A top Department of Public Health employee is making six figures moonlighting for a city-contracted drug rehab nonprofit that’s currently embroiled in a financial scandal and may be forced to shut down some of its programs.

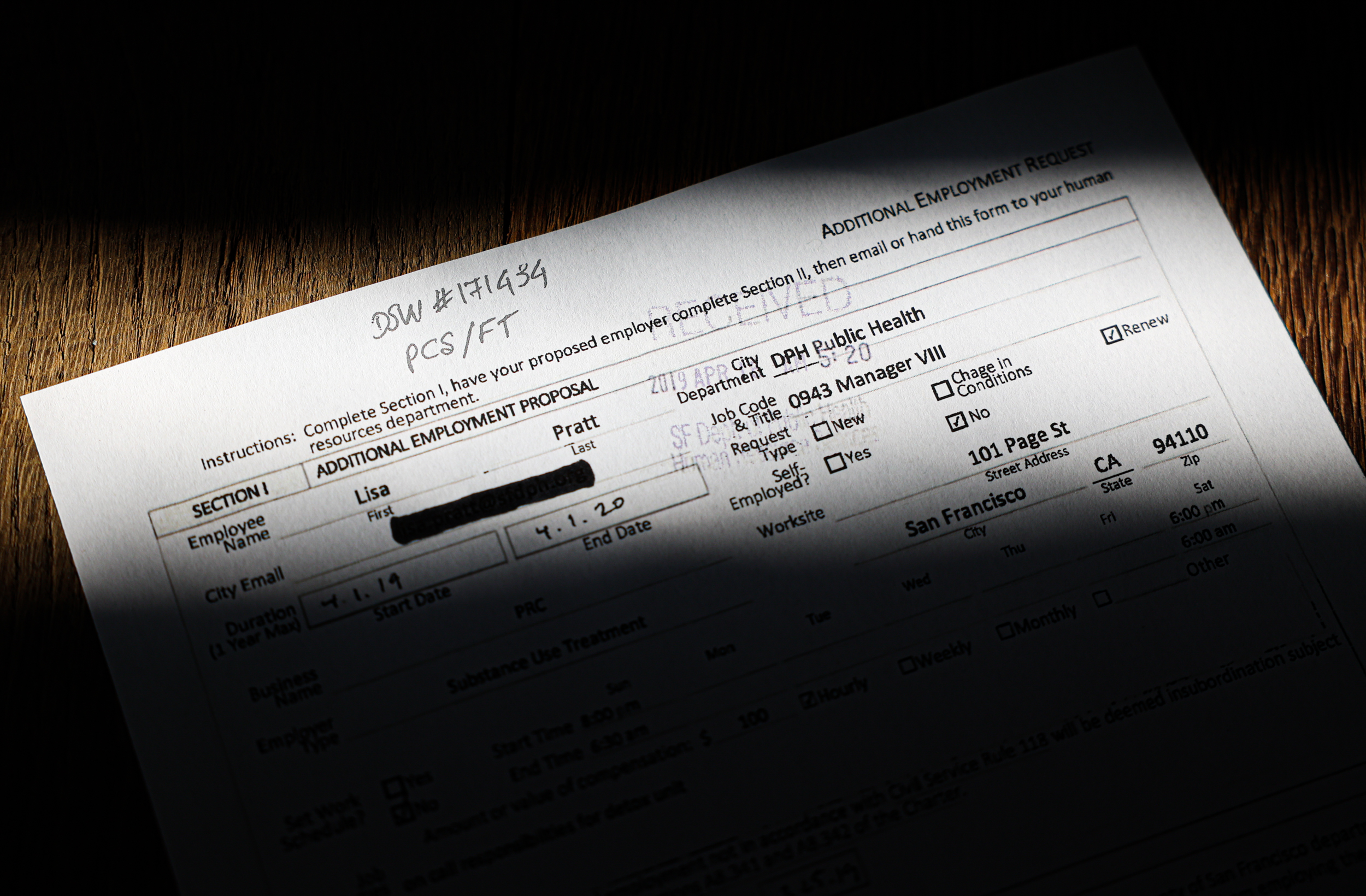

At her day job, Lisa Pratt works as the city’s director of Jail Health Services overseeing medical care for inmates. But on the side, Pratt clocks 20 hours a week as the medical director of Baker Places, earning $123,000 a year on top of her $428,750 city compensation. Baker Places receives the bulk of its funding from the health department, which also employs Pratt.

The arrangement raises ethical questions and highlights ongoing concerns about the financial management of the troubled nonprofit.

Public records show Pratt working a seemingly implausible schedule: On top of her 8-to-6 day job with the city, a secondary employment filing shows Pratt clocking in from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. on Saturdays and 8 p.m. to 6:30 am on Sundays at Baker Places, providing guidance on medical issues for Joe Healy Detox center.

Baker Places and its administrative arm, Positive Resource Center, run a major drug rehab conglomerate amounting to 215 treatment beds and close to $70 million in contract awards for this fiscal year, according to a city database. But this month, the organization reported a $4 million shortfall and threatened to close some of its programs unless the city covered the loss—a move that shocked City Hall legislators, who had bailed out the organization just months earlier.

Hearing of Pratt’s second salary, Supervisor Aaron Peskin—who was skeptical of the organization’s bailout request—was irate.

“Jail Health Services is understaffed right now. They’ve got their employees doing mandatory 12 hour shifts. It just feels really wrong if the head of that department has another half-time job,” Peskin said. “Shame on DPH for saying it’s OK.”

Pratt and the Department of Public Health defended the dual employment arrangement as lawful and consistent with city guidelines, saying that Pratt did not perform work for the nonprofit while on the clock as jail health director. According to the city’s Good Government Guide, Pratt’s side job would only present a conflict if she worked in the interest of the nonprofit on city time.

But the arrangement raises further questions about the operations of the financially troubled drug rehab organization—which reported the $4 million shortfall just three months after receiving another emergency bailout from the city—and its long-standing entanglements with local government.

“Anytime there is even a hint of impropriety then that needs to be dealt with,” said Richard Greggory Johnson III, a University of San Francisco professor who specializes in nonprofit policy. “She might not have done anything outright wrong, but it’s certainly unethical.”

In a phone call, Pratt said that her work as medical director at Baker Places amounted to being an on-call “consultant” on weekends, during which time she makes herself available for calls and “sleep[s] with her phone.” Pratt began working at Baker Places in 2000 and started working for the city in 2016; she said the obligations of the two jobs align, so it didn’t occur to her that there was an appearance of a conflict.

She told The Standard that she stops taking calls for the nonprofit once she clocks in for the city at 8 a.m., which is an hour-and-a-half after she finishes her on-call shift at Baker Places on Monday mornings.

“I haven’t gotten anything but a cost-of-living raise,” Pratt said of her six-figure, part-time position at Joe Healy Detox, one of the programs operated by Baker Places. “If I wanted to make money, I’d be an orthopedic surgeon.”

Strapped for Cash

Joe Healy Detox center is among the programs expected to close this year after an abrupt declaration of insolvency by Positive Resource Center (PRC) and Baker Places this fall.

On Oct. 3, PRC’s interim CEO Chuan Teng reported a six-month shortfall of $4,242,498 and said that unless the city covered those expenses, Baker Places would “have no other choice than to immediately notify staff of layoffs, discontinue intakes and wind-down operations.”

But there had long been signs of trouble at PRC and Baker Places, two separate but closely related nonprofits that announced a merger in 2016. Baker Places operates residential detox and other treatment programs, while PRC provides administrative support to Baker Places, among other programs.

At a June 2022 emergency hearing, Baker Places and PRC dropped a bomb: They were in serious financial trouble, and asked the Board of Supervisors for an emergency award to remain solvent. The board approved a $1.2 million emergency grant—albeit with reservations—among other efforts to keep the rehabs afloat. Those included a $1.2 million contract increase, a financial consultant hired at public expense and delayed repayment of funds owed to the city, among other actions.

One month before that June emergency hearing, the city had granted Baker Places a $65 million, five-year contract extension. More than a third of that funding went to the Joe Healy Detox center, which accrued between $750,000 and $1 million in annual debt, said former Baker Places CEO Brett Andrews at a hearing in June.

On its 2017 tax return, Baker Places reported a $1.9 million deficit a little over a year after receiving $15 million from the city as part of a multiyear contract extension.

Andrews, who reportedly quit his post shortly before Teng’s Oct. 3 letter, was earning $293,230 annually running the drug rehab programs. Andrews also served on the Our City, Our Home Oversight Committee, a panel that advises the city on how to spend money on homelessness and mental health initiatives, until June.

Asked whether the nonprofit’s financial troubles impacted its level of service, Pratt said that “she didn’t know anything” and suggested that the turmoil could be a result of the attempted merger with PRC.

Costly Divorce

After PRC and Baker Places’ $4 million bailout request on Oct. 3, the Department of Public Health moved to cut ties with the organization, writing in a response letter that it “feels strongly that it is in the best interest of our clients, the public, and the Baker/PRC for the City to find alternate care providers.”

The department said this month it plans to find new placements for Baker Places’ clients in the coming weeks—a momentous task given a citywide drug crisis and shortage of behavioral health beds. Since then, the department has declined to give updates on the details of that transition.

PRC and Baker Places’ network of rehab and behavioral health facilities include Hummingbird Place, Hummingbird Valencia, Hummingbird General Hospital and Ferguson Place. Fourteen of Baker Places’ treatment beds were operated by the Department of Public Health until 2019, when the city “redistributed” city-run beds to Hummingbird Place.

Matthew Wooldridge, a former patient at Joe Healy Detox center and three other Baker Places’ programs, said that he felt Baker Places’ administration wasn’t responsive to clients and noted that several of his peers didn’t complete their treatment, an occurrence he blamed on a lack of attention from staff.

Former employees at Baker Places described a revolving door of counselors and other frontline workers that made as little as $22.85 an hour, leading to inconsistent care among high-risk clients.

“It was 30 days you have with your ‘cellmates.’ You get prepared meals and limited TV time,” Woolridge said of his time at the Joe Healy Detox center. “The nurses were great themselves…But the administration, not so much.”

After speaking with The Standard, Peskin said he was going to immediately call the Department of Public Health’s chief financial officer about Pratt’s dual employment.

“That’s about what I get paid,” Peskin said in reference to Pratt’s six-figure weekend shift. “But I’m not allowed to sleep it.”

“You expect department heads who are getting hundreds of thousands a year to be singularly focused on that,” he continued. “This is not a janitor who’s making ends meet, holding down a second job in order to put food on the table; this feels like abusing the system.”