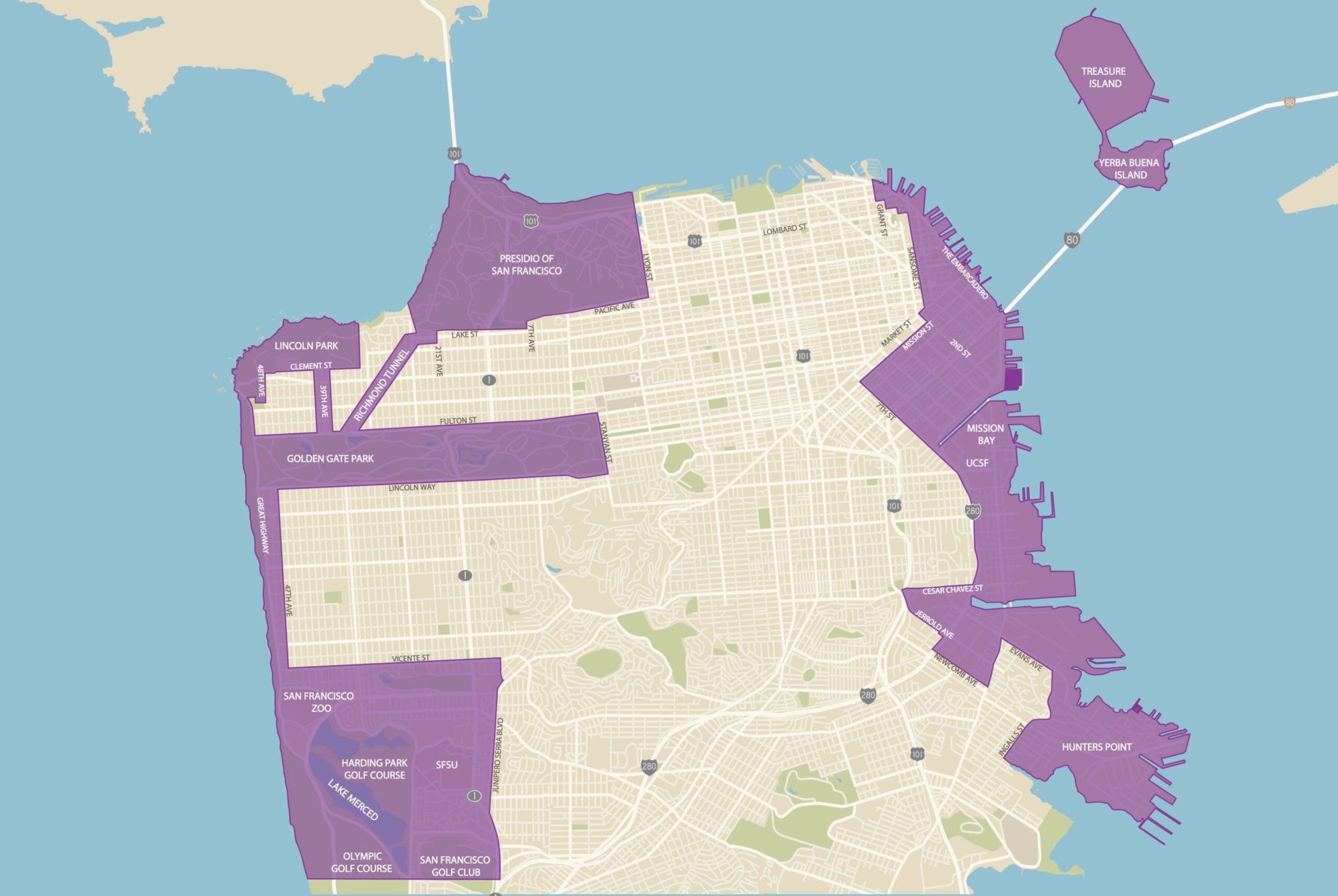

Over the last three decades, San Francisco has seen more than 70 structures go up with dual-plumbing systems that separate potable from recycled water. The buildings can be found in SoMa, Mission Bay, Hunters Point, Lake Merced and other neighborhoods—zones colloquially called “Purple Pipe Districts”—and they range from multi-unit dwellings to high-rises that shoot up dozens of stories, including the city’s tallest structure: Salesforce Tower.

But there’s just one problem.

San Francisco never built a recycled water treatment plant for these buildings. Since the city passed the groundbreaking legislation in 1991, it hasn’t come close to building the facilities it needs to realize its big water dreams. A recycled water plant that will open on the west side next year will only serve parks and golf courses.

In all but one instance, San Francisco’s purple pipes lead to nowhere.

‘Potemkin Environmentalism’

California is currently going through a mega-drought not seen in 1,200 years (opens in new tab), and San Francisco has seen its once-ample access to water curtailed by several court challenges. The city could really feel the squeeze in years to come as environmental pressure builds on its main source of water, the Tuolumne River.

Meanwhile, every building in San Francisco with purple pipes—except for Salesforce Tower—is flushing its toilets with Hetch Hetchy reservoir water that is clean enough to drink. And the cost of San Francisco’s inaction can be measured in more than cubic feet.

Officials for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), which manages water for 2.7 million people and sells water to 26 other agencies, said they have no idea how much money has been spent installing purple pipes over the years. But sources familiar with dual plumbing operations told The Standard that large projects can incur costs in the hundreds of thousands, if not more than a million.

This money gets spread across a project, from planning and materials to additional labor. Developers who have built housing and commercial spaces in San Francisco’s purple pipe districts have almost certainly passed along these extra costs to residents and tenants.

Patrick Kennedy, a Bay Area developer with more than 30 years of experience, said that purple pipes may sound “benign,” but the extra costs have a chilling effect on developers in the current climate. He called the city’s purple pipes program an example of “Potemkin environmentalism.”

The facade of a progressive policy that doesn’t actually do what it portends is likely to remain in place, Kennedy said, as elected officials are currently facing great pressure to address the city’s most visible crises: homelessness, crime and rampant drug use on the streets.

“I think it’s more for the bragging rights than anything else,” said Kennedy, who owns the firm Panoramic Interests. The developer said he seriously doubted the city would drop hundreds of millions of dollars “on a graywater system when we have all of these other unresolved problems.”

San Francisco will open a recycled water plant on the west side (opens in new tab) of the city next spring, but this $216 million facility will not connect to any buildings but instead irrigate Golden Gate Park, Lincoln Park Golf Course, the Presidio and other landscaping areas.

The latest attempt to build a recycled water facility on the city’s east side, where the buildings with purple pipes are located, fizzled this spring after officials deemed the price tag prohibitive.

A report in April found that the total cost of creating a recycled water plant in Mission Bay—from acquiring the property and building the facility to digging up the streets to install the pipelines—would run as high as $185 million.

“I feel like we need to figure out where we’re going with this,” said Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, who has been working with the SFPUC and the plumbers and pipefitters union UA Local 38 to see what might be possible. “We are heading into a period of serious water shortage and we are going to need a recycling plant.”

Dave Feahy, who oversees business development for Local 38, said the “big trick to the puzzle” would be figuring out how to get the piping and infrastructure under the streets without too much disruption. “That’s the hard part,” he said.

Paula Kehoe, the director of water resources for the SFPUC, did note in an interview that buildings with purple pipes are better situated in the event that a recycled water plant gets built. Multiple experts agreed that retrofitting these buildings would cost exponentially more than installing the pipes at the outset.

But city officials on all sides acknowledge that the purple pipes program has failed to date.

“I could certainly see people being frustrated by it, yes, and that’s why we haven’t given up on the topic,” Kehoe said. “We recognize we’re not addressing it.”

Good Intentions

Salesforce Tower is an exceptional building in San Francisco, but not just because of its size and notable shape. Before erecting the nearly 1,000-foot tower, the owners of the building, Boston Properties, joined with Salesforce and city officials to come up with a plan to retrofit a graywater system in an adjacent building while also building out an on-site recycled water system to treat “black” water. Blackwater contains human waste, while graywater usually consists of runoff from sinks, baths, laundromats and kitchens.

Altogether, the on-site system at Salesforce recycles about 7.8 million gallons of water a year, which comes out to the same amount of water 16,000 residents would use in a year, according to the company.

“Drought is persistent in the state of California and in and around the Bay,” said Amanda von Almen, head of emissions reductions at Salesforce. “We really wanted to make sure that when we were addressing sustainability of the building, we were thinking about it locally. ‘What are the local issues? What are the environmental factors to consider?’ It became obvious that we needed to do something about water and really showed some leadership there.”

In an effort to buffer the feckless purple pipes program, San Francisco officials created an on-site water reuse program in 2012 to collect, treat and provide water for non-potable purposes. State Sen. Scott Wiener expanded on this program in 2015—when he was still a supervisor—by forcing private developers to install on-site water reuse systems in any property over 250,000 square feet. That requirement dropped to 100,000 square feet in October of last year.

City officials are sensitive to the fact that the purple pipes program has never come to fruition, and they point with pride to facilities that do the dirty work (opens in new tab) of treating their own water in-house.

The Chase Center, an 11-acre spread that serves as the home of the Golden State Warriors, has an on-site water treatment system that saves 3.8 million gallons of potable water each year. Moscone Center, which covers a staggering 1.5 million square feet, has a large on-site water system that harvests, treats, and reuses rainwater and drainage from multiple locations in an effort to export more non-potable water than the convention center consumes. Anchor Brewery received a million-dollar grant (opens in new tab) to save water and the developing mixed-use neighborhood Mission Rock—spread out over 28 acres—will feature a district-scale project to treat blackwater for up to 11 buildings.

In total, the city has almost 60 voluntary on-site water recycling projects in various stages of design, construction, permitting and operation, according to the SFPUC.

But these are all unique projects and large-scale venues that have the ability to cover the substantial cost of on-site water systems. Smaller developments would struggle to make an economically feasible plan that pencils out, Kennedy said. And, of course, this does nothing to solve the missing link for buildings that were required to install purple pipes.

Salesforce officials declined to reveal how much their recycled water system cost to create, but a recycled water system called the “Living Machine” at the SFPUC headquarters on Golden Gate Avenue reportedly cost the utility $1 million.

Steve Panelli, the chief plumbing inspector for the Department of Building Inspections, told The Standard that the city may have been a bit premature in launching its purple pipes program in 1991, but needed to start somewhere.

“I do think everyone’s intentions were good,” Panelli said. “When it gets done—great. I just don’t know when it will happen.”

‘Mad Max Style’

If San Francisco had followed through on building a recycled water plant to connect to its purple pipes, the city could be saving up to 438 million gallons of water every year. By no means would this make San Francisco drought-proof, but every drop will matter in the years to come. A report from the governor’s office (opens in new tab) last month predicted the state’s water supply could drop by 10% by 2040.

One person who seems less keen on San Francisco investing almost $200 million into a recycled water plant is perhaps its leading expert on the future of water.

Newsha K. Ajami, an SFPUC commissioner and director of urban water policy at Stanford University, told The Standard in an interview last week that the on-site reuse model is a more logical step as the city tries to build out a more “diverse portfolio” of water conservation models.

“In my professional opinion, I think on-site is the way to go,” said Ajami, who clarified that she was speaking as a water researcher and not in her capacity as a commissioner. “You have to start with the building blocks of building recycled water into our water portfolio, meaning we have to start with the smallest units in homes and buildings and gradually build up. And then we go to neighborhoods and city services areas.”

Gary Kremen, a director for the Santa Clara Valley Water District in the South Bay, suggested that San Francisco could find itself in a tough situation in the years to come, as a prolonged drought combined with water diverted from the Tuolumne River to farming communities could leave San Francisco thirsty for options.

“Without more conservation, San Francisco could be in a really tricky position,” Kremen said. “I can see the price of water not only heading at twice the rate of inflation but eventually surpassing the cost of gasoline—kind of Mad Max style.”

Forget the meek. Burning Man fans will inherit the earth.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly noted the way wastewater is transported. Sewage lines transport wastewater from buildings and purple pipes would transport recycled water back to these buildings.