A nonprofit that was referred to the FBI for allegedly mismanaging housing and shelters for homeless people in San Francisco gave a significant chunk of its spaces to house family, friends and employees of the group’s CEO, The Standard has learned.

While the City Controller’s Office released an audit (opens in new tab) Thursday that found a pattern of mismanagement and financial misconduct at the United Council of Human Services (UCHS), sources said the issues at the Bayview-based nonprofit—which received $28 million in city and federal grants—go much deeper.

City officials were so alarmed with the situation at UCHS that they stopped requesting federal reimbursements in the spring. This left San Francisco taxpayers to essentially pick up the multi-million dollar tab as UCHS provided housing to around 20 of its own workers—some of whom are relatives and longtime friends of the nonprofit’s CEO, Gwendolyn Westbrook.

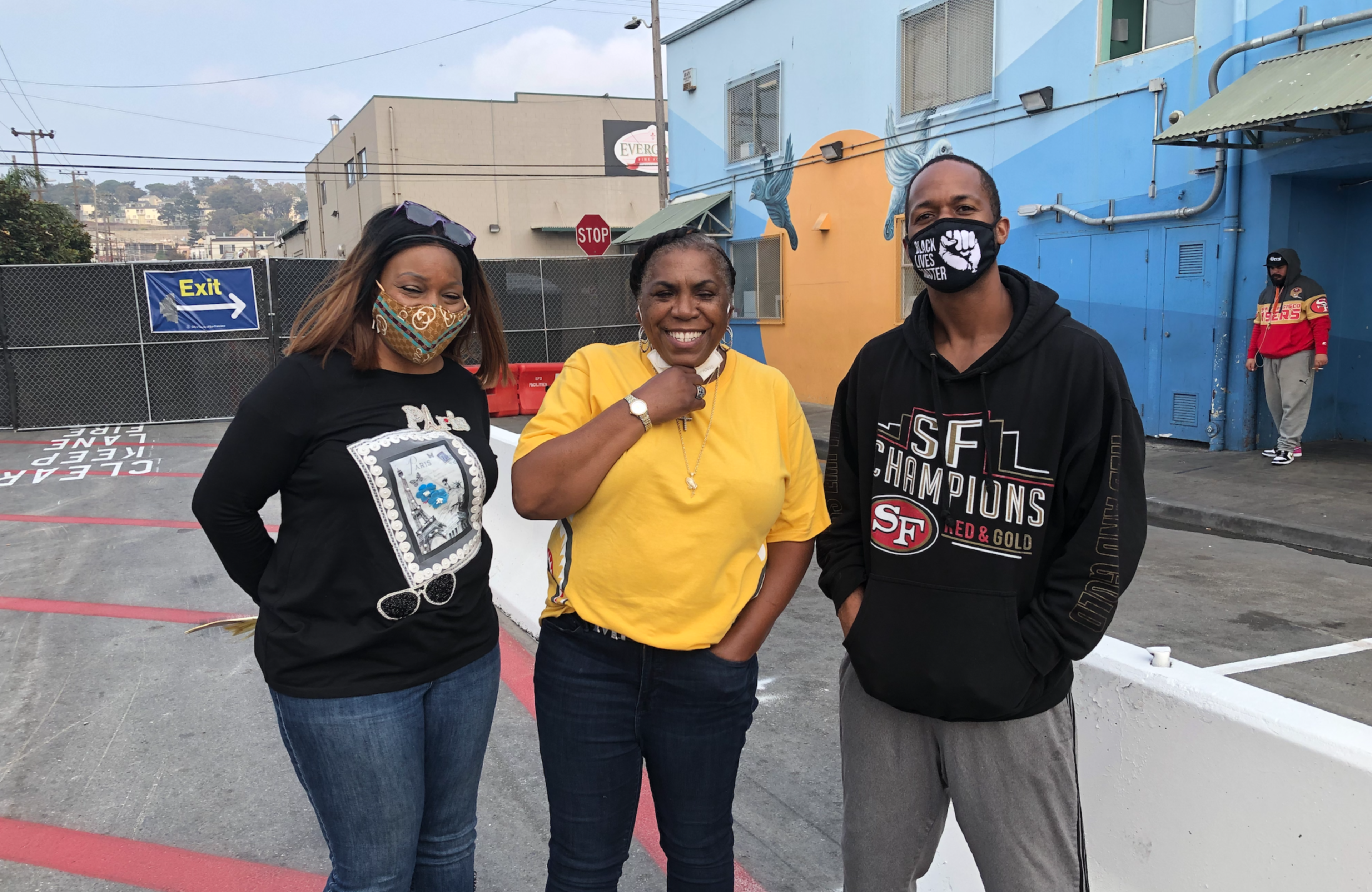

In an exclusive interview Friday, Westbrook confirmed that many of her employees—longtime friends more often than blood relatives—are taking up housing that was designed to go to San Francisco’s neediest residents.

“That’s what we’re supposed to do,” Westbrook said, adding that all of these people were previously homeless and have the proper documentation to prove it. “It might have been more [than 20 employees]. It might be less.”

Westbrook, 67, said she has documentation to show all rules were followed, although the audit said numerous records are missing or incomplete, which was confirmed and multiple sources. Westbrook accused the City Controller’s Office of lying in its audit and targeting her because she is Black. And she welcomed an FBI investigation.

“The last thing I’m gonna do is rip something off,” Westbrook said. “I came up in the city with a love in my heart for my city. And I’m in Bayview working with my people and anybody else who needs help. And I’m gonna start stealing from them?”

The controller’s audit found that UCHS, which operates the Mother Brown’s free meal program (opens in new tab) and receives federal funding for its housing sites, had not properly vetted tenants or ensured that they were processed appropriately through the city’s system for homeless individuals.

The city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, which requested the controller’s review, expressed concern that the nonprofit has used rent from clients to cover other ineligible expenses.

In a Nov. 17 letter to the FBI’s San Francisco office and the District Attorney’s white collar crime division, City Controller Ben Rosenfield and City Attorney David Chiu wrote that “access to housing was illegally sold to some residents.”

In February, the city helped bring on the Bayview Hunters Point Foundation as a fiscal sponsor to help UCHS with its financial management. The foundation, which also took over HR responsibilities for around 80 UCHS employees, received $36.4 million to help facilitate UCHS’s work in managing Hope House Consolidated, Hope House for Veterans, the Bayview Drop-in Resource Center, Jennings Safe Sleeping Village and a shelter-in-place site at Pier 94.

But in April, just two months after partnering with UCHS, foundation officials were so concerned about Westbrook’s bookkeeping that they attempted to sever ties, sources said. UCHS, which was also the subject of a critical audit in 2017, allegedly failed to pay at least $30,661 in rent and double-billed its fiscal sponsor.

Multiple sources confirmed that city officials pleaded with the foundation to remain on as a fiscal sponsor, as there are few organizations that offer homeless shelter programs in the Bayview, one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Westbrook confirmed the timeline of events involving the conflict with her group’s previous fiscal sponsor—that role is now being filled by Felton Institute—but she accused the Bayview Hunters Point Foundation of being the one that mismanaged money.

“I realized they didn’t know what the hell they were doing and called them out on it like I usually do,” Westbrook said. “They thought I was going to beg, ‘Oh, stay with us, stay with us. It will work. No. You guys are stealing. You started stealing from Day One.’ And you think I’m going to let you keep using me in this community? No.”

James Bouquin, executive director of the Bayview Hunters Point Foundation, disputed Westbrook’s allegation.

“We participated fully and eagerly in the controller’s audit,” Bouquin said. “The audit speaks for itself.”

Many within City Hall are now questioning why UCHS was allowed to continue receiving millions of dollars in city and federal grants after a 2017 audit raised concerns similar to Thursday’s report.

“It’s horrible,” said Supervisor Ahsha Safaí, who has called for the Controller’s Office to perform a comprehensive audit of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “This is precisely the reason why we put Prop. C on the ballot. Look around the city—people know we’re spending around a billion dollars to address our homelessness crisis and people are still sprawled out on the street, veterans are unhoused and people are still not getting the services they deserve.”

Emily Cohen, a spokesperson for the Department of Homelessness, said the agency welcomes transparency and hopes “the Felton Institute will bring a level of stability and compliance to United Council.”

This is far from the first time UCHS’s leader has run into trouble. Westbrook has a history of financial impropriety, as well as deep connections to some of San Francisco’s most powerful politicians.

Seven years ago, she was found to be using the UCHS to run an illicit bingo hall in Richmond (opens in new tab) that operated without that city’s knowledge. Westbrook also has a prior conviction for grand theft and misappropriation of public funds. In 1997, she pleaded guilty to stealing thousands of dollars in parking lot collections (opens in new tab) from the Port of San Francisco.

Westbrook is known as a prominent figure in the Bayview, and she has formed close ties with some of the city’s top elected officials, including Mayor London Breed and District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton. Westbrook has made political contributions to both over the years but disputed that her relationship with the mayor and the president of the Board of Supervisors had any effect on her organization receiving millions of dollars in city contracts.

“All they have given me is good advice—period,” Westbrook said. “And it was really, with the mayor, the only thing I said to her is: ‘I will not embarrass you. You will not hear me in the paper with people accusing me of doing something I didn’t do.’ And I’ve always kept my paperwork together, so I’m not getting this at all.”