Marin County kicked off a new pilot program this week that tests wastewater for traces of opioids and other drugs in an effort to measure the county’s substance use and the prevalence of deadly drugs like fentanyl. Marin is now testing for fentanyl, cocaine, nicotine and methamphetamine in its wastewater.

The coastal region is perhaps better known for its stunning waterfalls and wildlife, but it has quietly struggled with a growing drug crisis: Fatal overdoses and drug poisonings have doubled since 2020, and fentanyl accounted for 57% of the county’s fatal overdoses in 2021, according to a Marin County report.

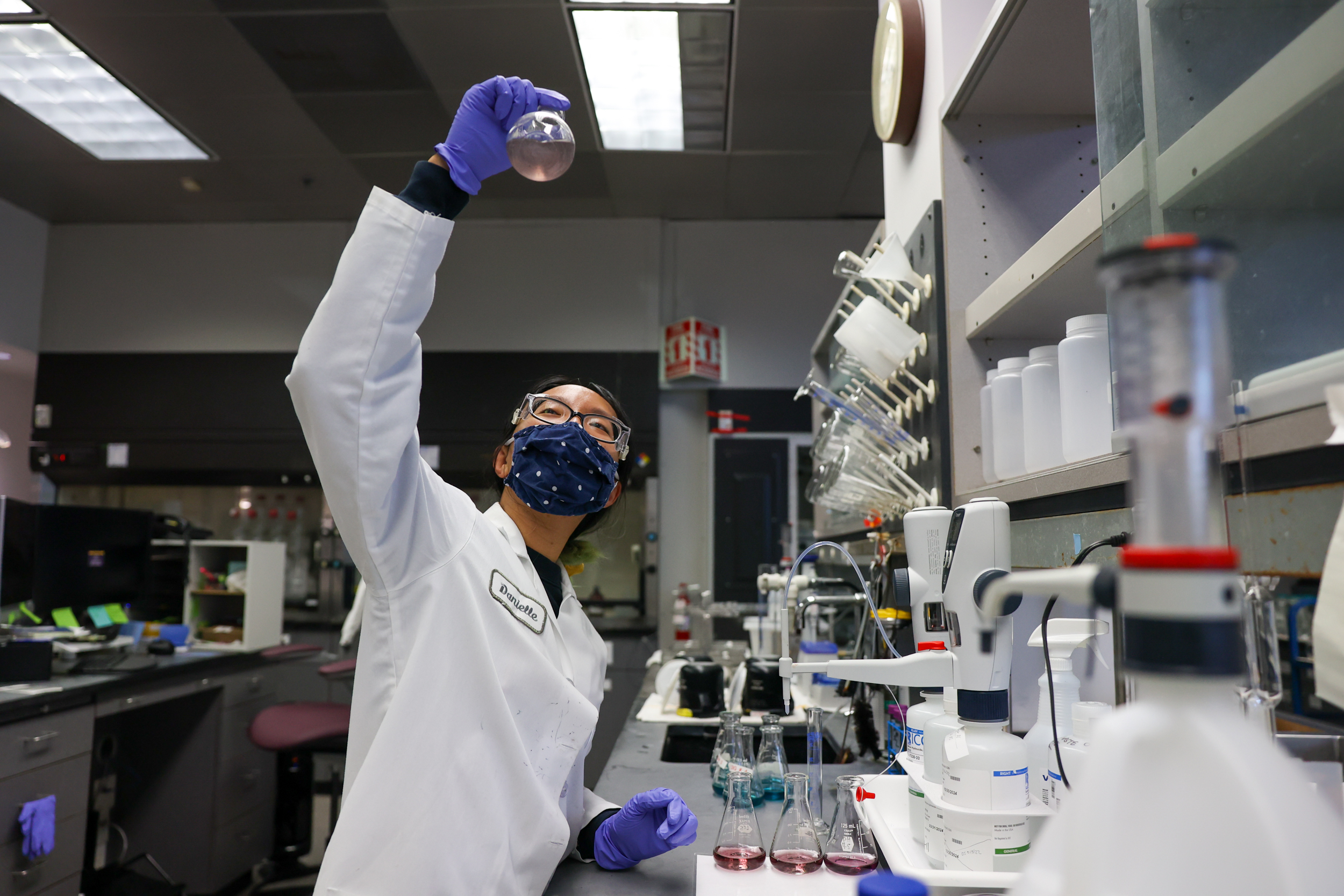

Hundreds of wastewater plants exist across the county, and the plants have been a core part of city infrastructure and community health programs for years. During the pandemic, interest in these research labs took off as many counties turned to wastewater testing to trace community Covid concentrations and to measure the spread of viral pathogens.

Now, as opioid-related overdoses and incidents skyrocket, wastewater testing programs are expanding their scope to include chemical tracing for drugs and other health metrics.

“Wastewater is a mirror of all human activities and human well-being,” said Rolf Halden, a professor and sustainability scientist at Arizona State University. “There are hundreds if not thousands of markers that can be utilized to tell us how we are doing as humanity, as a population or a community. It’s an underutilized tool.”

Municipalities and research labs across the nation have started to implement this new technology. The National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS), for example, offers wastewater analyses of fentanyl for three major cities, and researchers in Tempe, Arizona, established an open-access wastewater monitoring network to track everything from Covid transmission to community drug use.

Marin may be the first Bay Area county to formally implement a wastewater drug-tracing pilot. The effort is spearheaded by the county’s department of health and human services and wastewater epidemiology company, Biobot Analytics. The testing is carried out by the Central Marin Sanitation Agency. One of its principal investigators, Haylea Hannah, said that the pilot was made possible by a Marin County innovation award.

“We’re utilizing wastewater testing to identify spikes and trends, so we can try to respond ahead of time,” Hannah said. “We’re recognizing that our clinical data systems are not capturing all of the cases and the drug use that is really happening in the community.”

Decreasing Stigma

Though cities have attempted to measure fentanyl prevalence through analyzing drug seizures and overdose death statistics, wastewater data provides a broader, communitywide approach to the issue. This approach effectively anonymizes drug usage, focusing on overall community wellness and making it difficult for law enforcement to target individual users.

“Wastewater is a pretty agnostic technology that can be applied to different geographies and populations, and yield information on our relationship to the use of substances,” Halden said. “That information is somewhat sensitive, and the fact that wastewater-based epidemiology obscures the end user of drugs is a positive asset because it’s less stigmatizing.”

Hannah says that researchers plan to discuss early findings with drug users in Marin to best understand how drug use affects their community.

“Given the environment and the fact that some of the drugs we test are illegal, I think there is a concern that law enforcement might have interest in using data for targeting certain communities,” Hannah said. “I see people who use drugs as a vital partner in overdose prevention. They’re the people on the ground who are witnessing, experiencing and preventing overdoses day to day.”

Why Is San Francisco Lagging Behind?

Like many other cities, San Francisco has recently used wastewater testing to track pathogen spread. But it has yet to implement an opioid or drug chemical tracing system in its wastewater program, despite the fact that the city remains a national hot spot for drug use and overdoses.

Epidemiologists and researchers say that some of the delays in implementing wastewater epidemiology may be attributed to a degree of healthy skepticism within the science community. But some warn that the lag in implementing this crucial research tool stems from fears about what the research will find.

“There is a risk of creating stigma for a community where drugs get detected, where levels might be higher than in neighboring communities,” Halden said. This might be true for San Francisco, a city that has become the poster child for the nation’s ongoing drug crisis, and which reported 620 fatal overdoses last year.

Yet, it’s likely that the city hasn’t implemented a wastewater detection program simply because interest in this technology really only took off on a statewide and national level during the pandemic, and many local jurisdictions have yet to catch up.

In San Francisco, both the SF Public Utilities Commission—which collects and treats the city’s wastewater—and the Department of Public Health told The Standard that they do not control what pathogens or chemicals to test for. That’s under the purview of the California Department of Public Health and WastewaterSCAN, which currently only tracks pathogens.

“The pandemic opened up opportunities for us to think about partnering outside of our silos,” Hannah said. “Public health problems are getting more and more complex, meaning we need more and more people involved who are experts in different parts of the system.”