That first bottle of pills was supposed to last Thomas Wolf a month, but he finished it in ten days. Wolf—then a city employee, husband and father of two—underwent foot surgery in 2015. The narcotics prescribed by his doctor, 10mg pills of oxycodone, did more than ease the pain.

“I felt this euphoria,” Wolf said. “Not only was the pain gone, but all my problems were gone, too.”

Wolf’s addiction spiraled. He stopped paying the bills, instead spending hundreds of dollars a day on opioids purchased illegally from “Pill Hill” in the Tenderloin. Eventually, short on cash and desperate for a fix, Wolf made the switch to heroin.

“I’d heard you could purchase a dime of heroin, which is enough to get you plenty high, for ten bucks,” he said.

Shortly after, Wolf’s wife gave him an ultimatum: go to rehab or leave the house. Not yet ready to get clean, Wolf walked out on his family. He spent the next six months living on the streets of San Francisco.

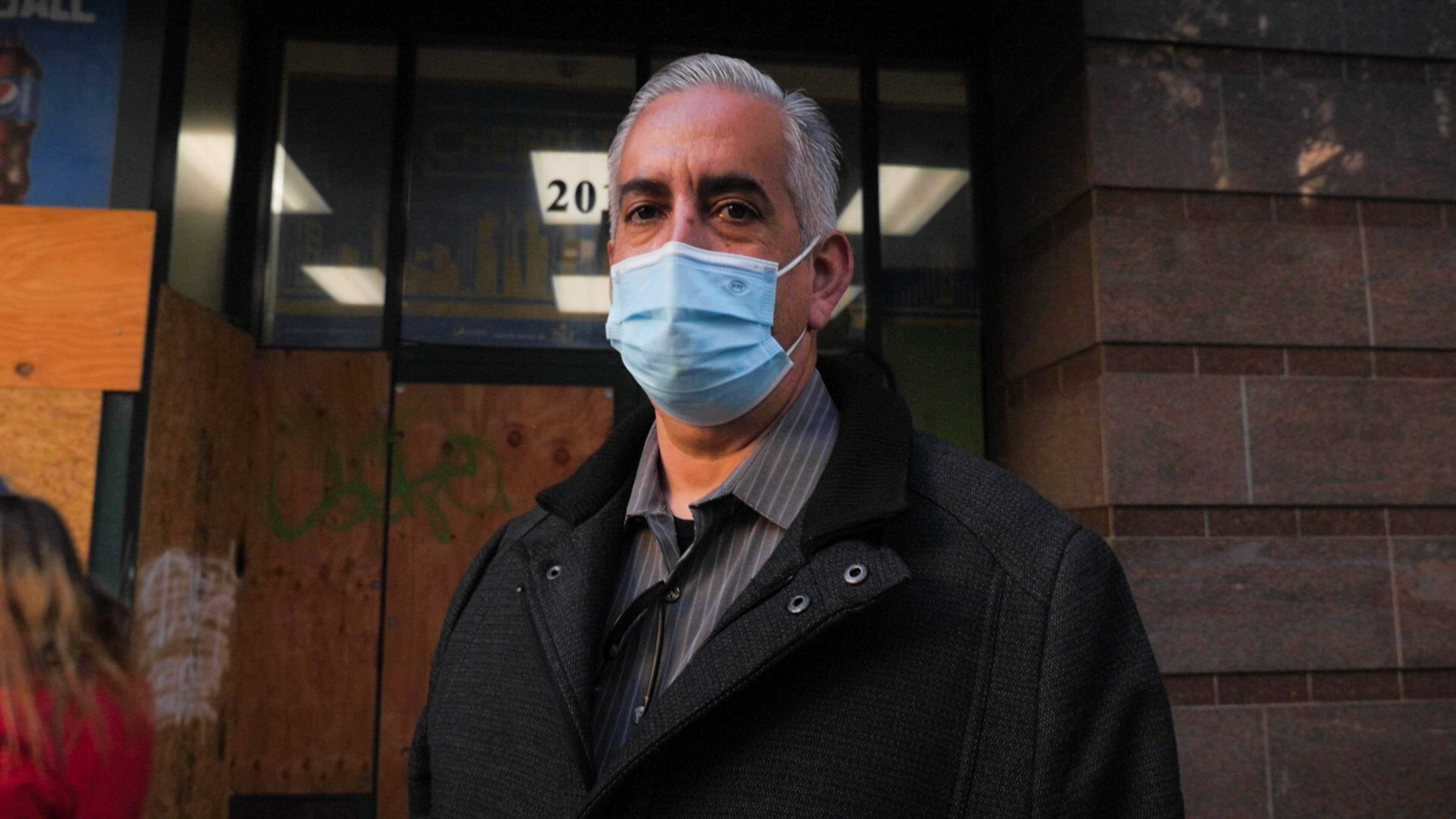

Now sober, Wolf is an outspoken advocate for treatment and recovery. He credits jail time with saving his life. The sixth time Wolf was arrested, he was held for almost three months—long enough for him to get clean and select a six-month rehab program.

San Francisco has long focused on harm reduction (opens in new tab)—making drug use safe for users. But Wolf says City Hall has the equation backward.

“The city needs to make it harder to get high and easier to get treatment,” he said. “Right now, it’s the opposite.”

While homeless, Wolf recalls being approached with a drug kit—a baggy containing items like syringes, tourniquets and cotton balls—for safe drug use. “For us users on the street, it was like ‘Bingo!’” he said. But Wolf says he was never once approached about treatment programs.

Wolf also advocates for stricter penalties for fentanyl drug dealers—fentanyl being the drug responsible for the most accidental overdoses in San Francisco, according to a preliminary data report (opens in new tab) by the city’s chief medical examiner. He’s a proponent of conservatorship (opens in new tab), too, which allows the state to compel certain individuals who can’t help themselves into mandatory treatment. San Francisco adopted a pilot program (opens in new tab) to expand court-ordered mental health treatment last year, but as of November 2020, not one person had been considered for the program (opens in new tab).

“There is a subset of people on the street that require intervention,” said Wolf. “They just do. I required intervention. If I hadn’t gotten in trouble with the law, would I still be out there on the street or dead? Yeah.”

Meanwhile, San Francisco’s drug crisis is worsening. In the first 11 months of 2020, there were 636 deaths (opens in new tab) from overdoses, up from 441 deaths in 2019 and 259 deaths in 2018.

“It’s out of control,” said Wolf.