The path to recovery from drug addiction in San Francisco is riddled with drug dealers who are allegedly selling fentanyl on the doorstep of one of the city’s largest treatment facilities.

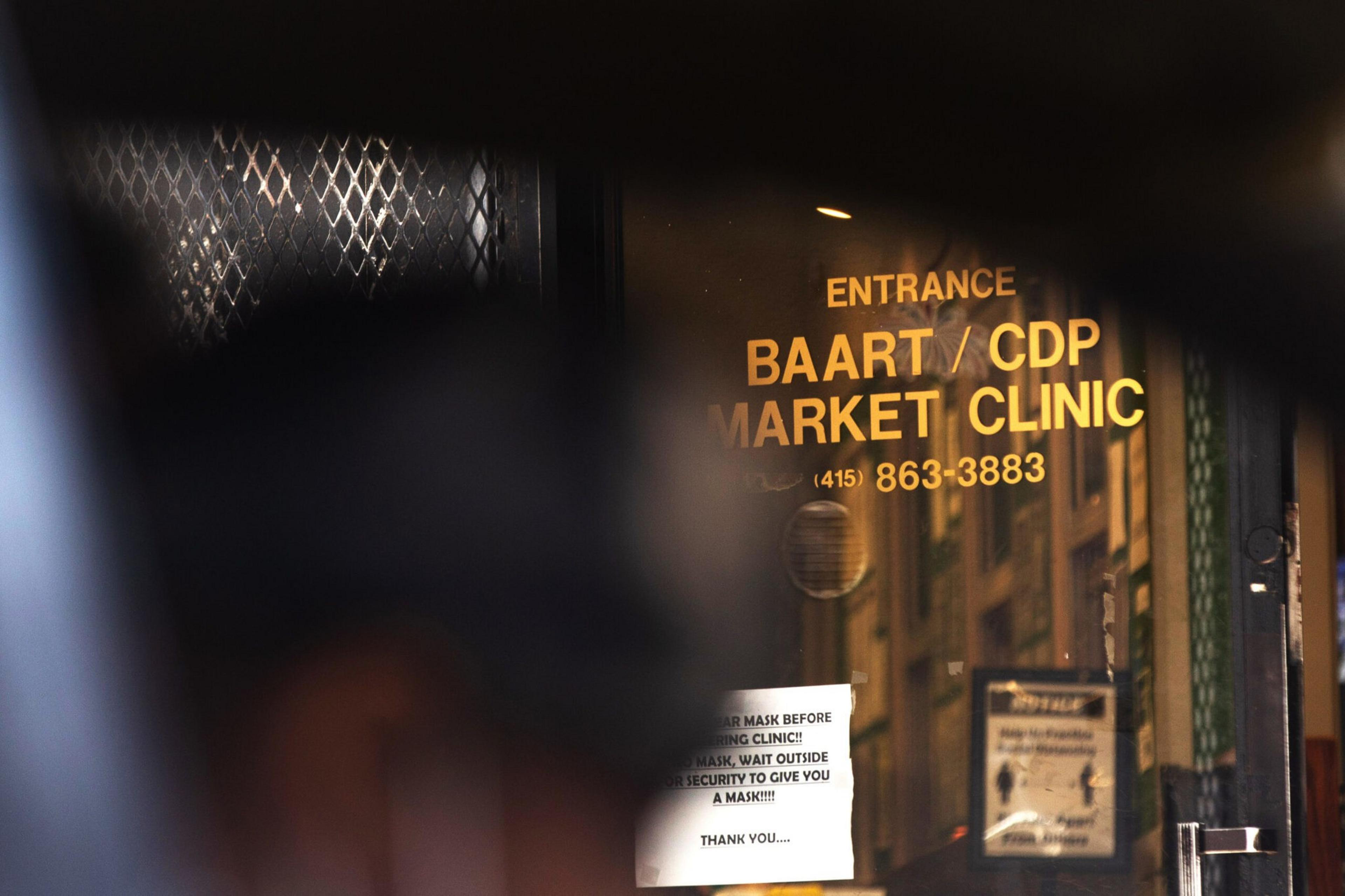

The Bay Area Addiction Research and Treatment (BAART) clinic on Seventh and Market streets, which is one of the city’s largest providers of the detox medication Methadone, is battling omnipresent drug dealing and use in front of its building, according to the clinic’s director Kris Prasad.

Prasad said that the drug activity around his facility is more triggering than ever for his clients and he fears “something egregious would have to occur” for the city to take action.

“We’re the only program in this sea of users and dealers that’s actually trying to make a difference for patients,” Prasad said. “It’s harder to come in the clinic every day than it is to just go and buy fentanyl.”

Prasad’s clinic provides addiction treatment for around 750 patients, 40% of whom are required to visit the facility daily. The remainder must visit monthly to receive their medication.

Prasad said that a daily 7 a.m. “sweep” by community ambassadors effectively pushes nighttime drug activity from Market Street into the dead-end alley where the clinic’s main entrance is located.

On Tuesday, a crowd of people gathered around the building using drugs while an unhoused man named Corey Sylvester visited the clinic to receive one of his daily doses.

Sylvester said that he had been making an effort to cut down on fentanyl by replacing it with methadone, but getting to the clinic can often be difficult for him.

“It’s hard enough to go there for me,” Sylvester said. “If people are trying to get clean, they shouldn’t even come to this city in the first place.”

Prasad added that the recent spate of bad weather has drawn people to gather under the awning of the Civic Center BART Station outside of his building.

“You’ve got people using, people defecating and dealers that are literally lined up and down that block,” Prasad said. “Our patients are having to walk through all of that.”

Prasad said that the mere presence of police in front of his building helps to alleviate the situation. But the issue multiplies when law enforcement leaves, drawing a large crowd that presents a gauntlet for his patients.

“You have to walk in a single file line to get to where you’re going,” he said. “As soon as the police come and do their sweep, [drug] traffic doubles because they assume they won’t be back.”

The city is grappling with debates over the effectiveness of prosecuting drug dealers as a response to the fentanyl crisis. Detractors of the practice argue that it’s ineffective at reducing drug deaths and punitive toward marginalized communities, while proponents say that ubiquity of the street drug supply in the city is perpetuating deadly habits for hard drug users.

The Department of Public Health said in a statement that it’s working with the Department of Emergency Management to address street conditions around the BAART clinic, but didn’t provide further detail.

Some people who were using drugs in the area pushed back against the idea that the street conditions were making it harder for them to recover from addiction.

“People either make up their minds to do something or not,” said a woman named Heaven, who was bent over in half after taking a hit of fentanyl. “You have a choice: Do you want to get methadone, or do you want to get fentanyl?”

Others, however, echoed the sentiment that San Francisco is a notoriously difficult place to follow through with treatment.

“Now that I’ve experienced the city like this I’m not sure I could live here sober,” said a woman named Carmen, who was living in a tent down the street from the BAART Clinic. “It’s not just the Tenderloin; it’s the city in general for me.”